I returned from Europe a week before President Bush departed for the G8 summit in Germany. In Rome and Paris I met with Cabinet ministers who uniformly said the chief issue in transatlantic relations is somehow making it through the last 18 months of the Bush administration without further major disaster. None of the nonpartisan think tanks in Washington can organize seminars on this overriding reality, but within the European councils of state the trepidation about the last days of Bush is the No. 1 issue in foreign affairs.

One of the ministers with whom I met, who had supported the invasion of Iraq and had been an admirer of outgoing British Prime Minister Tony Blair's, ruefully cited Blair's remark about Iraq at his joint press conference with Bush on May 17 at the White House: "This is a fight we cannot afford to lose." "Cannot? Cannot lose?" mocked the minister. "Should not have lost."

High officials of European governments describe U.S. influence as squandered and swiftly eroding (one minister went down a list of Bush administration officials, rating them according to their stupidity), the country's moral authority nil. Lethal power vacuums are emerging from Lebanon to Pakistan, and Europeans are incapable on their own of quelling the fires that burn far closer to them than to the United States through their growing Muslim populations and proximity to the Middle East. They have no illusions that they will be treated seriously as real allies or that there will be a sudden about-face by the Bush administration. Their faint hope -- and it is only a hope -- is that they have already seen the worst and that it is not yet to come. Even worse than Bush, from their perspective, would be another Republican president who continued Bush policies and also appointed neoconservatives. That would toll, if not the end of days, then the decline and fall of the Western alliance except in name only, and an even more rapid acceleration of chaos in the world order.

Bush's procession through Europe was a pageant of contempt, disdain, delusion, provocation and vanity masquerading as a welcome respite from his troubles at home. In Albania he landed at last in a place where he was hailed as a conquering hero. His demolition derby of U.S. influence was presented as a series of bold moves, but it confirmed the fears of the other world leaders at the G8 summit (and elsewhere) that the rest of Bush's presidency will be an erratic series of crashes. His performance ranged from King Nod, issuing proclamations oblivious to and even proud of their negative effect, to King Zog (the last king of Albania). No president has had a more disastrous European trip since President Reagan placed a wreath on the graves of SS soldiers in the Bitburg cemetery. Yet Reagan's mistake was unintentional and symbolic, a temporary and superficial setback, doing no real damage to U.S. foreign relations, while Bush's blunders not only reinforced counterproductive policies but also created a new one with Russia that has the potential of profoundly undermining U.S. national security interests for years to come.

Bush's foreign policy has descended into a fugue state. Dissociated and unaware, the president and his administration are still capable of expressing themselves as if it all makes complete sense, only contributing to their bewilderment. A fugue state should not be confused with cognitive dissonance, the tension produced when irreconcilable ideas are held at the same time and their incompatibility is overcome by denial. In a fugue state, a trauma creates a kind of amnesia in which the sufferer is incapable of connecting to his past. The impairment of judgment comes in great part from a denial of distress. Bush's fugue state involves the reiteration of a failed formula as though nothing has happened. So he proudly reasserts the essence of his Bush doctrine: Our acts are independent of other countries' interests. And he adds new corollaries: Other nations must forgive our unacknowledged mistakes even if we threaten their national security. To this, Bush overlays cognitive dissonance: Our policy is working; it just needs more time. Thus the incoherent becomes coherent.

Bush's amusing gaffes should not divert attention from the gravity of his underlying decline. Though his verbal hilariousness has been present since the beginning, his miscues, misstatements and mistakes now highlight a foreign policy in utter disarray.

Upon meeting Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican last weekend, Bush presented him with a gift of a wooden cane carved with English words. When the pope asked the president what they were, Bush told His Holiness, "The Ten Commandments, sir." To sir? With love?

In Rome, on June 9, a reporter asked Bush about setting a deadline for Kosovo independence. "What? Say that again?" "Deadline for the Kosovo independence?" "A decline?" "Deadline, deadline." "Deadline. Beg your pardon. My English isn't very good." Bush then declared, "In terms of the deadline, there needs to be one. This needs to come -- this needs to happen." The next day, asked when he would set a deadline, he replied, "I don't think I called for a deadline." Reminded of his previous statement, Bush said: "I did? What exactly did I say? I said, 'Deadline'? OK, yes, then I meant what I said."

Before offering that tongue twister, Bush quite deliberately upset German Chancellor Angela Merkel's proposal for climate change at the G8. She put before the summit a program for carbon limits and an emissions trading system supported by, among others, Tony Blair, as his final gesture to burnish his reputation before he leaves office on June 27. Bush countered with a proposal for voluntary limits that would have to be approved by China, India and other major industrial countries that would not agree. In short, Bush's program was no program at all, except as a gambit to push aside Merkel's. With that, Bush demolished the possibility of any positive plan emerging from the summit. He also deprived Blair of a last achievement. Were it not for his relationship with Bush and support for his Iraq policy, Blair would not be leaving Downing Street. He has sacrificed his career to Bush's fiasco. His advice on the reconstruction of Iraq ignored, his advocacy grew more passionate. From whom much has been asked, nothing has been given.

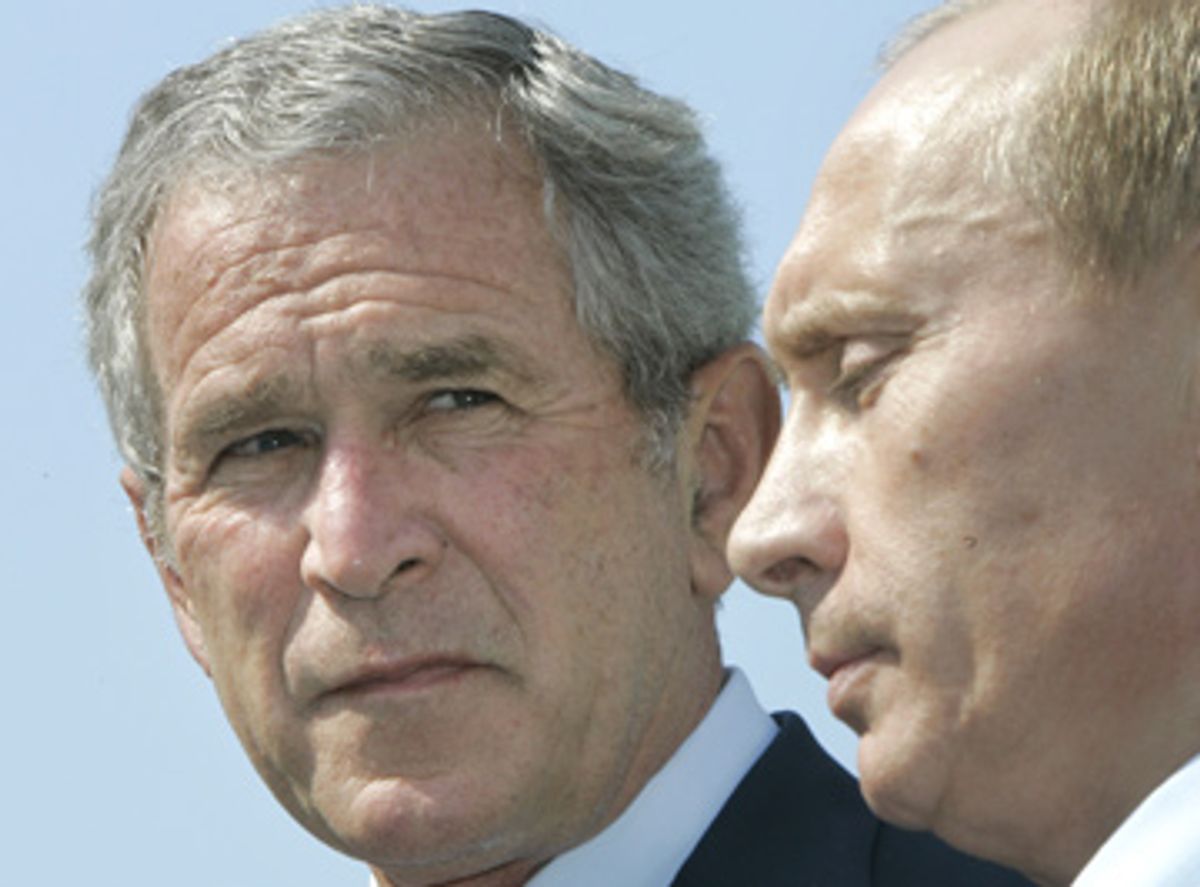

While Bush was undermining traditional allies, Russian President Vladimir Putin was making child's play of him. Bush's proposal to put tracking stations for a missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic gave Putin his opening. In response, he offered a radar site in Azerbaijan to be jointly operated by the United States and Russia. Bush had deployed the wrong tactic on behalf of the wrong strategy. Bush's missile shield has not been proved to work, has cost hundreds of billions of dollars, and has an uncertain purpose. Is the plan meant to reassure eastern European nations of the former Warsaw Pact, Donald Rumsfeld's "new Europe," against Russia, or is it a short-term ploy to rally support in the one region in the world that still likes Bush because of deep residual pro-Americanism? If Bush intended to persuade Putin to temper his authoritarianism, he only succeeded in antagonizing the Russian leader. As Bush's "freedom" agenda has collapsed, he has reverted to a Plan B for a new ersatz Cold War. His ham-handed move allowed the adroit Putin to change the subject and corner him. Meanwhile, the engagement of Russia in areas of mutual interest -- containing Iran -- languishes.

In Iraq, Bush's policy is now to arm all sides in the sectarian civil war between Shiites and Sunnis. He claims to be devoted to nation building, which he previously dismissed, while he presides over a mass exodus of 2 million Iraqis, upholds law and order while holding tens of thousands of prisoners without due process, and conducts a "surge" of troops to secure the capital city of Baghdad whose main effect has been to facilitate its ethnic cleansing. The Iraqi government, for its part, has not met any of the benchmarks in reforming its laws demanded by the United States as the sine qua non of continuing support.

And where in the world is Condoleezza Rice? While Bush was in Europe, the secretary of state was at home. Instead of attending the summit, she delivered a speech at the Economic Club of New York, announcing that the new doctrine of the administration henceforth should be called "American realism." Until that moment, we were supposed to refer to it as "transformational diplomacy." Rice, the former realist turned neoconservative fellow traveler, seemed to have come full circle. But what was it exactly that she was doing with her rhetorical adjustment?

Rice's frenetic but feckless diplomacy in the Middle East has been fruitless. She is unwilling or unable to break beyond the bounds that Bush establishes, forbidding relations with Syria, for example, and thus guaranteeing her failure.

As she shuttles endlessly and meaninglessly, neoconservatives within the White House undermine her foredoomed initiatives. Elliott Abrams, the deputy national security advisor for policy, in briefing a meeting of Jewish Republicans, said that Rice's "talks are sometimes not more than 'process for the sake of process,'" the Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported on May 14. According to Haaretz, "Those attending the meeting of Jewish Republicans understood Abrams' comments as an assurance that the peace initiative promoted by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice doesn't have the full backing of President George W. Bush." As she engages in an academic exercise to rebrand empty rhetoric with new empty rhetoric, the neocons continue to create a parallel foreign policy.

Rice contradicts herself but forgets that she has. Bush continues to prattle about "freedom" but cannot remember his benchmarks. Only Dick Cheney remains consistent. The new mission statement is the old mission statement. The new scenarios are the old delusions. Time marches on.

Shares