In the world of fine dining, few chefs rise to the heights that Jasper White achieved in the '80s and '90s with his eponymous Boston restaurant Jasper's. Lauded in the press, awarded numerous stars and accolades (including a James Beard Award), Jasper's even touted Julia Child as a regular customer (she called White her "all-time favorite Boston chef"). Even fewer chefs, though, would take a successful enterprise like this and shut it down to devote oneself to comfort food. Yet that's exactly what White did in 1995 when he closed Jasper's, spent five years writing cookbooks, and then, in 2000, opened Summer Shack, a family-friendly seafood spot devoted to all-American shore food -- the kind you don't serve on white tablecloths.

Now four restaurants strong (with locations in Boston, Cambridge and at Mohegan Sun and Logan Airport), Summer Shack is a mini restaurant empire with White at the helm. Gourmet magazine says it serves "the best lobsters and corn dogs in the land," and it got three stars from the Boston Globe. White, it would seem, can't run away from success, no matter how hard he tries.

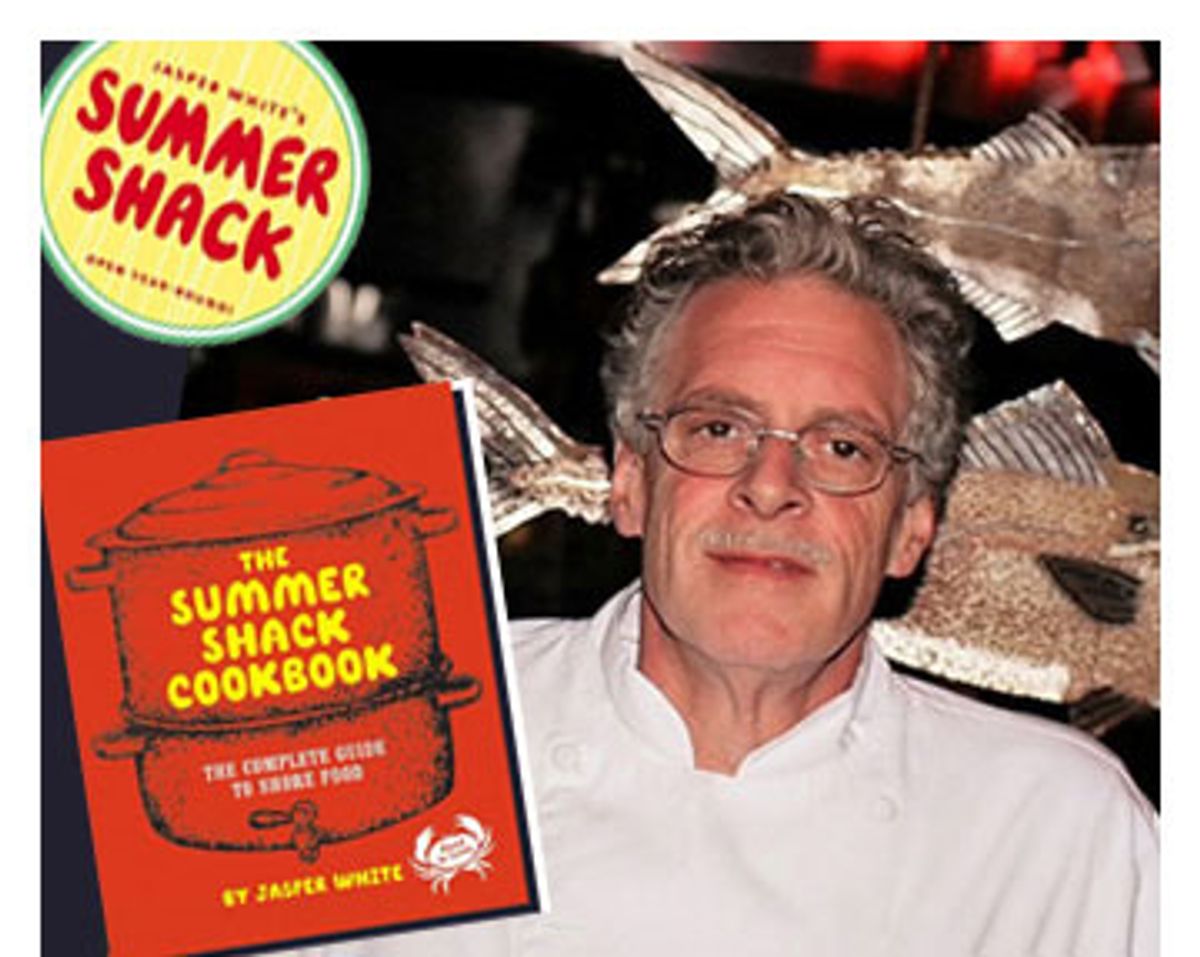

"The Summer Shack Cookbook" is White's effort to parlay that into book form. The book is so authentic, you half-expect sand to come pouring out of the pages as you flip through them. Between bright red covers with yellow lettering that sings of summer and lobsters and Maine, White offers instructions on every salt-watery subject from shucking oysters to picking mussels. Nifty graphics illustrate the precise way to cut up a chicken, how to filet a fish, and -- perhaps most important -- the proper way to eat a lobster.

Summer Shack's motto (which White has trademarked) is: "Food is love." If you type his name into Google, the fifth result is a link to a Julia Child video of White teaching Child how to make chowder, fish stock and roasted lobster. White is all downcast concentration and Child is all cheerful enthusiasm; they come across like a slightly less intergenerational version of "Harold and Maude." But what's abundantly clear is how passionate White is about what he's cooking and how delighted Child is to be at his side. With Summer Shack and "The Summer Shack Cookbook," White honors Child's legacy of bringing quality food to the masses and teaching people how to eat well.

Congratulations on the book. At what point did you decide to write it?

It seems like I'm always writing a book. They take me a long time. This is my fourth book and my first book came out in 1989. It was called "Cooking for New England" (it's still in print). Since then I've always had a book going and when Summer Shack opened I started thinking about it in terms of a cookbook. About two years into it I started for real: writing the book and doing the recipes, testing the recipes. It took me five years from start to finish to get this book done.

Is it difficult translating restaurant recipes into recipes for the home cook?

It isn't really. I've been at it a long time. I once did a Thanksgiving piece many years ago, back in 1984, with Craig Claiborne (the writer for the New York Times). I went to Long Island and spent three days with Craig. We cooked all these different dishes and he was the most fastidious recipe writer I had ever seen in my life. He taught me how people really depend on recipes and that you have an obligation to make it right because when people buy your book or buy your newspaper, they're expecting the works. I've always taken that approach and that's why it takes me so long to write these books: I don't fake them. I actually write them myself.

What's nice about this book, in particular, is the detail. Like the diagram for how to eat a lobster.

Lots of people wouldn't admit it, but they don't know how. They really don't! It's kind of like Thanksgiving recipes for turkey. You'll have a five-page recipe, or whatever, and at the end of the recipe it says, "Carve the turkey." You know what? Guess what? That's the part people don't know how to do. There's nothing easier than steaming a lobster, but it really helps to know how to eat it.

Why do you say, as you do in your book, that it's better to steam a lobster than to cook it in tap water?

I stand by that for a couple of reasons. One is that if you use tap water to boil lobsters it just dilutes the flavor if the water gets into the lobster. The other thing is that boiling in general is a pretty tough technique for people. Steaming is a slower cooking process and it cooks lobsters more gently and they come out more tender.

I saw an episode of Julia Child with you as her guest (it's on the Internet) where you roasted a lobster. Is that something you recommend trying?

I definitely do. My standard line with lobsters when people say, "What's the best way to cook it?" is: "How often do you eat it?" If you eat lobster three times a year, the only way to eat them is plain. So you get all the little nuances, the different textures of the different parts of the lobster: It's a real treat. That said, the lobster is as versatile as chicken is. They can be roasted, they can be baked, they can be cooked in a wok, they can be sautéed; in terms of technique, there's versatility, and in terms of flavors that lobsters go with, it can go with Mediterranean flavors, American flavors -- like corn -- Caribbean and South American flavors.

For somebody who doesn't live near the water who has to buy their lobster from a tank, how do you know what to look for?

One of the sure ways to tell is if you look at the antennas. When lobsters are in captivity, the bands keep them from ripping each other to shreds but they still have ways to get each other's antennas. So if you look at a lobster and its antennas are about an inch long, that means they've been in that tank a long time. And that definitely affects the integrity of the lobster. Liveliness is a good sign but that can fool you too because the lobsters do pretty well in those tanks. You can look at the condition of the tank: Is it really murky? The other thing that people need to understand is that for a little extra they can have lobsters shipped directly to them. There's a Web site called the Maine Lobster Promotional Council and they have over 100 vendors there that'll ship.

Let's talk about your career. You opened Summer Shack after closing Jasper's. How did that transition come about?

I've been cooking for 35 years now. I learned my craft and my trade in the early '70s and it was mostly classical French cuisine; that's what I was trained to do. I have a deep love for it and I also have a real appreciation for those techniques. But after 25 years of fine dining, and doing Jasper's for 12 years -- I'd touched 90 percent or 95 percent of the dishes that went out. In 1994, the year before I closed Jasper's, I was nominated for a James Beard Chef of the Year, which is pretty much the highest honor you can get as a chef. I didn't win that year -- Daniel [Boulud] did -- but I was deeply honored by it. I also felt like: OK, I've done what I can do with fine dining.

And also, at that point of my life, I had small children and I was living in the city with my wife, and we bought a little cottage up in Maine to get away in the summer. There, we'd never even go to restaurants; we'd go to clam shacks and roadside stands. And I started to really yearn for the simple foods.

What was the reaction from your peers in the fine dining world?

They thought I was crazy; not so much my peers, more my customers. They just didn't understand it. They felt like I demoted myself. But over the last seven years I've built a company that's got four restaurants, I own a fish company, and we gross over $20 million a year. It's been a great challenge for me, and every night I look out there and I see people, I see families, all different kinds of people that I didn't serve before. I have a huge Asian clientele, in Cambridge I have a really good size black working-class clientele, and I'm pretty delighted to be cooking for lots of different types of people.

Do you ever miss having a fine dining restaurant?

I do, and I might do it again sometime. I never say never, but I don't yearn for it. I like the challenge of running these restaurants and having such a large crew and serving so many people.

Was it hard to drop your old habits of perfecting things on a plate the way you do in fine dining?

That gets to me sometimes. But my deal now, I think I even say it in my book -- with simple food, looks are cumulative. It doesn't matter what one dish looks like, it matters what a table looks like. Have lots of dishes out on a table; you don't need to make any one of them fancy.

Do you think other chefs will do what you did and open more casual restaurants?

I think almost everybody, to a certain extent, has looked at doing something more casual. Because fine dining becomes more and more difficult in terms of the profitability, and a lot of the chefs of my generation, they're all kind of getting up there and we don't have retirement plans.

It seems, though, that you've done it with integrity. Lots of chefs are quicker to sell their products or to go on the Food Network.

Even though I've made some allusions about making money, it's never been my goal. My goal has always been to keep people happy and serve really good food. When I was doing fine dining, I always felt for the prices I was charging and what that experience was about, I felt like I owed them something, that I had to be really responsible for the food. Jasper's was very personalized. It was about my name on board, they were coming to get my food, and I tried to be there as much as I could to make that food for them.

With Summer Shack it's different. It's not just my food; a lot of it is classic food. I don't feel like I have to touch every plate.

In your book, you advocate eating locally. Do you think with all the coverage local food is getting -- a Time magazine cover story, for example -- that the trend is to move in that direction?"

In the past 20 years, on one hand, food has gotten much better in terms of variety of ingredients; and on the other hand, it's gotten much worse. There's more junk out there than ever. More convenience store crap than ever. More kids with diabetes. I feel like there's two things happening at the same time. I see people supporting local farms and farmer's markets are getting more popular than ever. I also think agribusiness is not slowing down. More agribusinesses are taking over organics now, and they're going to keep doing what they do. So there'll always be a pull between agribusiness and real farming, or small-scale farming.

What about the fishing industry? There was an article that said in 50 years there won't be any fish left.

I definitely have great concern about it. That's a complicated subject. My gut is there's something wrong with saying that in 50 years there won't be any fish left because if there's feed in the ocean, something's going to eat it, something's going to grow. Will we be eating all the same species in 50 years? No. But the good news is: I don't know of many things that grow in the ocean that don't taste good. You just gotta know how to cook 'em.

I wanted to ask you one more thing: I know you were friends with Julia Child. How did you meet?

She lived here in Cambridge and she was a regular customer at Jasper's. She was kind of a mentor for me. I used to say to my cooks, after she came in the first time, "Set up your stations and be ready because on any given night, Julia Child might walk into this restaurant." And I think to a certain extent every chef in Boston felt that way. And if you cook like you're cooking for Julia every night -- I think she improved food in the whole city.

Shares