Now my friends are gone/ And my hair is gray/ I ache in the places where I used to play/ And I’m crazy for loving/ But I’m not coming on. — Leonard Cohen, “Tower of Song”

Lately I’ve been asking myself: When did I get so damn old?

Will it be on Saturday, when my son graduates from high school? Did it start 10 years ago, when my knees gave out and I had to say goodbye to sports other than bocce ball? Was it last week, when I saw my reflection before I was ready and was shocked by the man with thinning hair and white in his beard who looked back at me? Was it five years ago, when a doorman in Copenhagen stopped me as I was about to walk into a club filled with 20-somethings with the soul-shriveling words, “There’s nothing for you here, sir”? Or did it start decades ago, a long defeat measured in fears not overcome, things not said?

It’s all of these things, and none of them. Aging is an imperceptible and abstract process — until it rears up and bites you in your increasingly southward-aiming ass. And then it’s still imperceptible and abstract. If life is a long dying, how can you single out one moment when you cross the line into the homestretch? What bifocals can you get that will let you see the enormous changes that are happening to you in slow motion?

The worst thing about being middle-aged is when you realize that you haven’t gotten old enough, that your wisdom hasn’t kept up with your years. Around seven or eight years ago, my uncle Mark, who was about 75 then, told me something I’ve never forgotten. Mark is a retired farmer. I always think of him climbing on his tractor in his khakis, a ramrod-straight Nisei who got up at 6 in the morning most days of his life to work his almond farm in the Central Valley. Without any self-congratulation, with a kind of bemused wonder, he told me, “You know, it’s the strangest thing — I still feel like I’m 35 years old.”

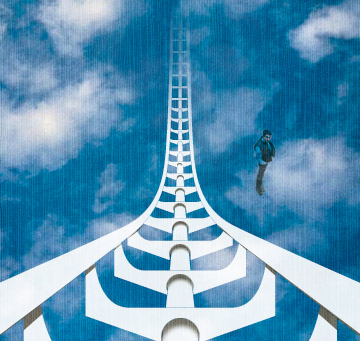

According to our cultural myths, this should have been an inspiring statement. None of us want to get old. We all shuffle drearily forward under the banner of Peter Pan. So the idea that we don’t think we’re old even when we are should be encouraging. I suppose it can be. But there’s also something disconcerting about it. It’s all well and good to be forever young, but I want to feel my age. I don’t mean the aches and pains, but the experience, the serenity, the wisdom that are supposed to come with the years. The long view that you should have when you’re at the summit.

But lately, all that talk of serenity and wisdom is starting to feel like a myth put out by some P.R. firm to keep those of us who have hit the half-century mark from seeking out Dr. Kevorkian. I have noticed zero increase in sagaciousness, but considerable loss of speed, short-term memory and hair. Dylan Thomas urged us to rage against the dying of the light — why shouldn’t we rage against the expansion of our waistlines and the sagging of our boobs?

Of course, a lot of us do. America has a multi-zillion-dollar time-machine industry, catering to the noble rebellion — also known as vanity and desperation — of those who don’t like what they see in the mirror. I haven’t yet succumbed. Somehow the idea of hauling myself down to the Porsche dealership or the Hair Club for Men conjures up nightmarish images of the barber in “Death in Venice,” that rouge-smearing demon who coos to the doomed Aschenbach, “I will restore what belongs to you immediately.” But that’s a minor detail. I’m in the same predicament. I’ve reached the highest point on the roller coaster, I can see the start and the finish of this ride and am trying to figure out what to do with myself on the rest of the way down.

When the bad news about life hit Dante, he compared it to finding himself in the middle of a dark wood. Dante’s spiritual despair has degenerated into our “midlife crisis” — an expression that conjures up tiresome images of chest-beating middle-aged men doing extreme sports, acquiring trophy wives and generally comporting themselves like those burghers fondling the cleavage of peasant girls in late-medieval paintings of “The Triumph of Death,” oblivious of the fact that leering skeletons have seized their ankles and are about to pull them down to hell.

Of course, Dante’s crisis probably wasn’t precipitated by a receding hairline. And if it was, he wasn’t a Porsche kind of guy (and Beatrice was about as far from a trophy wife as you can get). But questions that come up “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” — midway upon the journey of our life — are basically the same. The things you carried don’t seem to work anymore.

Some people turn to the same thing to which Dante did: God. By positing a higher power, they dignify the world, make it deeper, more consonant with the shadows that creep longer as we move toward the end. Critics of religion from Ludwig Feuerbach to Christopher Hitchens have dismissed faith as a childish consolation, a fairy tale humans tell themselves to ward off primordial fears. Of course they’re right. But a nondogmatic, open-ended faith — perhaps an oxymoron, but believers have always been far more interesting than their beliefs — also does, or can do, something subtler: It restores the tragic sense of life.

Still, for many of us, for various reasons, God isn’t an option. And even if he, she or it exists, it seems a bit excessive to bring in the Almighty to console us for angst triggered by liver spots.

But if Porsches, hair weaves and God are off the table, what’s left? Nothing. Nothing’s left. There’s no hope. And once you realize that, you can start to live again.

Our first and most arresting intimations of old age involve physical transformations, the sudden realization that you are no longer the same person. Movies like “The Fly” play off this primordial dread. When I was about 18, I bit down on something and a tiny piece of the top of one of my teeth broke off. I still remember the sinking sensation: I can’t even count on you? And this opens onto a deeper dread — the knowledge that not just our bodies, but our very identities, are not fixed. That we ourselves, our very beings, are mutable. If you’ve ever looked through a colonoscope and seen a tumor growing inside your intestines, you know the feeling. The mind-body problem is instantly solved: They’re the same. And they’re both going down.

But you get over it. This is the hand we’ve been dealt. In moments of vision, what we realize is that the truly destructive change, the only one that can really make us old, is when we stop changing.

For most of us, alas, stasis seems to be the default. The terrible line that opens T.S. Eliot’s “Ash Wednesday,” “Because I do not hope to turn again,” is our motto. And making it worse is the obscure fact that it’s self-defeating. Trying to find the river, we dry up. Trying to hold onto that part of us that once moved, we freeze. We grasp desperately at our past, searching like happiness junkies for lost days when we remember being alive.

But resisting old age makes you old. It makes your losses serious. When you accept those losses, on the other hand, they become comic. You defeat old age by making friends with it. By letting it win. And you might as well, because it’s going to anyway.

By comedy, I don’t mean simply cracking jokes about our impending decrepitude and doom — although that’s an excellent idea. Nor do I mean an approach to life that refuses to acknowledge tragedy. I mean a spirit of regeneration, one that paradoxically springs from an abandonment of illusions. The comedic attitude offers a kind of resignation, a calm surrender to the inevitable. And it’s regenerative because it doesn’t see change as the enemy. It’s an invincible, self-fulfilling belief, one that bubbles up from somewhere unseen.

The comic state of mind is irrepressibly buoyant. Take away my knees, it says, and I’ve still got my feet. Take away my feet and I’ll laugh at you all from my wheelchair. Take away my wheelchair and I’m still on the sunny side of the grave.

This may seem like a superficial way to live, all “positive thinking” and blind optimism. But it isn’t. Comic laughter emerges from the darkness. It isn’t naive. It coexists with tragedy, but it cannot be defeated by it. It gets, literally, the last laugh. The man of comedy has experienced the pain of life, been staggered by its strangeness. He turns his staggering into a self-mocking dance. His laughter does not deny his losses. It is built on them.

And it is open to the air. For the real virtue of the comedic spirit is not that it preserves you as you are, but that it lets you change.

“I was so much older then/ I’m younger than that now,” the poet sings. It’s a command. But to keep getting younger, you have to let go of the carapace of your identity and surrender to the unknown. To become who you are, as Nietzsche eloquently put it, you must have faith in the unknown. Because it is the unknown, the world, that sculpts us into the most beautiful shapes. Our own artistry in forming ourselves is nothing compared to the wind, the waves on the beach, the flames. These are the forces that shape children — it’s why their faces carry so much light.

And the faces of some older people have it, too, that inner glow. It doesn’t come from collecting and piling up experiences and knowledge higher and higher until you are the top dog. It comes from something more humble. In Marcel Camus’ 1958 film “Black Orpheus,” when Orpheus is mourning the death of his beloved Eurydice, Orpheus’ friend Hermes advises him to “Say a poor man’s word, Orpheus: ‘thank you.'” It comes from gratitude.

But gratitude doesn’t mean forgetting, or not sometimes mourning the loss of what you had, or were.

In my youth, I played a lot of football. I played until 10 years or so ago. I could outrun 98 of 100 guys and fake out the other two. Then my knees, once the strongest part of my body, broke down. Now I can barely run at all, and even walking is often painful. Like everything that you lose, football now means more to me than it did at the time. Now it stands for a loss, and that blank spot keeps trying to turn into a symbol instead of just a place on my map. The same holds true for other things I’ve lost — and some of the losses were a lot more important and painful than football. They’re gone, and they’re not coming back. And sometimes it hurts to remember.

But that’s all too self-pitying, and self-mythologizing. I had my day, and I’ll have other ones. We all have our losses — and a lot of people’s are infinitely bigger than mine. Yes, it’s hard to look down from the top of the hill at the rest of your life — no more illusions, this is it — and realize how many things you aren’t ever going to do. But there would be no possibility without impossibility. Besides, the view from up here is beautiful. It’s like you can see forever.