Could it really be? Is the NAACP, the civil rights group that rocked the entire planet so hard that even the students in Tiananmen Square invoked it, really on the verge of collapsing with a willfully self- destructive whimper?

With Bruce Gordon's recent departure as president after just 19 months and the recent announcement that the NAACP is shuttering its regional offices, the future does not look bright for the nation's oldest advocacy organization.

Back in the late '90s, I was fresh out of law school and raring to take on the system with the tools that NAACP and other civil rights leaders had won for me. Working in D.C. at the time, I remember seeing a photo of then NAACP president Kweisi Mfume in the paper. I was transfixed by the reverential image of him being arrested outside the Supreme Court during a protest against the dearth of black law clerks -- an essential steppingstone for young lawyers wanting to enter the upper reaches of the legal profession. Eyes closed, on his knees, handcuffed, he looked with beatific stoicism to the heavens, à la Dr. King en route to the Birmingham jail. A shot for the ages.

But as inspired as I was by traditional civil rights activism, I was also having some nagging doubts about the efficacy of the old-school struggle the world has been watching us play out since the '60s. After two generations of activism (preceded by NAACP's earlier dogged war against Jim Crow, beginning with the group's founding in 1909) racism has changed. Thanks to the sacrifices of the heroes and the martyrs, the battle against overt white supremacy has been won, however imperfectly. Now a critical bloc of black professionals are entering the halls of power and the black masses have a real, though obstacle-strewn, shot at achieving the dream.

As I studied Mfume's photo, I couldn't help thinking: Shouldn't the NAACP have been using its moral authority to extend black influence throughout the nation's institutions instead of submitting those institutions to unceasing frontal attacks designed merely to expose their racism? Instead of playing the faux martyr on the steps of the Supreme Court, shouldn't he have been inside, respectfully but firmly lobbying Clarence Thomas and any other justice he could buttonhole? Holding my newly minted law school diploma, I was beginning to think so. It was time for the NAACP to evolve into a problem-solving organization for black America.

That's why I was thrilled when the NAACP tapped veteran businessman Gordon to lead the black community into the future. Finally, after the organization had spent years clinging to a focus on confrontation without much action, Gordon promised to retool the NAACP to focus on social services and to leverage the civil rights movement's gains into practical results. A star businessman whose career had been made possible by organizations like the NAACP, he was living proof that black success now requires more pragmatism than protest.

With a membership that peaked during WWII, long-running budget shortfalls, and a leadership and membership dominated by politicians, preachers and the elderly, the NAACP was in danger of becoming all but irrelevant. A history of poor management and disagreement with the group's protest-focused agenda dried up the corporate and philanthropic monies that had earlier bankrolled black freedom. When former Verizon exec Gordon was named president in 2005, it seemed a tacit admission that America had changed, and that the NAACP would change, too.

Gordon was the ultimate insider motivated by a social accountability ethic born from the civil rights struggles that made his success possible. He had long used his clout, working from within, to significantly increase minority hiring and training programs in the telecom industry. "Civil rights leaders throughout this country did what they did and died," he said in his acceptance speech, "so my generation has full responsibility to walk in the doors those brave people opened."

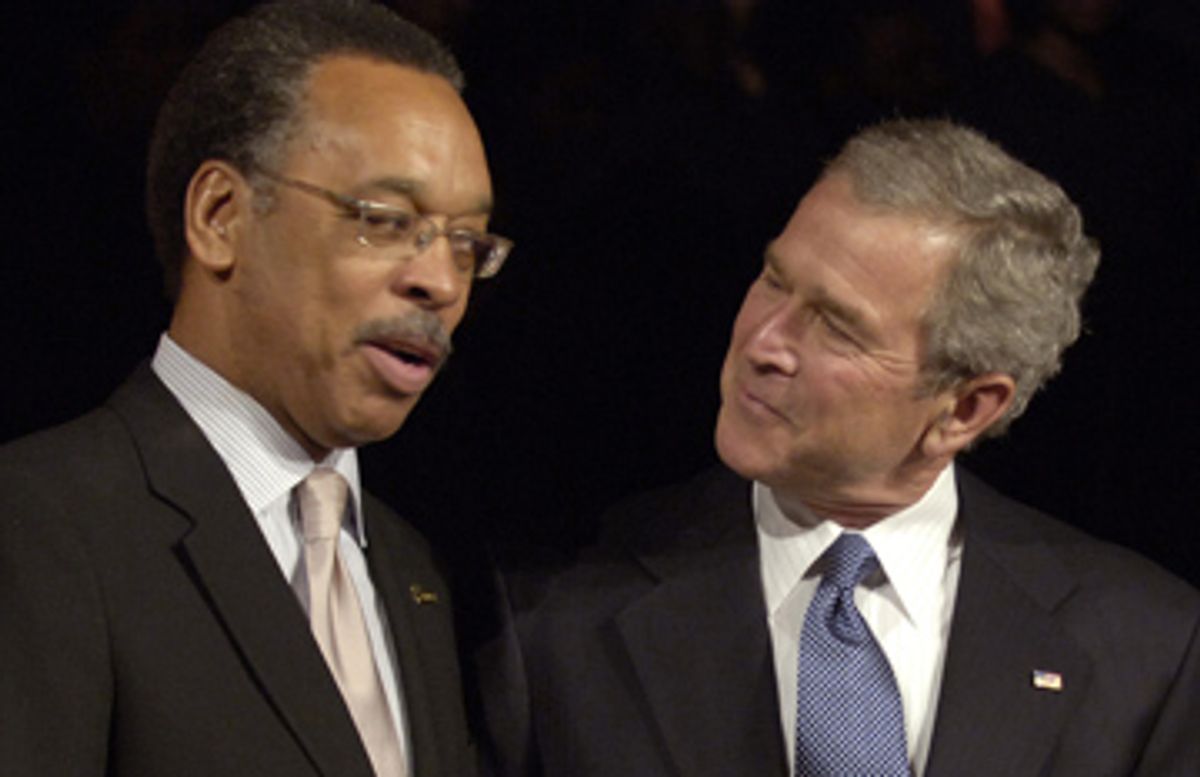

In his brief tenure, Gordon used his corporate ties for Hurricane Katrina relief and brought in staffers with résumés impressive enough to lift morale in the beleaguered organization. He met three times with President Bush, who had shunned the NAACP for nearly six years. But after 19 months of constant warfare with the NAACP's board over his lack of interest in protest, he was out. With him went the corporate funds and credibility desperately needed to save the NAACP.

In defending the NAACP's change of heart about the leader who was doing exactly what he'd been hired to do, Julian Bond, chairman of NAACP's ungainly 64-member board of directors, said, "Put simply, we fight racial discrimination and social service groups fight the effects of racial discrimination. Service is wonderful and praiseworthy and fabulous, but many, many organizations do it. Only a couple do justice work, and we're one of those few."

Gordon's departure was only the beginning of NAACP's troubles. Now, just three months later, the group has announced it will be "temporarily" closing its seven regional offices and slashing its national staff by 40 percent. It has also had to "delay" moving its Baltimore headquarters to Washington, D.C. The nation's oldest civil rights organization is on the brink of extinction, defeated by its inability to evolve, a fact that no amount of rhetoric will be able to conceal at its 98th annual convention next month.

If it had been up to me to join a Freedom Ride or face Bull Connor or be spat upon and dragged from lunch counters to a Deep South jail, I'd be cleaning Salon's office today instead of writing this column. I am in awe that civil rights activists, symbolized by the NAACP, found the courage, and indeed the hope, to lay their lives on the line in a seemingly lost cause. Which is why it breaks my heart to be writing this. Those of us who were not required to find out what we were made of then are required now to find the courage to speak truth to a venerated black power that has lost its way. Sadly, the NAACP seems to have outlived its usefulness.

Shares