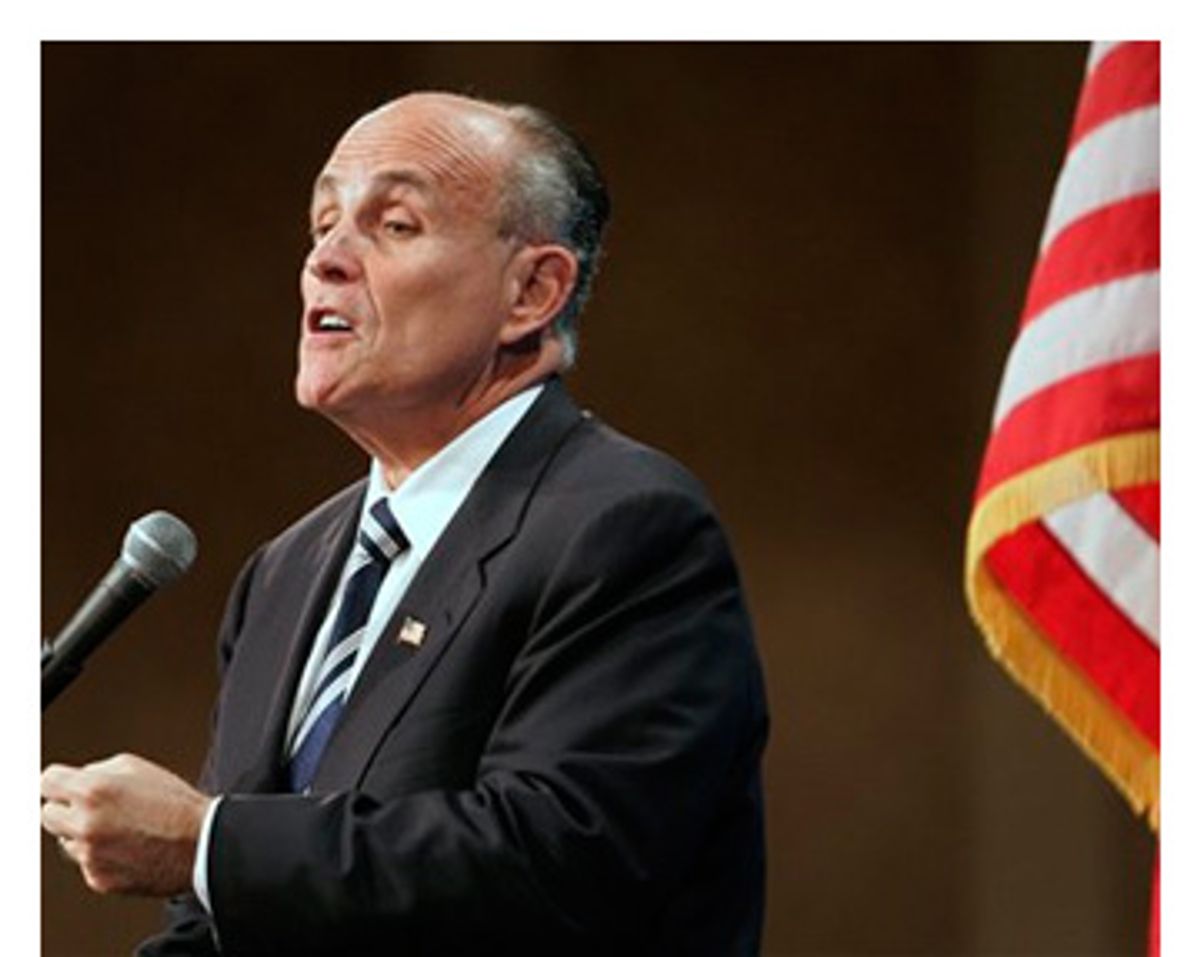

The conventional wisdom is that Rudy Giuliani's bid for the Republican presidential nomination will be in serious trouble without the support of evangelicals and social conservatives. It is still early in a wide-open race. But with his campaign appearance on Tuesday at Regent University, the school founded by conservative televangelist Pat Robertson, the former mayor of New York City showed that he was still struggling with a strategy for social issues important to the party's conservative base.

When the first question from an audience member came in two parts, Giuliani embraced the chance to avoid dealing with social issues altogether. He was asked how to appeal to Muslims who are not religious extremists and how to "get Judeo-Christian values back in our government" -- conservative code for issues like abortion and same-sex marriage. Giuliani went off on a rambling answer about Islam that took him to the streets of Saudi Arabia and into the politics of the Soviet Union, before skipping on to the next question from an audience member.

When pushed for clarification at a press conference later in the day, Giuliani said he had simply forgotten to answer the latter half of the audience member's question. "You can't possibly describe Judeo-Christian values in one lesson or two or three, but if there was one, it would probably be Jesus' admonition that you would be judged based on how you treat others, and I would try to exemplify that in the way that I governed as president," Giuliani explained. "I think that Judeo-Christian values are so much a part of America that if you run a government responsibly and honestly and peacefully, you're reaffirming Judeo-Christian values." He never mentioned abortion or same-sex marriage, intelligent design or prayer in schools.

There are obviously still some kinks to be worked out, some questions for which the Giuliani campaign has not yet developed clear answers. But a strategy for how Giuliani can deal with these issues does appear to be developing: Rather than pander to the base and risk looking like a flip-flopper, he implicitly acknowledges the differences between him and evangelical voters on social issues and moves on -- while continuing to emphasize his image as "America's mayor," the one many Americans remember from 9/11 as a strong, decisive leader. That, the campaign wants voters to think, is the most important quality to look for in a president this time around, because of Islamic extremism and the war in Iraq.

But there are several points on which Giuliani splits with evangelicals, and none is more evident than abortion, an issue on which Giuliani has made a few gestures toward religious conservatives while remaining pro-choice. That balancing act has created difficulty for the campaign, however. Giuliani's speech here was a little like the recent hit comedy "Knocked Up," where the issue of abortion -- and why the hell no one was talking about it -- was an unspoken but perpetual presence until one character, fed up with the refusal of those around him to discuss it, started talking about "shmashmortion." Giuliani never uttered the word "abortion" during his speech.

Asked later at the press conference whether he had made a conscious decision not to mention it, Giuliani dodged by saying that he'd given his standard leadership lecture -- one he'd given a few hundred times with little variation -- and that if he had changed the speech to explicitly discuss the issue "it would have actually been a conscious decision to go out of my way to mention it."

Still, the issue was a strong subtext of the speech. "Don't expect you're going to agree with me on everything," he had told the audience, "because that would be unreasonable. Even I don't agree with myself on everything," he said. "It's not about one issue -- it's about many issues."

Nevertheless, he added that if the election did come down to a single issue for voters, then it should be about the one thing that the former mayor has made a signature issue: the fight against terrorism.

Evangelicals have been a potent force in Republican Party politics. According to most estimates, white evangelicals made up 40 percent of those who voted to reelect President George W. Bush in 2004, and they broke for him over Democratic candidate Sen. John Kerry 78 percent to 21 percent, according to the National Election Pool exit poll. (The only group that came out stronger for Bush, says Democratic pollster Mark Mellman, was Fox News viewers, who went 88 to 7 for Bush.) Furthermore, evangelicals are concentrated particularly heavily in the early primary states. And more than that, over the past few election cycles, evangelicals have been important to the Republican Party for more than just their numbers: They've been its foot soldiers, the driving force behind its get-out-the-vote efforts.

Many political observers have felt that a pro-choice candidate cannot win a Republican primary. But so far, the numbers haven't borne that out. Most national polls currently show Giuliani with a lead over his Republican foes, despite even the recent all-but-entrance into the race of former Tennessee Sen. Fred Thompson. A March survey conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, which did not include Thompson, showed Giuliani leading among all Republicans, including white evangelicals, though his level of support among evangelicals was noticeably lower than it was among other religious groups.

But it's most likely too early to conclude from those results that Giuliani has overcome the evangelical hurdle. National polls, especially ones conducted this early in an election season, tend to be more about candidate name recognition than voters' support for a candidate's positions. It may be that evangelicals thus far know Giuliani only as "America's mayor," not as someone who's pro-choice. In a survey released on June 4, Pew found that most Americans are still largely ignorant of Giuliani's stance on abortion.

"Because this whole issue had come to our attention, the respondents were specifically asked if they knew Giuliani's position on abortion. Some did, but the larger portion didn't," says John C. Green, a senior fellow at the Pew Forum for Religion and Public Life. "From the point of view of ordinary people, we're really early in the process right now, and it's not surprising that people don't know important facts about the candidate yet."

Some evangelical leaders feel they already know enough. James Dobson, head of the influential social conservative organization Focus on the Family, has said he would not support Giuliani. So has Tony Perkins, of the Family Research Council. In April 2006, the Rev Jerry Falwell made similar pronouncements. Shortly before his death, though, he appeared to have come around on the issue, saying, "If we have to hold our nose and vote for somebody to keep Clinton out of the White House, we have to do it." But perhaps most vociferous in his opposition has been Dr. Richard Land, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, a 16.4-million-member group that is the largest Protestant organization in the country.

"I wouldn't even consider voting for him," Land said in an interview Tuesday. And for Land, it's about more than abortion: It's about Giuliani's rocky personal history, including two divorces. Land, who has recently made supportive statements about Thompson, says he believes Giuliani's support among evangelicals has mostly come out of a sense of pragmatism, a fear of Democratic Sen. Hillary Clinton becoming the next president and a desire to see the most electable candidate become the Republican nominee.

"Once a conservative pro-life candidate passes the threshold of electability," Land says, "evangelical voters will drop from him like fleas off a dead dog." Land also warns that the nomination of Giuliani would spell trouble for the Republicans in the general election. "One thing I don't think the high muckety-mucks of the party think about, and they should, is that as long as the pro-life issue is on the table, it sucks most of the oxygen out of the other issues," he said.

Charles Dunn, the dean of Regent's Robertson School of Government, thinks otherwise. He divides the evangelical leadership into two camps, "purists" like Dobson and Land, and "pragmatists" like Robertson. And he thinks the pragmatists will win this fight. "What I'm sensing in the rank and file on this," Dunn says, "in the evangelical Christian and conservative Catholic audiences, is that you have a high percentage of pragmatists among them, and they're willing to give Giuliani a serious look."

"I was impressed," Regent student Chuck Slemp, said of Giuliani's appearance. "He came off as a strong leader, a great speaker -- very Reaganesque at times."

"I don't expect to have a president who agrees with me on everything," said another, Stephen Raper, who also praised Giuliani for "[exemplifying] his strong points" and said he was concerned about social issues, but about other things as well. Slemp agreed. "It's about the whole picture," he said.

Shares