John McCain’s 2008 Straight Talk Express, a runaway train threatening to jump the tracks, lost its conductor, engineer, brakeman and flagman Tuesday, as four of the campaign’s top advisors submitted their resignations after months of declining poll numbers, high spending and anemic fundraising.

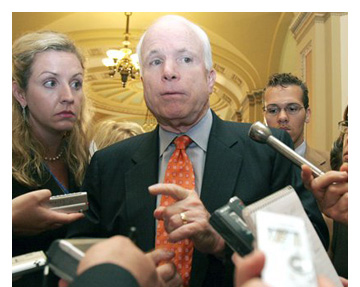

A few hours later, McCain appeared on the Senate floor in a bright orange tie to offer a public show of determination in the face of dismal news. “A lot of us are not driven by polls. A lot of us are driven by principle,” he said, before raising his voice. “And a lot of us do what is right, no matter what the polls say.”

He was speaking about his support for the war in Iraq, but his comments could have applied just as well to his Republican presidential campaign. As recently as this spring, the McCain campaign was still running as the inevitable inheritor of the party mantle, with an enormous campaign operation that spanned all the early voting states burning up more than $22 million in just six months. Every time he spoke to the press, John Weaver, McCain’s senior political strategist, tried to create an aura of inevitability around the candidate. “We wouldn’t trade places with anybody,” he told reporters, over and over again.

But that strategy — to cast McCain as the unassailable front-runner — only highlighted McCain’s weaknesses, by setting expectations wildly high. Even before the campaign began, the Arizona senator had alienated many of the Republican Party’s bankrollers by supporting campaign finance reform and aggressive investigations into corporate wrongdoing and the convicted lobbyist Jack Abramoff. Despite the occasional olive branch to pastors like the late Jerry Falwell, he refused to kowtow to the Republican Party’s evangelical base. And, perhaps most important, he found himself on the wrong side of a midsummer grass-roots revolt by Republicans who were infuriated by the immigration reform bill, which McCain helped author.

Last week, with only $2 million in the bank, McCain’s two senior advisors acknowledged their faltering strategy in a conference call with reporters. “At one point, we believed that we would raise over $100 million during this calendar year, and we constructed a campaign based on that assumption,” said Terry Nelson, the campaign’s manager. “We believe today that that assumption is not correct.” Weaver also appeared on the call to assure everyone that “we’re very pleased with where we are structurally.”

On Tuesday, both Weaver and Nelson announced their resignations. At the same time, Rob Jesmer, McCain’s second political director in three months, and Reed Galen, the deputy campaign manager, also quit. Mark Salter, a close McCain confidant, decided that he would take a reduced, unpaid role in the campaign. Of McCain’s innermost circle at the campaign, only Rick Davis, the manager of McCain’s 2000 campaign, remains. “Today we are moving forward with John’s optimistic vision for our country’s future,” Davis said in a statement, on a day that is sure to make McCain’s supporters feel pessimistic. McCain’s campaign spokesman and former Nelson protégé Danny Diaz also tried to peddle a shiny outlook on the day’s events. “Both Terry and John put McCain first today,” he said.

The news for McCain may be even more grim in the early primary states, where the campaign has pinned its hopes of victory. The issue of immigration has proved to be particularly potent in Iowa and South Carolina, where McCain has been forced to cut his staff by more than half. The campaign already decided to bow out of the symbolic Iowa straw poll in August, joining Rudy Giuliani and the putative candidate Fred Thompson in upsetting the local Republican Party.

But the turmoil at the campaign’s headquarters in Crystal City, Va., is not necessarily a death knell for McCain’s presidential ambitions, and he could still be a formidable candidate. He has raised more money than all but two other Republicans, Giuliani and Mitt Romney, and he still polls in the top three nationwide, and in the top four in the early voting states of Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina. Early Tuesday evening, McCain held a 30-minute conference call with his top New Hampshire supporters. “It was all very upbeat,” said Peter Spaulding, who chairs McCain’s campaign in the Granite State. “The average person up here doesn’t know who is running the campaign.”

McCain’s personal and political story line may also find more traction once he returns to the more familiar role of maverick outsider. Like John Kerry, another Vietnam veteran who was all but written off in the months before the first votes were cast in 2003, John McCain still has time to recover. On Iraq, he’s been the most prominent supporter of Bush’s so-called surge plan, and while that may prove a liability in the general election, there’s no indication that his outspoken position is hurting him among Republican primary voters.

Perhaps the biggest question raised by the resignations is how well McCain will weather the loss of Weaver, who has been to McCain what Karl Rove is to George W. Bush, a political mastermind and guide. A hunched and quiet man, Weaver helped design McCain’s 2000 primary victory in New Hampshire, and has remained McCain’s traveling companion on the campaign trail all year.

Weaver’s ties with McCain date back to the star-crossed 1996 Phil Gramm presidential campaign, when the Arizona senator served as Gramm’s national chairman. As a top advisor to Gramm, Weaver helped construct a campaign that had an uncanny resemblance to the 2008 McCain operation. Gramm began the campaign by proclaiming that he had “the most reliable friend that you can have in politics — ready money.” And then Gramm, who dropped out of the race after finishing an embarrassing fifth in the Iowa caucuses, proceeded to squander almost $20 million on a bloated staff and oversize campaign infrastructure before a single primary vote was cast.

This weekend McCain has scheduled a campaign trip to New Hampshire, the scene of his jaw-dropping 19-point blowout victory in 2000 against George W. Bush. If the McCain train can pull out of the station again, this is where it will happen. If he can recover, this is the time to start. “Now is not the time to be timid or to shy away from our challenges,” McCain wrote to supporters in an e-mail sent late Tuesday afternoon. “Now is the time to stand up and say what we believe.”