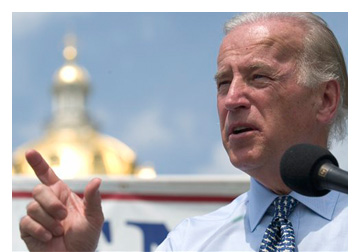

Dressed Iowa casual in a blue blazer and open-necked blue shirt, Joe Biden had been answering questions at the Phoenix Cafe for about 20 minutes Tuesday when his host, state Rep. Eric Palmer, broke in with an urgent message. “Sorry to interrupt,” Palmer said, “but your staff thinks that you need to leave.” Looking hungrily out at the lunchtime crowd of 75 Democrats, almost all of whom will participate in the opening-gun caucuses next January, Biden cracked, “But they don’t vote.”

The next question, about his asterisk-level standing in the polls and his anemic fundraising, may have prompted Biden to wonder why he had lingered. But rather than decry the horse-race surveys or make excuses for the paltry $2.4 million he collected in the second quarter (sixth place in the Democratic money marathon), the six-term Delaware senator made his anything-can-happen argument with the aid of a potent audience-participation experiment.

Biden simply asked, “How many of you think that the majority of the people in Iowa have firmly made up their mind about how they will vote in the caucuses?” Not a single hand was raised, demonstrating that most Iowans recognize how shallow are the sentiments reflected in the polls.

First elected to the Senate in 1972 at age 29 (three weeks before he was constitutionally eligible to serve), Biden has always seen himself as a smart, hardworking, glad-handing East Coast politician with a gift for Irish blarney and charm. When he made an abortive bid for president in 1987, Biden now admits, “I was focused on my conviction that I was a better candidate than the other people — and not that I was ready to lead the country.”

But as the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden is now in the curious position of running for president as the long-shot candidate with substance, while Barack Obama, John Edwards (some days) and Hillary Clinton (by marriage) outshine him in the megawatt, star-search spotlight. The self-made senator, who graduated from the University of Delaware with a C average, can only triumph if experience ends up mattering more than excitement. As Biden explained in his stump speech in Grinnell, simultaneously sounding boastful and aw-shucks embarrassed, “I know most every one of these world leaders by their first name. It’s not because I’m important … I was a kid coming up when they were coming up.”

From his perch at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, or possibly as a Democratic secretary of state (his likely job had John Kerry been elected) or as president, Biden may yet play a central role as America grapples with the never-ending nightmare that is Iraq. Biden, along with his fellow Sens. Clinton, Edwards and Chris Dodd, voted for the 2002 resolution permitting Bush to launch the war. During a 2005 interview with me, Biden recanted his vote, saying, “I never figured on the absolute incompetence of the administration … If I knew Cheney and Rumsfeld so wholly possessed the president’s attention, I never would have voted for that.”

Unlike his rivals for the nomination, Biden has been championing a plan (which he proposed last year with Leslie Gelb, the former president of the Council on Foreign Relations) to subdivide Iraq along ethnic lines within a federal system. (The plan for separate Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish regions is explained in detail on Biden’s campaign Web site.)

But these days, Biden acknowledges that it may soon be too late to salvage anything from the debacle in Iraq. During an interview Tuesday along the Iowa campaign trail, Biden talked bluntly between stops about the dire alternatives facing the man he imagines will be the next president: “I may be left on Jan. 20, 2009, with no option but to withdraw and to contain [the civil war within Iraq]. To literally have inherited a fractured country … where there is no way to put Humpty-Dumpty back together.”

During one conversation in the campaign van headed into Grinnell, Biden found himself torn between holding a cup of coffee and gesturing with both hands. Confronted with a classic unwinnable situation, he carefully put the coffee cup on the floor. There is a bluntness to Biden, which stands in contrast to a candidate like Clinton, who seems to mentally convene a focus group before answering a question.

But Biden can also be impolitic in his criticisms of immediate-withdrawal-for-Iraq political grandstanding, and the bloggers who encourage it. “I don’t believe that this sort of red-meat, ‘I’ll get out quicker than the other guy’ [competition] has resonance,” he said, adding that in political terms for the Democrats, “I think it has a real danger.” Biden, who has endured 22 years of Republican presidents while in the Senate, criticized bloggers’ vow to “take back” the party. “They don’t own the Democratic Party. What are they talking about?”

No antiwar stance arouses Biden’s ire like Bill Richardson’s hyperbolic claim that he alone of the major Democratic presidential contenders would leave no residual forces in Iraq. As Biden put it, “Governor Richardson, God love him, says that he is the only one who is going to get out entirely, but he is going to leave enough forces to protect our embassy. He ought to talk to the Marines; they say that’s 10,000 troops.”

There is a free-form quality to Biden’s stump speeches as arguments appear from nowhere, presumably because something occurred to the candidate, and then disappear from the repertoire for the rest of the day. Tuesday morning in Cedar Rapids talking to 100 Democrats (a good-size crowd for Iowa in the days before Obama mania and two Clintons campaigning together) at the Blue Strawberry Coffee Co., Biden battled the roar of the espresso machine as he tried to explain a controversial recent vote in the Senate.

Alone among the Democratic presidential contenders, Biden voted for Iraq war appropriations, even though the final legislation did not contain a timetable for withdrawal. Alluding to that vote, he said, “If there is a single solitary troop left in Iraq, we must protect that troop. We have a moral obligation to protect these kids we send … We need 67 votes to overcome the president’s veto. We can cast all the symbolic votes we want. But the bottom line is that I’m not trading symbolism for lives.”

As a presidential candidate, Biden lives in a world seemingly free from fear about how his words will appear out of context. Back in January, as he was launching his presidential campaign, Biden stumbled badly in an interview in which he described Obama as “clean” and “articulate.”

But even now, Biden cannot resist flirting with rhetorical danger. In Cedar Rapids, he borrowed a catchphrase from an anti-integration 1968 third-party candidate while discussing the healthcare plans of his rivals: “As old George Wallace used to say 40 years ago, ‘There ain’t a dime’s worth of difference between our plans.'” Two minutes later, talking about an idea for African debt relief that he had suggested to Bono, Biden said humbly, “It’s not Al Gore inventing the Internet.”

That one even registered on Biden’s internal danger meter, as he realized that there are worse political dangers than appearing immodest. Walking over to me, the only national political reporter in view, Biden loudly insisted, to the delight of the crowd, “It’s real, real clear that I didn’t say that.”

Moments like this, Biden conceded in our interview, represent the downside “of my being straightforward and candid … I’m going to get myself into trouble.” Then Biden, who was already in the Senate as Obama was just getting ready for middle school, said, “I can’t start to calibrate all this stuff … The public in the primaries, as well as the general election, are going to judge me for all of who I am.”

And for Joe Biden — the candidate who never stops talking, but often has much to say — the inherent contradiction is between his still youthful irreverence and the hard-won gravity that comes with the chairmanship of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and watching America go so tragically awry abroad.