When Steve Jobs, Apple’s CEO, unveiled the iPhone, he promised it would put “the Internet in your pocket for the first time ever.” So a few days after purchasing this wonder, I was walking around town when I had a delightful epiphany: Hey, now that I’ve got the Internet in my pocket, I can listen to a live stream of NPR anytime I want! (I’m a fellow of milquetoast impulses.) A quarter-second later the truth hit me. Of course I can’t get NPR on my iPhone; it lacks the necessary software. I also can’t watch Comedy Central’s online videos, nor buy a song from iTunes, nor place a Skype call. Jobs is right; the iPhone is the Internet in your pocket, and at times, having it there feels marvelous. But often the device is a tease: Because Apple and AT&T have locked it down, the iPhone gives you the Internet of 1996, not of 2007. You can look but you can’t watch, listen, download or play.

When Steve Jobs, Apple’s CEO, unveiled the iPhone, he promised it would put “the Internet in your pocket for the first time ever.” So a few days after purchasing this wonder, I was walking around town when I had a delightful epiphany: Hey, now that I’ve got the Internet in my pocket, I can listen to a live stream of NPR anytime I want! (I’m a fellow of milquetoast impulses.) A quarter-second later the truth hit me. Of course I can’t get NPR on my iPhone; it lacks the necessary software. I also can’t watch Comedy Central’s online videos, nor buy a song from iTunes, nor place a Skype call. Jobs is right; the iPhone is the Internet in your pocket, and at times, having it there feels marvelous. But often the device is a tease: Because Apple and AT&T have locked it down, the iPhone gives you the Internet of 1996, not of 2007. You can look but you can’t watch, listen, download or play.

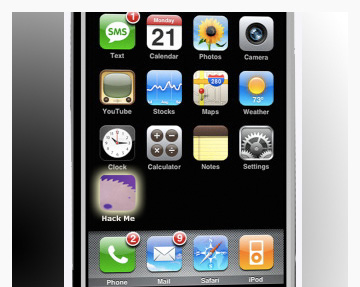

In my first review of the iPhone, which I wrote just hours after laying my hands on the thing, I fingered the lockdown as my biggest complaint. Now, a week and a half later, my feelings haven’t changed. What has changed is the context. Quickly and assuredly, a distributed crew of determined hackers is breaking down the iPhone’s walls. They have managed, so far, to use the iPhone’s iPod and Wi-Fi Internet functions without first signing up to AT&T, and they’ve also accessed the phone’s “file system” — letting them add ring tones and wallpaper, and play with the phone’s menu bar.

Over the past few days, I’ve been talking to several of these hackers. They report amazing progress at freeing the iPhone — what they call escaping the iPhone jail. They say they’re about to release a programming “toolchain” that will push them toward their primary goal in a matter of weeks, if not days. That first goal: to unlock the iPhone from AT&T, allowing people to use all of its functions on any compatible cell network in the world.

“We’re quite close,” says GJ, who called me up after I posted a notice on Hackintosh looking to talk to some of the coders who are cracking open the iPhone. Like all the others I spoke to, he wouldn’t give me his full name nor much real-world identifying information, but he was quite willing to discuss the group’s iPhone hacking efforts. “The phone has got to communicate with the cellular network somehow, and we’ve found that the radio hardware in the iPhone is actually quite common in the industry,” GJ says. “So we know how to get the radio to talk to the cell tower. What we don’t understand is how to interact with the radio from the iPhone and to unlock it. But we’re quite close.” The hack, he says, will most likely work through software — you’ll download a file, patch your iPhone while it’s connected to your computer, and then, like that, you’ll be able to use it with another network.

GJ and others believe that unlocking the phone from AT&T is a first step toward unlocking it generally — that is, toward making it a platform for which developers across the world, rather than just the developers at Apple, can build useful applications. The iPhone uses a cellular system known as GSM; in the U.S., T-Mobile is the only other big network that can carry its signals. (Verizon and Sprint use an incompatible cell standard called CDMA.)

But GSM is the most popular wireless standard in the world, and hackers predict that if they unlock the iPhone, early adopters in Europe and Asia — where the phone has not yet been released — would flock to purchase it. And then they too would begin to tinker with it. “By unlocking the platform we are essentially opening the flood gates and ‘letting it all in,'” a hacker named Jorge told me in an e-mail message. Conceivably, one of these people could figure out a way to write programs for the phone — and perhaps, then, to let me stream “All Things Considered.”

Several loosely affiliated groups are now working to decouple the phone from AT&T. I’ve been following the largest and most promising of these, the crew that congregates on #iPhone, a chat room that you can get to using the Internet Relay Chat system on the server irc.osx86.hu. At any given time, about 400 people are on the channel, but only about 30 are working full-time on the hack. They’re a diverse bunch, spread throughout the U.S. and Europe and bringing various flavors of expertise — in coding, in cell system design, in old-fashioned operating-system breaking and entering — to the effort. They’re working more or less nonstop, digging, like miners in an unchartered hole, at all of the iPhone’s hidden caves, in search of a rich vein.

It’s a tedious process, one that sometimes leads down dead ends. Over the weekend an American teenager who goes by the handle geohot stayed up all night soldering the connections on his iPhone dock in order to create a direct, “serial interface” to the phone.

He succeeded. By the morning, in what seemed like a major breakthrough, he had found a way to issue commands to a key part of the system known as the bootloader. Some in the team thought they’d reached the holy grail; all they’d have to do was issue the correct commands to the iPhone’s radio and it would be free. But that didn’t work. Many of the commands that the hackers sent to the bootloader came back with “permission denied” errors. Apple, they found, had protected the bootloader cryptographically, meaning that to do anything useful with it, they needed Apple’s secret password. They had to find another way.

Since then the hackers have been looking to build a toolchain, a programming interface to work with the iPhone’s file format (called Mach-O) and processor type (known as ARM). This has been a difficult coding task, one that only a handful of them know how to do — but today they told me that they’re very nearly done with it. And once they have that, unlocking the phone could be around the corner.

Hurdles, though, may persist. Even if the hackers manage to break the phone free from AT&T, getting it to run non-Apple-approved programs may be much more difficult. The hackers don’t have the programming tools that Apple does, and, moreover, it’s unclear if they can get around Apple’s cryptographic locks on the phone.

They’ve also faced the problem of defectors: “A couple people have jumped ship and see the possibility of making a profit,” Jorge told me. One member of the group managed to build customized ring tones into the iPhone three days ago, he said, “but this person held out on us thinking he was going to be able to sell a service.”

A more serious threat may come from AT&T and Apple. If hackers unlock the iPhone tomorrow, Apple could lock it back up next week, and then the group might have to start all over again. They could also, of course, face legal threats. I asked Apple and AT&T if people who hacked their iPhones were breaking any rules. Apple did not respond; AT&T did.

“The iPhone explicitly requires customers to sign up with AT&T when they buy the device,” Susan McCain, a spokeswoman, told me in an e-mail. Anyone who buys the iPhone and doesn’t use AT&T is engaging in an “illegitimate use” of the phone, another AT&T representative, Mark Siegel, told the Wall Street Journal.

Though this certainly makes economic sense — AT&T has a lot riding on iPhone exclusivity — it seems a crazy policy for Apple to have signed on to. “I look at it and I’m like, Guys, what were you thinking?” GJ says. “We’re in an age where people want to be able to build our own technology. We’re becoming a culture of experimenters. And I think it’s a little unfortunate that companies have decided to take this stand against us.”