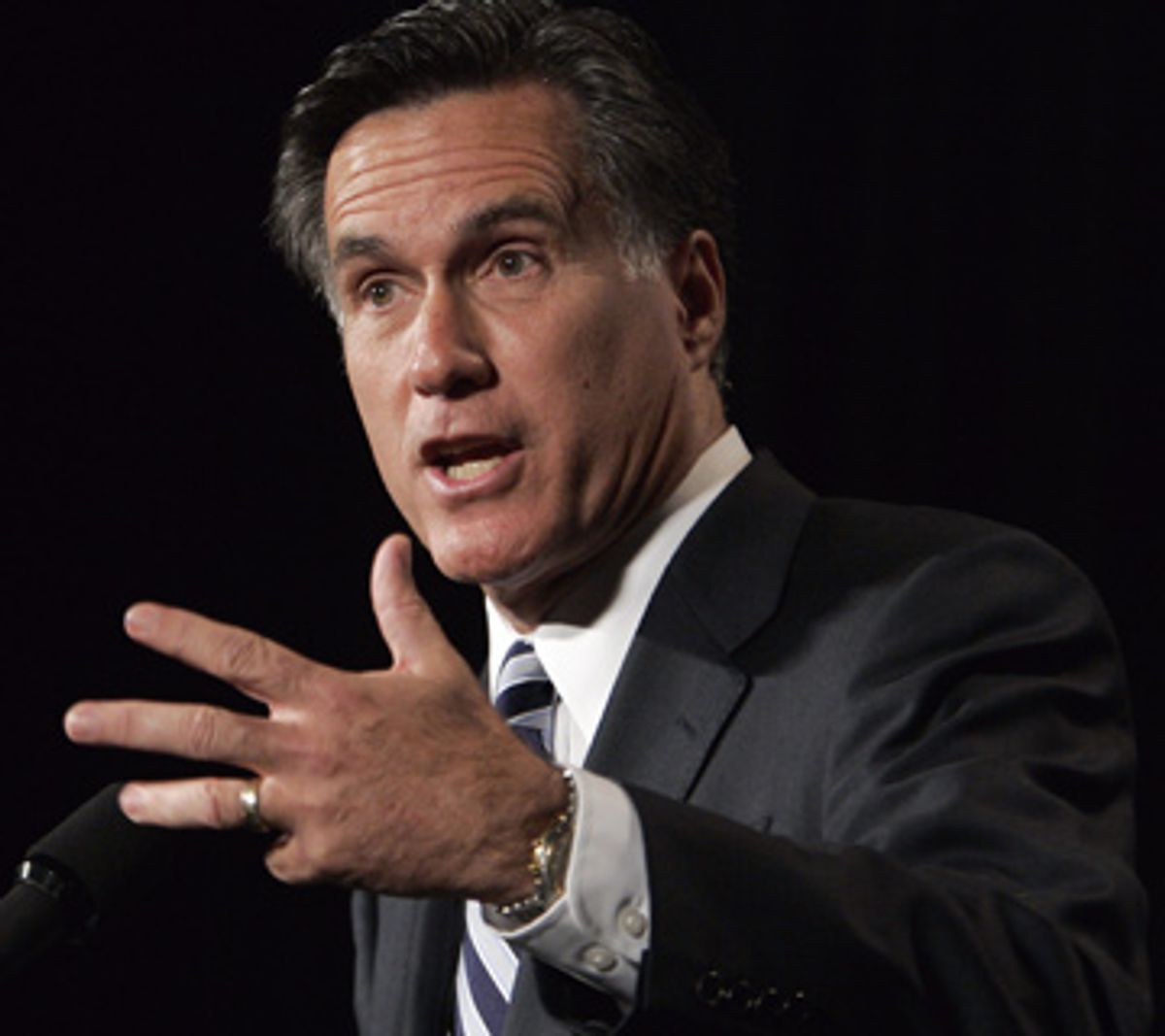

Corporate wizard Willard Mitt Romney has entered the next phase of his presidential initial public offering: Appearing in shirt-sleeves.

As he comes out before a town hall crowd of about 200 in early June, his suit jacket is missing, his pleated pants ride high and his starched white cuffs are turned twice on each wrist -- not rolled to the elbow like those of a working man or George W. Bush, but just a few inches up the arms, far enough to show that he is not wearing a Rolex. He has been campaigning all weekend in Iowa, eight public events in three days, and his local spokesman says that the jacket started coming off on Saturday, which coincidentally was the same day that the New York Times ran a front-page story with the headline "Romney Struggles to Connect on Stump."

Romney's appearance sans jacket tells the story of that struggle. For 25 years, he conquered corporate America, a place where the suits hang perfectly, the silk ties have tight knots and the presentations come in PowerPoint. Now he is campaigning to lead the Western world, and the rules are different. It is not enough to simply have a set of strategies or the most powerful financiers. He has to become someone people can believe in. He has to step outside his suit and appear to be more than just another rich guy. Though he currently leads the GOP in fundraising and the New Hampshire and Iowa polls, this is still a work in progress.

"In the private sector, things get better," the former Massachusetts governor tells the Muscatine crowd, his suitless shoulders looking narrow, his arm holding the microphone at a perfect right angle. "You make better products year after year, or you are going to go out of business, because your competitor will do a better job. You don't make something better, someone else will."

This is the Romney ethos. He is building a better presidential candidate: New and Improved! Smoother, Smarter and Stronger! Devoted and Effective! Ready to Lead!

Unlike John McCain and Rudy Giuliani, Romney says what a plurality of Republicans want to hear about every issue, whether it be abortion, immigration or the war in Iraq. He appears passionate about the things Republicans are passionate about. He looks like a president should look. He has a family cut from a television sitcom. He does everything he is apparently supposed to do. Ask him a question, and there is a pause before his answer -- he seems to search the files in his brain, double-checking that he is not making a mistake. Then he delivers sentences straight from a memory bank of sound bites.

Immigration? "I love legal immigration. I want to end illegal immigration. This is not rocket science." Energy problems? "We are going to spend whatever it takes to rid America of its dependence on foreign oil." The war on terror? "We'll beat the jihadists by supporting moderate Islam and having a strong military." Gay marriage? "Marriage is primarily an institution for the development and nurturing of children, and therefore I would restrict marriage to a relationship between a man and a woman."

Back in February, the Boston Globe obtained a Romney campaign PowerPoint that explained the "Primal Code for Brand Romney." It said he would campaign as the anti-John Kerry, even though Romney has changed positions at least as many times as the last man to be labeled a "flip-flopper from Massachusetts." It called for Romney to contrast himself with France, even though he spent his formative years as a Mormon missionary in Paris and Bordeaux. It targeted the "European-style socialism" of Hillary Clinton, even though Romney passed a statewide program mandating private health insurance for every citizen.

For months now, Romney's rivals have been trying to use these contradictions to put a dent in his full head of frosted hair. They point out that Romney voted for Paul Tsongas in the Democratic primary in 1992, before he registered as a Republican. He supported abortion rights before he opposed them. He supported gay rights before he campaigned against gay marriage. He favored waiting periods for gun purchases before he joined the National Rifle Association. He liked campaign finance reform until he decided not to like it.

Most of these critiques miss the point: There is a solid core to Romney's character. He is at the deepest level an accomplished capitalist, efficient and effective, who has defined himself through the decades by giving the marketplace what it wants. All campaigns try to turn their candidates into a product. Romney distinguishes himself by attempting to eliminate any difference between that product he has created and the person he really is. Behind all the flashy direct-mail pieces and television spots, there remains a man who fundamentally relates to the world as a series of spreadsheets to be analyzed. "Mitt Romney," the PowerPoint reads, burrowing into the heart of the brand, "tested, intelligent, get-it-done, turnaround CEO governor and strong leader." But it is unclear whether America will embrace a bona fide corporate candidate.

On the stump in Iowa and New Hampshire earlier this month, Romney was most comfortable and persuasive when he entered the mode of chief executive. He can lucidly parse complex economic data, like the share of the gross national product that goes to military spending, U.S. economic growth rates or his plan to cap federal growth at "inflation minus 1 percent." He can be passionate about currency policy, the need for improved education to compete with China, and America's economic future in a globalizing world. "I think the way a smaller nation, like us, stays ahead of a much larger nation, let's say India or China," he said at one stop, "is just by having superior technology and innovation. That's how you stay ahead forever."

If you took every American president since William Taft and put them in a room, they would still probably have less collective business experience than Romney alone. Herbert Hoover worked as an international mining consultant. Jimmy Carter was a peanut farmer. The current President Bush got a Harvard MBA, but his only real success was financially reviving a mediocre baseball team. By comparison, Romney is a business god. As an investor, he helped build up brands like Staples, Duane Reade and Domino's Pizza. He bought and sold companies that made paper, bicycles, bowling alleys and surgical instruments. A few years ago, an analyst at Deutsche Banc calculated the profitability of Bain Capital, the private equity firm Romney ran from 1984 to 1999. It listed the rate of return at 173 percent per year. The U.S. stock market historically grows at an annual average of about 11 percent.

But his strength is also his weakness. What dazzles in the boardroom fizzles on the campaign trail. Consider, for example, Romney's penchant for mathematical metaphors. "Null set," he said at the Republican debate on June 5 in Manchester, in a bizarre and cryptic response to a simple question about Iraq. The next day he spoke to employees of a manufacturing firm in Hudson, N.H. "I think we face as a nation one of these great, if you will, inflection points," he said. A few minutes later, he tried to connect with the working man: "I went to high school just like you guys did."

The next stop was Concord High School, where he was asked a question by a moppy-haired kid, wearing a camouflage baseball cap, a basketball jersey and a set of stereo headphones around his neck. Romney, in geeky dad mode, tried to make a joke with -- of course -- another fiscal metaphor. "You seem to be a known commodity here," he said, breaking a cardinal rule of high school: Never admire someone else's cool in public. The auditorium of teenagers mumbled a confused response. A couple of hours later, he was back in Manchester for another "Ask Mitt Anything" town hall meeting. A man took the microphone to say that his brother is serving in Iraq, and then asked what Romney will do to build support for the war on terrorism.

"Thank you. First of all," said Romney, "I hope that by the time -- if I am lucky enough to be elected president -- by the time I'm there, that the surge has worked." Then he realized his mistake. He drew too quickly from the memory bank of sound bites, and ignored the emotional weight of the man's question. "First of all, as well," he corrected himself, "Thank you [to] you and your family for the sacrifice of your brother. We appreciate every person who serves our nation."

There is little doubt that Romney will soon learn to avoid such mistakes. It is part of his DNA -- improve the product, or go out of business. So the jacket came off in Iowa 10 days later. Next he might loosen the tie. The metrics are constantly monitored. After spending more than $2 million on television spots in early voting states, he is ahead in the polls, and his business connections have rocketed him to the front of the fundraising race by banking $23 million in the first quarter. "We do employ models of business efficiency," explains Kevin Madden, Romney's campaign spokesman. "The governor's leadership style sets an example for how the campaign operates ... Rather than sticking to the old campaign models of 'spending money,' instead we look at how we can invest our resources to yield a greater return."

But success in the primaries is far from certain. Voters think a lot more about choosing a president than choosing a diet cola. In Massachusetts, Romney was derided by the Boston Globe for being "Slick Willard." In the New York Times, he has been called "Governor Perfect." Voters, or maybe just journalists, want flaws. They want a human. As it stands, Romney's greatest failing is that he is afraid to show himself off script. In Iowa, his handlers kept reporters at a distance through multiple stops. The message was clear: Don't disrupt the choreography.

Then, in Muscatine, a local television news lady tried to break the rules. She simply walked up to Romney with her cameraman after the event, while he was shaking voters' hands. His Iowa spokesman swore under his breath and rushed across the room, but by the time he got there, Romney's security had already intervened. The question went unanswered. Romney, still smiling, moved on.

This was on Father's Day, an occasion when the campaign released an oddly intimate 13-minute video of the Romney family Christmas vacation last year. On the Romney campaign Web site, his five grown sons posted a message to their father. "We are so proud of you," they wrote. Then they posted their father's e-mailed reply: "We sure are proud of you! Love Dad." Maybe this is the way the Romney family really interacts, but it's hard to know for sure.

So little in his campaign is being left to chance. If Romney has nothing to hide, if he really is the altruistic executive he claims to be, then at some point he is going to have to drop his guard, put down the PowerPoint and face the voters as himself. Only then will America know if the master of the boardroom deserves a chair in the Oval Office.

Shares