Having climbed the fabled carpeted steps of the Grand Théâtre Lumière three times in the past 48 hours, I have this to say: That red carpet's looking pretty damn dirty. Up close, it strongly resembles that indoor-outdoor carpeting from Lowe's, made out of some thin, hard-wearing synthetic, that your aunt and uncle installed in the rec room.

This might be a metaphor for something, or might not. Either way, this year's collection of Cannes films, which looked so alluring from across the sea, is almost uniformly dark to this point. Even given international art cinema's propensity for self-seriousness, Cannes at the halfway point has been a festival of pointless killings, innocents unfairly persecuted, investigations that go nowhere and sex scenes crafted for maximum discomfort and minimum arousal. And then there are the movies!

That was a joke. I am talking about the movies. But the contrast between the dire, dour, downer cinema on display and the louche, idyllic surroundings here is -- well, "ironic" doesn't come close. It's utterly bizarre is what it is. Sunday night I sat through Austrian director Ulrich Seidl's "Import Export," a docudrama in competition here that offers two and a half hours of squalor tourism through the most horrible spots of central and eastern Europe. We visit an Internet-porn production facility in Ukraine, where women writhe in rows of cubicles for online customers; an unbelievably filthy housing complex in Slovakia, whose residents simply dump garbage behind the buildings in huge piles; a geriatric hospital in Vienna, Austria, full of toothless and delirious dying patients. At least in the dive bar where you can recruit a hooker to get naked and crawl around on a leash for 50 euros, it appeared that people had recently eaten, and you could see the floor.

Then it was back out into the night for a salade niçoise, made right in front of me with fresh tuna and crisp green beans. Yum! And, gee, it's true what they say here about this year's new rosé, isn't it? And now let's move on to the Brangelina news.

Actually, I just saw Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, looking restrained and sober in a tan suit and brown knee-length dress (respectively), on their way out of the press conference for "A Mighty Heart," in which Jolie stars and which Pitt helped produce. They'll stroll up that dirty red carpet on Monday night, and Pitt will return on Thursday with Steven Soderbergh's "Ocean's Thirteen." (Both films are premiering out of competition.) Star power aside, "A Mighty Heart" isn't exactly a rousing up-with-people movie either, given that Jolie plays Mariane Pearl, whose husband, Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl (played by Dan Futterman), was kidnapped and beheaded by Islamic fundamentalists in Pakistan. (Mariane Pearl has written for Salon.)

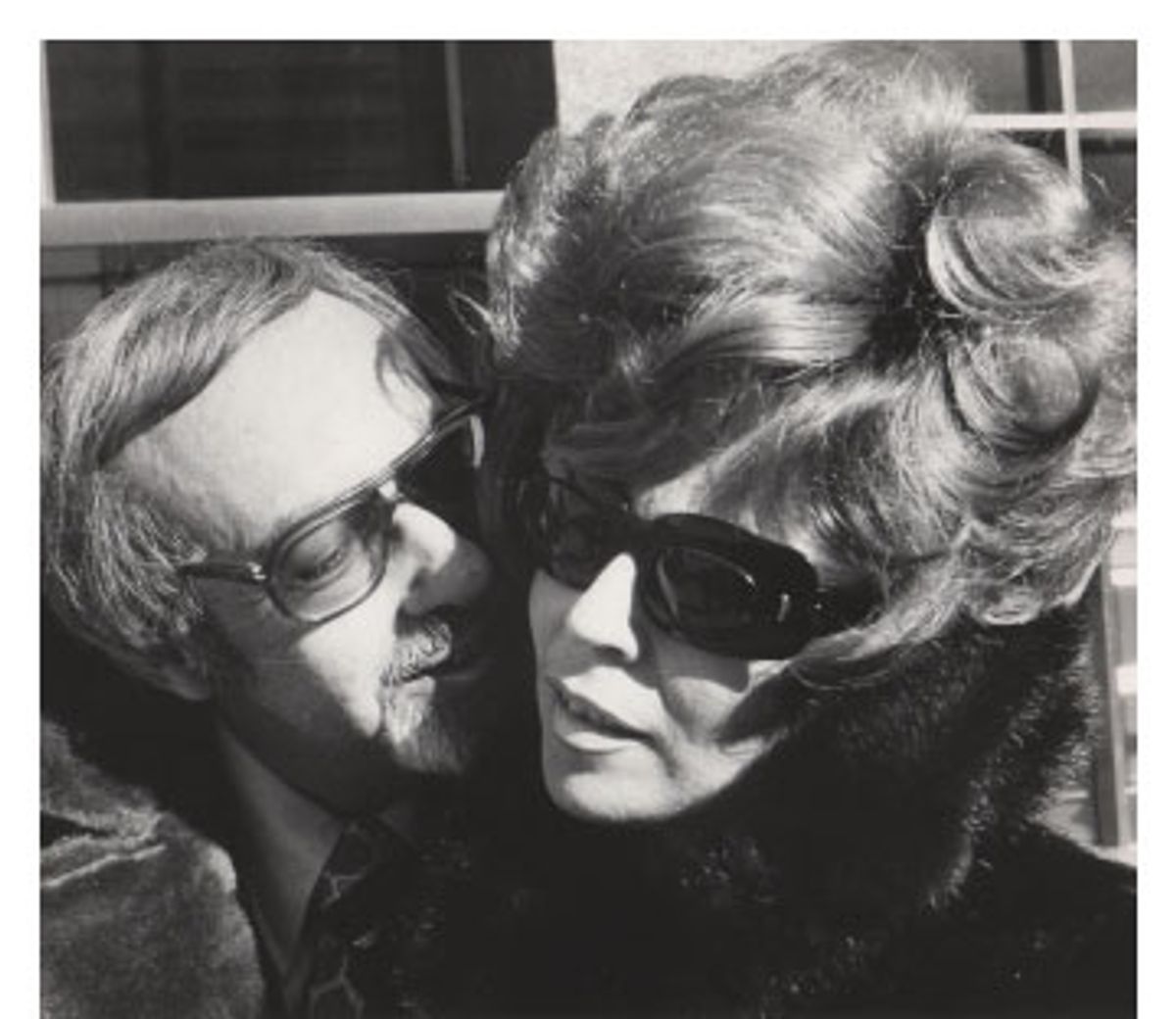

"A Mighty Heart" will open worldwide next month, and I'll leave the heavy-lifting review duties to my colleague Stephanie Zacharek. Suffice it to say that this film is bound to provoke some controversy, although for the most part it plays like a straightforward, highly competent thriller. As you'd expect from English director Michael Winterbottom, the picture possesses levels of moral complication that are at first invisible; it feels like an extra-long episode of "24" with a bad conscience and a bad ending. Jolie's performance is restrained and dignified, and with her hair in Mediterranean curls, she actually bears a strong resemblance to Pearl, a Parisian woman of mixed racial heritage. (Winterbottom has observed that trying to find an actress who was half Dutch, a quarter Cuban and a quarter Chinese was not realistic.)

But Mariane Pearl is not really at the center of Winterbottom's film, even though it was adapted from her memoir. What Pearl principally does in the story, after all, is sit around the Karachi villa of her friend Asra Nomani (played by Archie Panjabi in the film, Nomani is an American journalist of Indian heritage who has reported for Salon and other publications), waiting for her worst fears about what has happened to her husband to be fulfilled. So for both dramatic and philosophical reasons, John Orloff's script moves back and forth between Mariane's private agony and the murkier, larger story of Pakistani and American authorities' hunt for Daniel Pearl's kidnappers.

There are viewers -- American and otherwise, right wing and otherwise -- who will really hate "A Mighty Heart" for its perceived politics. Without remotely excusing the heinous crime committed by Daniel Pearl's kidnappers, Winterbottom and Orloff place it in context, specifically the shadowy context of Pakistan in 2002. In this telling, American diplomats watched as Pakistani security forces used, um, "harsh tactics" on people swept up in the Pearl investigation, some of whom were involved and some weren't.

In fact, Pearl's kidnappers were demanding the release of Guantánamo Bay detainees, and we can only watch ruefully as Colin Powell assures TV cameras that the prisoners in Cuba are being treated humanely and respectfully. Of course the U.S. government was not going to accede to those demands, nor should it have. But in an odd sense "A Mighty Heart" is a companion piece to Winterbottom's "Road to Guantánamo." As Mariane Pearl herself told a CNN interviewer after her husband's death, 10 other people had been murdered by terrorists in Pakistan during the same month (and none of them were foreigners). Every personal tragedy that captures our attention is a subset of a larger, more communal or global tragedy.

In addition to "A Mighty Heart," I've seen three other movies at Cannes that feature unsolved crimes and/or fruitless investigations. I don't know if this collective loss of faith in authority results from the Bush administration's Iraqi WMD hunt or some existential angst that's more atmospheric in nature, but it's striking. Most prominent of these is "No Country for Old Men," the latest sojourn into comedy-inflected noir (or noir-inflected comedy) from Joel and Ethan Coen, aging enfants terribles of the Amerindie scene.

If there's a favorite for the Palme d'Or among the competition films shown so far, it's probably the Coens' adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's novel (second place, by a nose, goes to "4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days," a wrenching film about abortion in Ceausescu-era Romania). It's the most ambitious and impressive Coen film in at least a decade, featuring the flat, sun-blasted landscapes of west Texas -- spectacularly shot by cinematographer Roger Deakins -- and an eerily memorable performance by Javier Bardem, in a Ringo Starr haircut, as a Terminator-esque hit man with a cattle-killing air gun.

There are some superficial similarities between "No Country for Old Men" and both "Fargo" and "Blood Simple," and it has been widely assumed that this film is in some sense a return to the Coens' roots as genre-film enthusiasts. Yes and no, but mostly no. For the first hour or so, all the elements of a classic crime-chase picture are in place. A likable, trailer-dwellin' good ol' boy named Llewellyn (Josh Brolin) stumbles across a whole bunch of dead drug dealers and a suitcase of money in the desert. Once he takes the money, of course, a grand fatalistic plot is set in motion, with both the decent, aging sheriff (Tommy Lee Jones) and the sinister Anton Chigurh (Bardem) on his trail.

Readers of McCarthy's novel will not be surprised, of course, that conventional thriller expectations are defeated at almost every turn. Key plot developments are unexplained, characters' destinies remain incomplete, and several key events occur off-screen. (This film won't open in the United States until November, so I'm trying not to be too specific.) With this outstanding cast -- Jones is at his best, and Brolin is a revelation -- and impressively bleak photography, "No Country for Old Men" has the potential to be a breakout hit. On the other hand, American audiences are not known for tolerating genre thrillers that decompose, '70s style, into existential anomie. My gut feeling is that this ambitious experiment doesn't entirely work.

Still, every Coen film is tricky, and this one more than most; I want to see it again before reaching a final conclusion. I'm afraid that Gus Van Sant's "Paranoid Park" -- yet another film revolving around an unsolved crime -- is precisely what it appears to be on the surface, a visually lovely, semi-experimental riff on Dostoevski's "Crime and Punishment" that has almost no point of contact with actual human existence. (It premieres here late on Monday night.)

Van Sant's recent films (like "Elephant" and "Last Days") have trended toward visual and auditory sculpture and that's again true here, even though "Paranoid Park" has actors and lines and all that. (The actors were recruited on MySpace -- really! -- and the dialogue is minimal and deliberately repetitious.) Adapting Blake Nelson's young-adult novel about Alex (Gabe Nevins), a teenager plagued with guilt over a security guard's death near a skateboard park, Van Sant turns the story into a concatenation of echoing and repeating elements, skipping unpredictably backward and forward as Alex gradually tries to make sense of what has happened.

This is another film with great cinematography (it's by Christopher Doyle, who shot many of Wong Kar-wai's early movies), and Van Sant has always captured the rainy, temperate, urban-but-rural surroundings of Portland, Ore., as moody visual poetry. But his highly aestheticized and stylized depictions of teenage life sometimes seem as if they were shot through the wrong end of a telescope. Van Sant wants his brief, deadpan, underpopulated scenes -- some of them shot on 8 mm video, others with overlaid music so we don't hear the dialogue -- to feel more like real teen existence than the clichés of mainstream cinema. It's a worthy goal, but I'm afraid the actual effect is the opposite. How did these sweet kids get trapped in a middle-aged art film, and how can we get them out?

* * * * For more coverage of the Cannes Film Festival, click here.

Shares