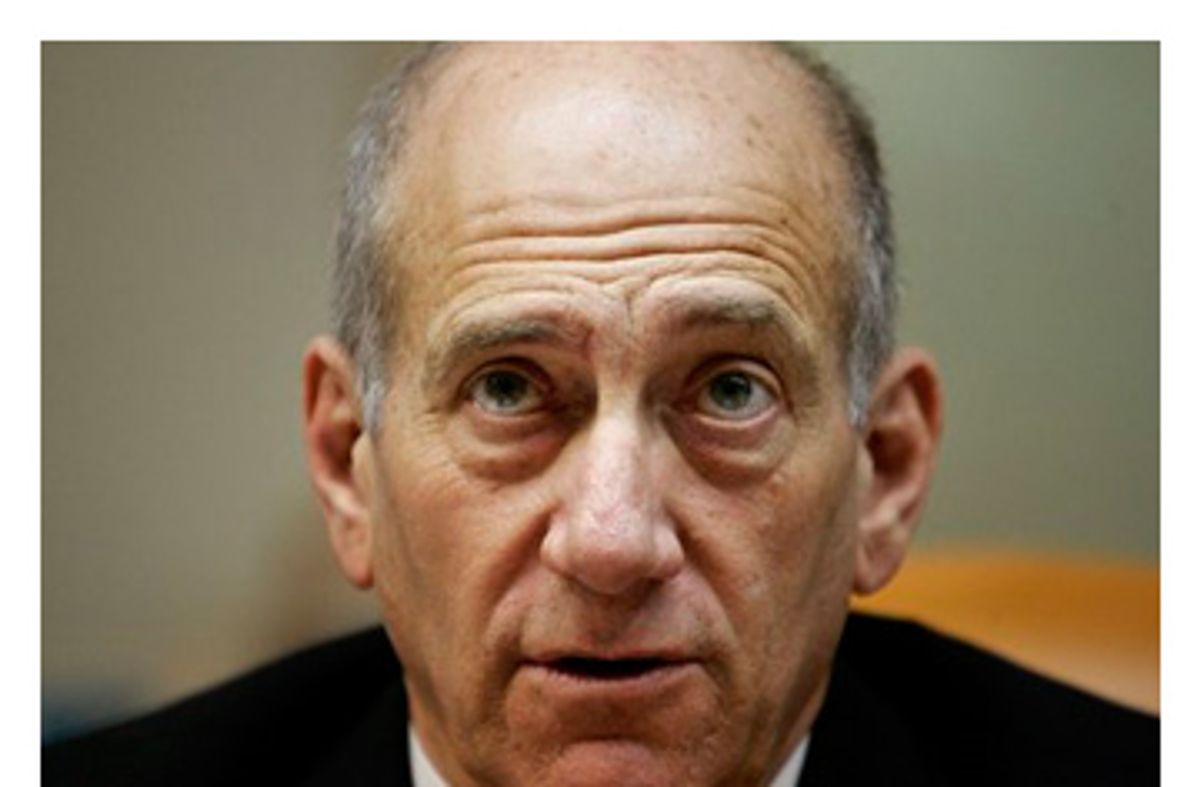

For weeks now the government of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert has been trying to assess exactly what Hamas' takeover of Gaza and the ensuing chaos mean for Israel. This is just the latest difficulty in the prime minister's rocky tenure. Since he took over for Ariel Sharon in January 2006, there have been the election of the militant Hamas government, a total breakdown in the peace process, the kidnapping of Israeli soldiers, a barrage of rocket attacks on Israeli cities, rising tensions with Iran, and last summer's disastrous war with the Hezbollah, for which Olmert was later brutally criticized by a government commission. His detractors emphasize that Olmert failed to secure the release of the kidnapped Israeli soldiers and crush Hezbollah, and that he has failed to make any progress toward an agreement with the Palestinians. The Israeli public appears to have overwhelmingly lost faith in his leadership; a recent poll showed his public approval rating at a mere 3 percent, absurdly low even in Israeli politics.

It's not surprising, then, that foreign and Israeli observers have been predicting the imminent demise of the Olmert government for some time now, and it may indeed seem that he is hanging on to power by the thinnest of threads. But if you're waiting for Ehud Olmert to slip off into the night, don't hold your breath. Despite his abysmal approval ratings and the multitude of fingers pointed at him, Olmert may in fact be in the strongest position he has been in for more than a year. Drawing on lessons learned from his predecessor, Sharon, Olmert is one of the shrewdest political operators in Israeli politics, and it appears that he has managed to lock down his position in the prime minister's office until at least next year -- which, on the Israeli political timescale, is an eternity.

Overshadowed by the awful mess in Gaza is the recent transfusion of new life into the government. On June 18, former Prime Minister Ehud Barak was appointed defense minister, providing a shot of adrenaline to the Olmert government by deflating criticism that it lacks the security credentials so crucial in Israeli politics. Neither Olmert nor his former defense minister, Amir Peretz, have a military background, and bringing in Barak -- the former chief of staff of the military, and the most decorated officer in the history of Israel -- adds badly needed military know-how and a sense of gravitas to Olmert's administration.

In addition, the two Ehuds are old friends, a stark difference from Olmert's relationship with the ousted Peretz, who was also savaged by critics in the wake of last summer's war. According to officials in the prime minister's office and elsewhere in the government with whom I have recently spoken, Olmert and Peretz would go for days without conversing with each other. When the two most important figures in the administration behave in this manner, it only underscores why the Israeli public has little trust in its current leadership. But with Barak as defense minister, the cohesion and confidence needed to deal with threats such as Iran or the Gaza situation are much more credibly in place.

Barak's appointment is not the only political development providing renewed vigor to Olmert's grip on power. On July 15, Shimon Peres will become Israel's new president -- a largely symbolic role, but one with much visibility. Peres is another Olmert friend, also hailing from the Kadima Party to which Olmert belongs, and Peres' election to the presidency has been seen as a victory for the prime minister. Because of the respect Peres commands among leaders around the world -- if far less so among the Israeli public itself -- he will likely serve as a global emissary for Olmert, helping to foster support for Olmert's diplomatic policies in the capital cities of Europe, the United States, and even in the Arab world. In reflecting on the twin victories of Barak and Peres, more than one Israeli commentator has referred to this as the dawning of a "second Olmert government."

This leadership shuffle also serves to thwart some of Olmert's political rivals from capitalizing on his lack of popular support. As a sort of grand foreign minister, Peres will clip the wings of the actual foreign minister, Tzipi Livni, who hopes to replace Olmert and has already called for his resignation. And by appointing Barak, Olmert has managed to sideline his arch-rival, Benjamin Netanyahu, the leader of the right-wing Likud Party who has been hoping to overcome Olmert on a hard-line security platform. Olmert has also managed to deflate criticism from the far right by including the hard-line Yisrael Beiteinu Party in his ragtag coalition. In essence, Olmert has managed to clear any serious near-term political challengers from the field.

Most analysts agree that the developments in Gaza are ominous for Israel and the region in the longer term, but from a cynical point of view, even the Hamas takeover there has been something of a boon to Olmert's position. With Hamas ruling despotically over what appears to be a miniature failed state, it is easier for Olmert to throw up his hands and say that it is impossible at present to negotiate with the Palestinians. This allows him to resist American and international pressure to move toward an agreement. Although Condoleezza Rice's State Department has again been gently pushing him to make some concessions, the current situation allows Olmert implicitly to align himself with the intransigent views of Vice President Dick Cheney, which lets Olmert avoid upsetting his right-wing Israeli political allies by engaging in any potentially risky diplomatic initiatives.

Olmert may be taking some cues from the example of his wily mentor, Ariel Sharon, who was a master at political maneuvering and holding on to power. Whereas Olmert came into office with grand pronouncements about new policies and spoke to the media frequently to explain them, the tone of his leadership lately has shifted to a more Sharon-like ambiguity. He is less readily available to the media than before and far more prone to making cryptic statements, such as the mixed signals he has been giving regarding the possibility of peace talks with Syria. It is harder to know what he is thinking and what he is planning to do -- and thus harder for his rivals to unseat him. Even his handy assembly of an ideologically diverse coalition and crafty maneuvering to block the aspirations of his opponents are lessons learned in the shadow of Sharon.

To be sure, this could all change tomorrow. Such is the nature of the Middle East and of Israeli politics in particular. Another war with Hezbollah could erupt, as could a war with Syria -- which some analysts are predicting in the near future, and which could be even more earth-shattering and calamitous. In addition, there is the possibility of an Israeli or American strike on Iran over its nuclear program, which would potentially roil the whole region.

A new political explosion in Israel could also disrupt Olmert's momentum. Toward the end of this year, for instance, the commission tasked with investigating the conduct of last summer's war will release its final report. It is hard to imagine, however, that it will be much more scathing than the interim report already issued, which heaped blame on the prime minister -- and from which he was able to walk away relatively unhurt. Ironically, what may be more problematic for Olmert will be Defense Minister Barak's reaction to the report. Barak has made no secret of his own desire to eventually regain the premiership, and although he is an Olmert ally at the moment, the release of the report could easily spark the beginning of his own campaign to unseat his friend and take his place. Right now Barak is a tremendous asset to Olmert, but in the long term his presence and power are a ticking bomb. Israeli politics is a blood sport, and friendship only goes so far.

In spite of these potential pitfalls, Olmert has positioned himself to survive at least until 2008 and potentially even for another year. That may not seem a long time, but in the ever-shifting sands of the Israeli political arena it is a significant chunk of time. Whether any of this is actually good for Israel, for the Palestinians, or for American interests in the region is a question for another day. But for the moment, everything's coming up Olmert.

Shares