Let's say that one bright afternoon a few weeks ago you decided, as one does, "Hey, let me pop into the adult bookstore."

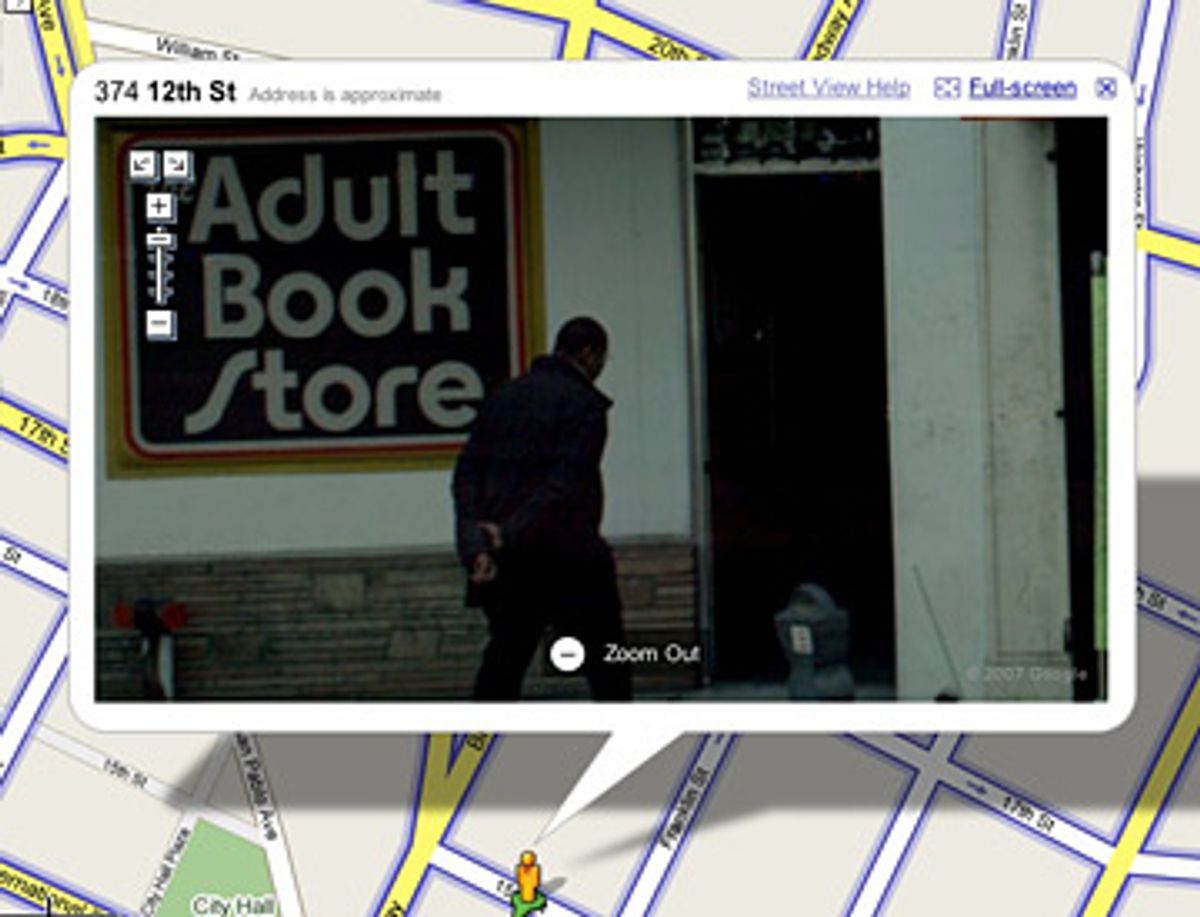

There's one right down the street from you, after all, 367 12th Street in downtown Oakland, a humble little place that goes by the unprepossessing name Adult Book Store. You didn't want to make a show of it, obviously; you kind of ambled inside, hands behind your back, looking but not looking, your gait suggesting confidence and sophistication. And you would have gotten away with it, too, if it weren't for those nosy geeks down in Mountain View: Of all the sin joints in all the towns in all world, you had to walk into the one that, at that very second, was being trailed by a VW Beetle pimped out with an 11-lens digital camera that was taking in everything it saw, and posting it all to Google's servers. Now there you are on Google Maps, memorialized in your moment of weakness, and the whole Web -- even Matt Drudge! -- is laughing at your accursed luck.

Such is life in a time of Google Street View. Earlier this week, Google Maps debuted a system that offers 360-degree snapshots of thousands of addresses in five cities across the country (San Francisco, New York, Denver, Las Vegas and Miami). The service might come in handy next time you wonder if a certain new restaurant in an out-of-the-way part of town is a hole in a wall, but so far Street View seems to have raised more alarm than acclaim. Google acquired the pictures by contracting with a firm called Immersive Media, which drove camera-equipped cars all around town, capturing not only streets but also everything that happens on and around streets -- people walking (and jaywalking), people loitering, people shopping, people picking their noses, people jogging, people driving cars, and even people hanging around porn stores and strip clubs. Now the Web's atwitter with recriminations. A woman writing in to Boing Boing reported feeling "the shakes" when she discovered that Google's camera saw right into her apartment. Wired's Threat Level blog is compiling a brimming album of pictures of folks caught in not-for-the-whole-world-to-see situations, including one of a man who looks like he's breaking into an apartment building, and another of women sunbathing at Stanford. No one is more exercised than Drudge, who led with the Google story for much of Thursday, linking to several unfortunate Street Views under a banner headline -- SMILE, YOU'RE ON GOOGLE EARTH! -- that nicely distills the overarching fear the project generates: "Could Google have caught me doing something I wouldn't want plastered on the Web?"

Indeed, Google very well might have, and privacy advocates aren't happy. On Wednesday, Kevin Bankston, an attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told CNET that it's "irresponsible for Google to debut a product like this without also debuting technological measures that would obscure the identities of people photographed by this product." Google, in response, pointed out that its cameras had only caught what was in clear view; its images were "no different from what any person can readily capture or see walking down the street," a spokeswoman told CNET. This sounds like a reasonable position. I live just around the corner from San Francisco's historic Painted Ladies, and every time I walk out of my house my image is likely getting sucked into someone's SD Card and uploaded, without my knowledge, to Flickr. It would be unreasonable for me to get upset when this happens; I shouldn't expect my actions to be private, after all, when I'm in a public place where people have a First Amendment right to document what's going on. If you think about it, is Google acting any differently from trigger-happy Japanese businessmen on a first trip to Manhattan?

When I talked to Bankston about the plan on Thursday, he acknowledged that Google's project highlights the tension between free speech and the right to privacy -- a balance that has never been cut-and-dried, but that is growing increasingly uneasy now that "comprehensive surveillance is no longer something out of science fiction." Bankston doesn't believe Google's effort violates the law. "I think they have a First amendment right to document the public spaces we share," he says. Rather, Bankston thinks the project is unethical. Unlike people who post pictures of street scenes to Flickr, Google's plan operates on an enormous scale, and it's completely automated, meaning that it exercises no human judgment over what should and shouldn't be put online. When Google indexes the Web, it follows every Web site's Robot Exclusion Protocol, a machine-readable file that webmasters draw up to tell search engines what should and shouldn't be included in search. There is no Robot Exclusion Protocol for the real world. Google allows people to report pictures that should be taken down from Street View, but by the time you learn that there's a shot of you going into an A.A. meeting, an abortion clinic or attending a political protest -- well, by then the damage may already have been done.

Bankston admits that it would probably have been quite difficult, if not impossible, for Google to have blurred out the people it captured in its street pictures. But he notes that if anyone has the collective brainpower to do that, it's them. Yet even if Google does someday implement a way to cut people out of its street scenes, Street View is simply another reminder of what we're inevitably going to lose in a time of easy recording and distribution of images and other documents: anonymity. Nothing you do is hidden anymore, and while we can argue about whether or not this is a salutary thing -- Bankston argues persuasively that anonymity serves an essential social function; (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous) -- keeping things secret, now, might just be impossible.

Let's come back again to that shot of you walking into the adult bookstore. Panning around the scene, we see a woman window-shopping nearby, and across the street a bus is unloading its passengers. There are several cars, too, moving down the street. If you're ever contemplating visiting such an establishment again, it might be wise to operate on the assumption that all these people are packing cameras. Already, weirdos like Justin.tv are stalking our streets, broadcasting all they encounter; is it really fantastical to think that in five or 10 years' time, everyone might be recording everything? Likely not. Watch out.

Shares