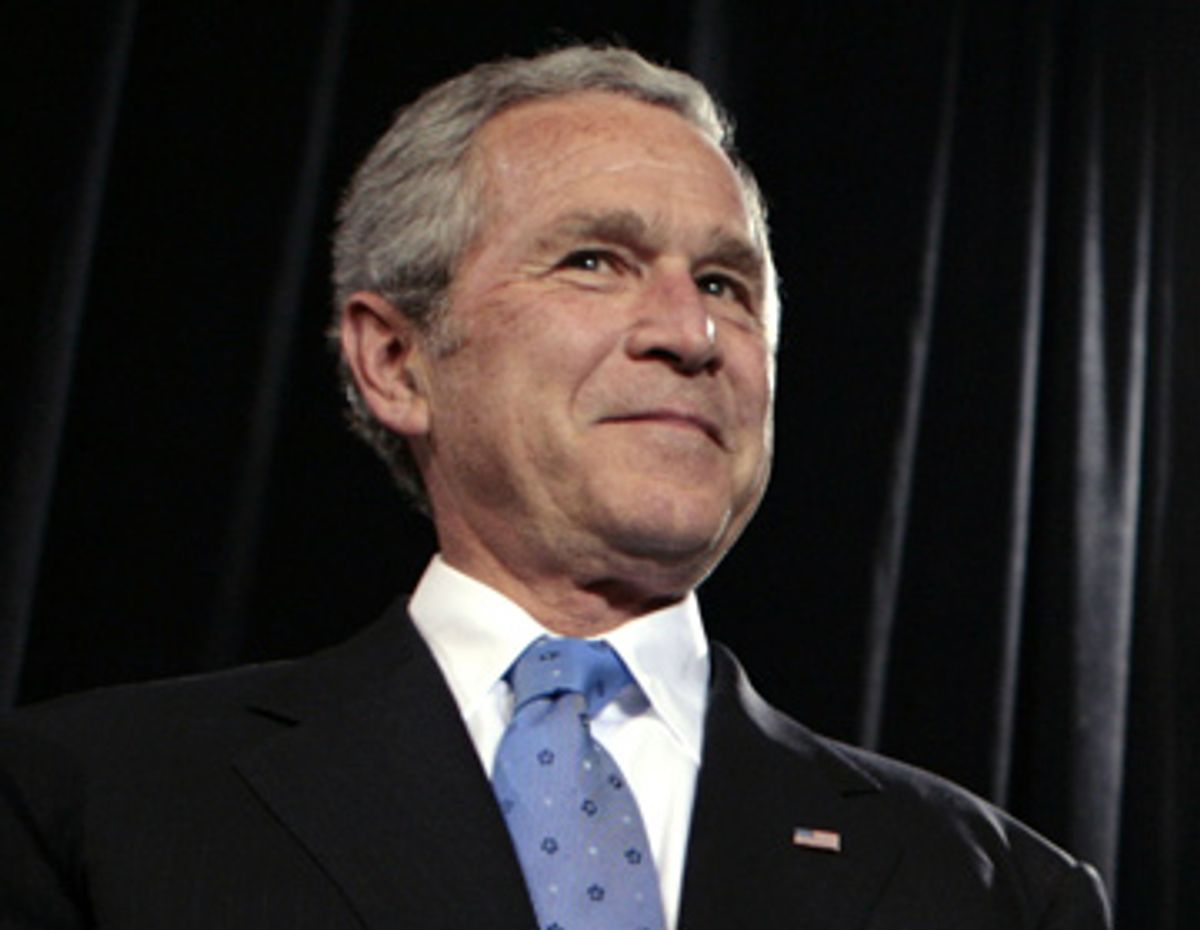

"There's no doubt in my mind that each person who has been executed in our state was guilty of the crime committed." -- George W. Bush, June 2, 2000

"There is no doubt in my mind that Saddam Hussein was a grave and gathering threat to America and the world." -- GWB, Jan. 28, 2004

"There is no doubt in my mind that this country cannot [sic] achieve any objective we put our mind to." -- GWB, April 20, 2004

"There's no doubt in my mind we made the right decision in Iraq." -- GWB, Sept. 2, 2004

"There's no doubt in my mind that Afghanistan will remain a democracy and serve as an incredible example." -- GWB, Jan. 5, 2006

"There's no doubt in my mind [warrantless surveillance] is legal." -- GWB, Jan. 26, 2006

Remember good old doubt? When a capacity for self-doubt was a prerequisite for self-knowledge and a hallmark of maturity? To put it another way, can you imagine John F. Kennedy walking with the swagger of George W. Bush? Kennedy walked like what he was -- a man in pain from injuries he suffered in an actual war, and he allowed himself to be photographed hunched over with worry during the Cuban missile crisis. That picture, now an iconic image of heroic doubt, is sadly anachronistic.

Forty-five years ago today, JFK, speaking to the graduating class at Yale, said, "The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie -- deliberate, contrived, and dishonest -- but the myth -- persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic ... Belief in myths allows the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought." He urged the students to "move on from the reassuring repetition of stale phrases to a new, difficult, but essential confrontation with reality." Kennedy was urging the students not to let the establishment, which he represented, get away with anything. Submit its rhetoric to the fiercest scrutiny. Think for yourself. It was an invitation that reflected his own education, two years earlier, in the wisdom of doubt.

By June 11, 1962, the president had learned the lessons of the Bay of Pigs disaster well. His Yale speech seemed infused with regret at not having treated the CIA's intelligence with more skepticism before the invasion. (The agency had promised that the exiles could "melt into the mountains" if the plan failed -- mountains that it failed to notice were 80 miles away.) The speech also foreshadowed his own fierce scrutiny of the rhetoric of Gen. Curtis LeMay and other administration hawks, who urged an attack during the missile crisis.

Six years after the speech, George W. Bush graduated from Yale and went on to confront reality with a vengeance, or, more accurately, ignore it all together, as Ron Suskind noted in "The One Percent Solution," when he famously quoted a White House aide dismissing journalists and historians as "the reality-based community." But it would be lazy and wrong to think of George Bush as the source from which the modern disdain for doubt flows. The truth is, we, as a culture, don't value self-doubt the way we did in the time of Kennedy or of other famous doubters, like Lincoln or Jefferson. We have created the political culture of mythology JFK warned us about. We have the president and, as the recent presidential debates have shown, the potential presidents we deserve.

Let's face it, George Bush doesn't have to doubt himself, any more than Donald Trump or Tom Cruise or Mitt Romney do. We live in a culture where they will never be forced to examine their prejudices or flaws. Of course, they have been denied the true confidence of people who are brave enough to face their doubts and who know there are worse things than feeling insecure. Like, say, feeling too secure. Pumped up by steroidic pseudo-confidence and anesthetized by doubt-free sentimentality, they are incapable of feeling anything authentic and experiencing the world. But that hasn't stopped them, and won't stop others, from succeeding in a society that is more enamored of a non-reality-based conception of leadership than previous generations were.

JFK's generation had been warned by FDR about the corrosive peril of fear, and they took the admonishment to heart. But imagine if they had approached their moment in history with the grandiose self-image with which we've approached ours. Without the wisdom of doubt, without the grace of humility and the simple ability to learn from mistakes, would anyone have called them the Greatest Generation? (And by the way, don't we do them a disservice with that moniker -- didn't they fight against all things "greatest" and on the side of splendid imperfection?) Imagine what the world would look like if they'd had the disdain for humility we do, if they'd relied on a conception of themselves as innately good, if they'd allowed themselves to think they knew everything and therefore learned nothing.

But our generation has erected a culture that confuses happiness with a lack of discomfort, and leadership with an almost psychotic form of false optimism. We have ingeniously insulated ourselves from self-scrutiny and fear. We tuck ourselves away in gated communities, hibernate in food courts, or sleep in front of televisions, swathed in layer upon layer of soft and soporific comfort to protect ourselves from the bracing draft of doubt. We can barely feel our own culture anymore.

Our pretend fearlessness has made us timid. Some of our filmmakers, the Michael Bays and Brett Ratners, make movies as if they're embarrassed by stories, and some of our singers, especially those of the emo variety, sing as if they're embarrassed by melody. Most of us are getting our information from only a few sources, and it's infused with narcotic banality: pillow-embroidery sentiment and locker room aphorisms that induce the waking sleep of consumerism. We've been convinced that good things go to people who "want it more than the other guy," that wealth is a reward, and poverty a penalty. That the highest compliment we can pay each other is, we know what we want and how to get it, which makes us sound brave. But by banishing doubt we have cultivated fear. We've stopped looking under the bed for monsters. The good books and songs and movies, like last year's harrowing "Little Children," have to fight through layer upon layer of swaddling to get to us.

We've forgotten how valuable, even vital, it is to be bravely unsure of ourselves. We've forgotten that doubt is the hill that hope climbs, that without it our spirits atrophy.

You'd think that after the past six years we'd want some of JFK's brand of genuine bravery and capacity for doubt in our leaders, but most of the current candidates for president, with a few exceptions, like Barack Obama, John McCain and John Edwards, again sound like scared little children playing soldier. They puff up their chests and bray in the absolutist style of the guy who got us into the biggest mess of our lifetime. They clumsily and desperately make up facts, conflate enemies, and endorse the worst kinds of behavior, all to seem more certain than the next guy that evil is all around us. They present themselves as even less troubled by reality than our freedom-frying, deaf, dumb and blind dauphin. And at the same time they seem excruciatingly un-free, as if they're straining against the straitjackets of political convention.

Our current presidential candidates could do us all a favor and read the words of a president who had to wear a confining back brace every day and who would often wince in pain, slump with doubt, and exhibit all sorts of human flaws -- but also gave the impression that he could swim three miles in the South Pacific if he had to, even in his suit and tie. Someone who stood up to the fear-mongers of his day with courageous doubt, who knew firsthand that the closest thing there is to absolute evil is absolutism itself.

Shares