NBC's hit series "Heroes" was the most-watched new show on network television this year despite its demanding plot lines and stretches of subtitled Japanese. Its season finale, which aired May 21, dominated the 9 p.m. time slot. What explains the show's popularity, especially with younger viewers? I think it is that, like the Fox thriller "24," "Heroes" is a response to Sept. 11 and the rise of international terrorism. But while "24" skews to the right politically, "Heroes" seems like a left-wing response to those events. In fact, it functions as a thoughtful critique of Vice President Dick Cheney's doctrine on counterterrorism.

In Bush and Cheney's "war on terror," the evildoers are external and are clearly discernible. In "Heroes," each person agonizes over the evil within, a point of view more common on the political left than on the right. Each of the flawed characters is capable of both nobility and iniquity. In Bush's vision, the main threat remains rival states (Saddam's Iraq, Ahmadinejad's Iran). States are absent from "Heroes," as though irrelevant. "Heroes" makes terrorism a universal and psychological issue rather than one attached to a clash of civilizations or to a particular race.

In its commentary on terror, "Heroes" thus avoids the caffeinated Islamophobia of "24." And at a time when "24," a favorite of older Republicans, is fading in the ratings, "Heroes" may also be a better guide to where the thinking of the young, post-Bush generation is heading when it comes to terror. It's certainly where their eyes are going. NBC's "Heroes" runs opposite Fox's "24" on Monday nights and snags a higher total of younger viewers, while the median age of "24" viewers keeps rising. As "Heroes" star Adrian Pasdar, who plays politician Nathan Petrelli, explained in an interview before this season's finale, "On Monday nights we own the demographics." He was referring to winning the ratings battle among the all-important 18-49 age group that advertisers love.

"Heroes" posits a world in which a small number of persons have been born with extraordinary powers drawn from the standard science fiction repertory. The powers include levitating objects, mind reading, flying, miraculous healing, bursting into flames and, as with the painter Isaac Mendez (Santiago Cabrera), prophesying the future. The plot that drives the first season has to do with a prophetic painting by Mendez that shows New York City being blown up. The bomb is not mechanical but is a human being, a mutant, who cannot control his powers and will ultimately explode in the midst of the city if not stopped. For much of the season the mutants do not know exactly who will explode or when, but they know it will happen unless they prevent it.

The prospect of a walking bomb blowing up New York sets in motion at least three distinct reactions. The first, spearheaded by the middle-aged Noah Bennet (Jack Coleman) of Odessa, Texas, aims at mobilizing the mutants to become the "Heroes" of the show's title and stop the explosion. A second effort is that of a Japanese computer programmer who daydreams of being a samurai warrior. Hiro Nakamura (Masi Oka) can sometimes bend space and time, depending on his strength of will, and has seen the destruction of New York during a journey to the future. He is accompanied on his quest to save New York by his friend Ando Masahashi (James Kyson Lee).

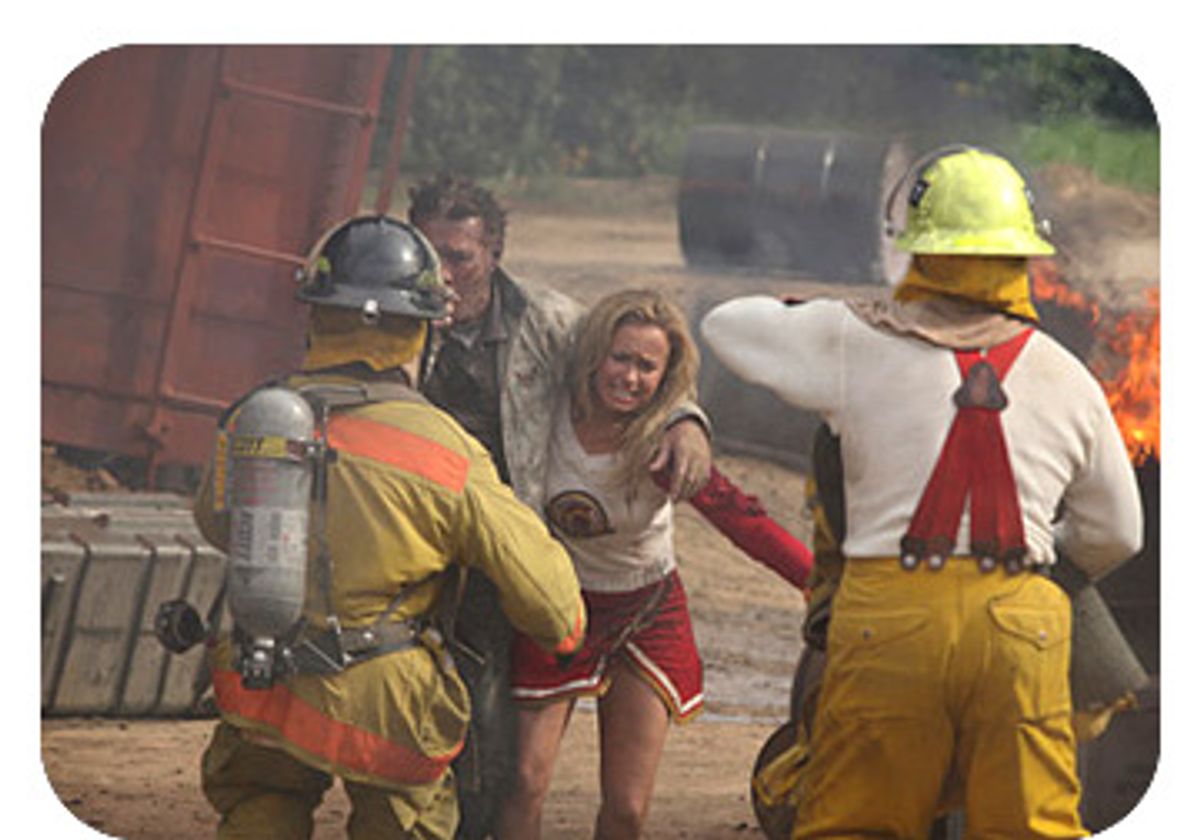

Dogging the "Heroes" is evil mutant and serial killer Sylar. He wants to kill Noah Bennet's adopted daughter, the otherwise virtually indestructible cheerleader Claire (Hayden Panettiere). For reasons that are too complicated to explain quickly, her survival is key to thwarting the explosion (hence the slogan, "Save the cheerleader, save the world.")

Meanwhile, a third camp of wealthy and powerful figures, clearly on the political right, decide that the explosion cannot be avoided and must therefore be exploited to instill new spine and discipline into the soft American public. This clique, led by a Las Vegas mobster named Linderman (Malcolm McDowell), includes Angela Petrelli, the mother of Nathan and Peter Petrelli, both mutants. The Linderman faction strives to put Nathan Petrelli into office as a New York congressman by rigging the election, convinced that he will be in a position to lead America as a strong man after Gotham's immolation.

Some bloggers have detected overtones of Sept. 11 conspiracy theorizing in this plot element. A fringe among the American public has become convinced that the Bush administration either knew about the Sept. 11 attacks beforehand and deliberately declined to stop them because it saw a political opportunity to regiment the country in the aftermath -- or that it actively conspired to bring down the twin towers.

The plot of "Heroes," however, does not really echo these conspiracy theories. Though the right-wingers on "Heroes" do use fear to their political advantage, there is little indication that Linderman and Mrs. Petrelli are involved in a plot to blow New York up or even actively desire that outcome, and they in any case are not the U.S. government. They seem simply to be convinced that the prophesied event is unpreventable and that the best should be made of it. As they define "the best," it is positioning Nathan Petrelli to play populist politics, perhaps of the Mussolini sort. (Admittedly, in the last episode this season, Claire Bennet accuses Angela Petrelli of interfering with attempts to forestall the explosion, but this motif remains ambiguous).

I think it is more helpful to see "Heroes" as a broader philosophical critique of the Bush and Cheney approach to the war on terror. The Bush administration sees the world as polarized between white hats and black turbans. Convinced that terrorist groups are gunning for the United States, and that another major attack will be hard to avoid, Bush and Cheney have responded in two ways.

At home, they have taken away key American civil liberties and created a more authoritarian society. Bush spokesman Ari Fleischer famously said after Sept. 11 and the firing of (insufficiently nationalist) comedian Bill Maher by ABC that such controversies are "reminders to all Americans that they need to watch what they say, watch what they do. This is not a time for remarks like that; there never is." That astonishing pronouncement presaged the gutting of key constitutional liberties in Bush's misnamed Patriot Act.

Abroad, the administration has imposed Cheney's "1 percent doctrine," which, according to journalist Ron Suskind, holds that if there is even a 1 percent chance that terrorists will, for instance, acquire nuclear weapons, then the U.S. government must act as though it is a certainty. This doctrine underpinned the invasion and occupation of Iraq, which turned out to be free of both WMDs and a nuclear weapons program. Bush and Cheney unleashed a rogue's gallery of Torquemadas, mercenaries, kidnappers and hit men against their enemies, throwing the rule of law to the winds and hatching such scandals as Abu Ghraib. Salon's Gary Kamiya called this doctrine a "license to lie."

The program "24," which debuted just two months after 9/11, seems to endorse that worldview. On "24," "good guys" quite often need to do bad things. Jack Bauer, the hero of the show, tortures terrorists for information and was lauded for it from the stage during the recent Republican presidential debate.

The creator of "Heroes," Tim Kring, has rejected this black-and-white, "24"-style worldview in favor of something very different. In fact, as he told comics blogger Jonah Weiland in an interview, he had initially planned to have a Middle Eastern character as the terrorist threat but dropped that scenario. His terrorist threat is murky and various, his world multicultural and morally ambiguous.

His heroes aren't even white hats. Unlike most classic comic-book superheroes, NBC's "Heroes" cannot control their powers. Many of them have Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde aspects. They sometimes do harm, whether unintentionally or deliberately. Niki Sanders (played by Ali Larter), for instance, is a Las Vegas webcam stripper who, under stress, is taken over by an alter ego named Jessica who commits bloody mayhem. Ted Sprague (Matthew John Armstrong) is radioactive and unintentionally gives his wife cancer, but he also consciously threatens to go thermonuclear.

The powers of the heroes and their unpredictable consequences function as an allegory for the asymmetric threats generated by contemporary technology. They reflect the anxieties of an era when Timothy McVeigh can use some farm fertilizer to blow up the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, when Internet hackers threaten to open the sluices of the Hoover Dam, when the cultists of Aum Shinrikyo can poison hundreds on the Tokyo subway with homemade sarin gas, and when a handful of expatriate Arab engineers based in Germany can turn jetliners into flying bombs. Technology is advancing with such rapidity that it is making each individual far more powerful than in the past and bestowing on each individual new capacities that surely not all will deal with responsibly. This passing of a technological threshold, in which a handful of terrorists with a suitcase bomb could potentially destroy a city, will be a particular burden for younger Americans, the kind who prefer "Heroes" to "24," since it will help define the future.

"Heroes" also acknowledges the subjectivity of any discussion of "terror." The show's moral vision is far too nuanced to give aid and comfort to American nationalists. The serial killer in the cast, Sylar, played by Zachary Quinto, is the closest thing "Heroes" has to a pure villain. He seeks out and removes the brains of the other mutants. In the season finale, when it is clear that Peter Petrelli (Milo Ventimiglia) is the mutant who is in danger of losing control of himself and destroying New York, even Sylar's wickedness becomes ambiguous. Sylar, in a position to rub out Petrelli before the latter explodes, realizes that were he to destroy the time-bomb mutant, he would turn out to be the true hero. He wants to kill Petrelli and save New York, but for the wrong reasons.

What happens next is an implicit argument against Cheney's 1 percent doctrine. Just before Sylar can make himself into a perverse sort of hero by killing Peter Petrelli, Hiro Nakamura runs Sylar through with his samurai sword. Nakamura saves Petrelli, but New York remains endangered. Likewise, cheerleader Claire Bennet is in a position to shoot the human bomb (who once saved her from Sylar) and so to prevent the blast, and Peter Petrelli himself, fearing his own power, implores her to do so. She does not take the shot. Both of these plot twists could be seen as decisive rejections of deploying evil to forestall disaster, and of Cheney's impoverished view of human nature.

Ultimately, Peter's brother, Nathan the politician, who can fly, swoops down and grabs Peter. Instead of following through on a scheme hatched by his mother and Mr. Linderman to have him emerge as a soft dictator in the aftermath of the apocalyptic conflagration, Nathan ascends with Peter into the heavens. The explosion lights up the night sky above New York harmlessly. Tim Kring, who has spoken of wanting a redemptive ending to the season's story line, is apparently conveying the Gandhian message that compassion and brotherly self-sacrifice are more effective in preventing terrorism than naked ambition and hard-line tactics.

Of the three elements of storytelling -- plot, character and setting -- science fiction emphasizes setting far more than most fiction. And in this genre, setting is pregnant with clues for the significance of the story. The setting of "Heroes" is global. Characters are drawn not only from small-town and urban America, but from Tokyo's manga (adult comic books) subculture and from Calcutta's community of biologists. Leading authors in the cyberpunk genre of science fiction such as William Gibson in his best-selling 1996 novel, "Idoru" (centered on a virtual reality Japanese pop star) had already pointed to the salience of Japan for American youth culture. Amitav Ghosh's "Calcutta Chromosome" (1997), a thriller about the emergence of a DNA sequence that can shift parts of a personality from one individual to another, had signaled India's new technological chic.

But these settings are more than mere homage to themes of globalization in cyberpunk science fiction. The international cast also likely stands proxy for the increasing technological savvy of the rest of the world, for good or ill, creating new challenges for a United States that is no longer a combination of isolated island and impregnable fortress. An older generation of Americans may associate the global South with backwardness, but younger viewers (and the screenwriters who dream for them) recognize that sophisticated computer viruses are invented in the Philippines and genetically engineered crops are likely to come from "Genome Valley" near Hyderabad, India.

Rather than respond with jingoism, however, the globalized vision of "Heroes" sees Japanese and Indian characters as potential saviors. Kring said in his interview with Weiland, "Again, it was part of the theme to try and depict people from different parts of the world in positive ways." Rejecting the "America-first" unilateralism of Bush, "Heroes" firmly chooses multilateral efforts in the fight against terror and refuses to give up on any character or culture as beyond redemption.

Shares