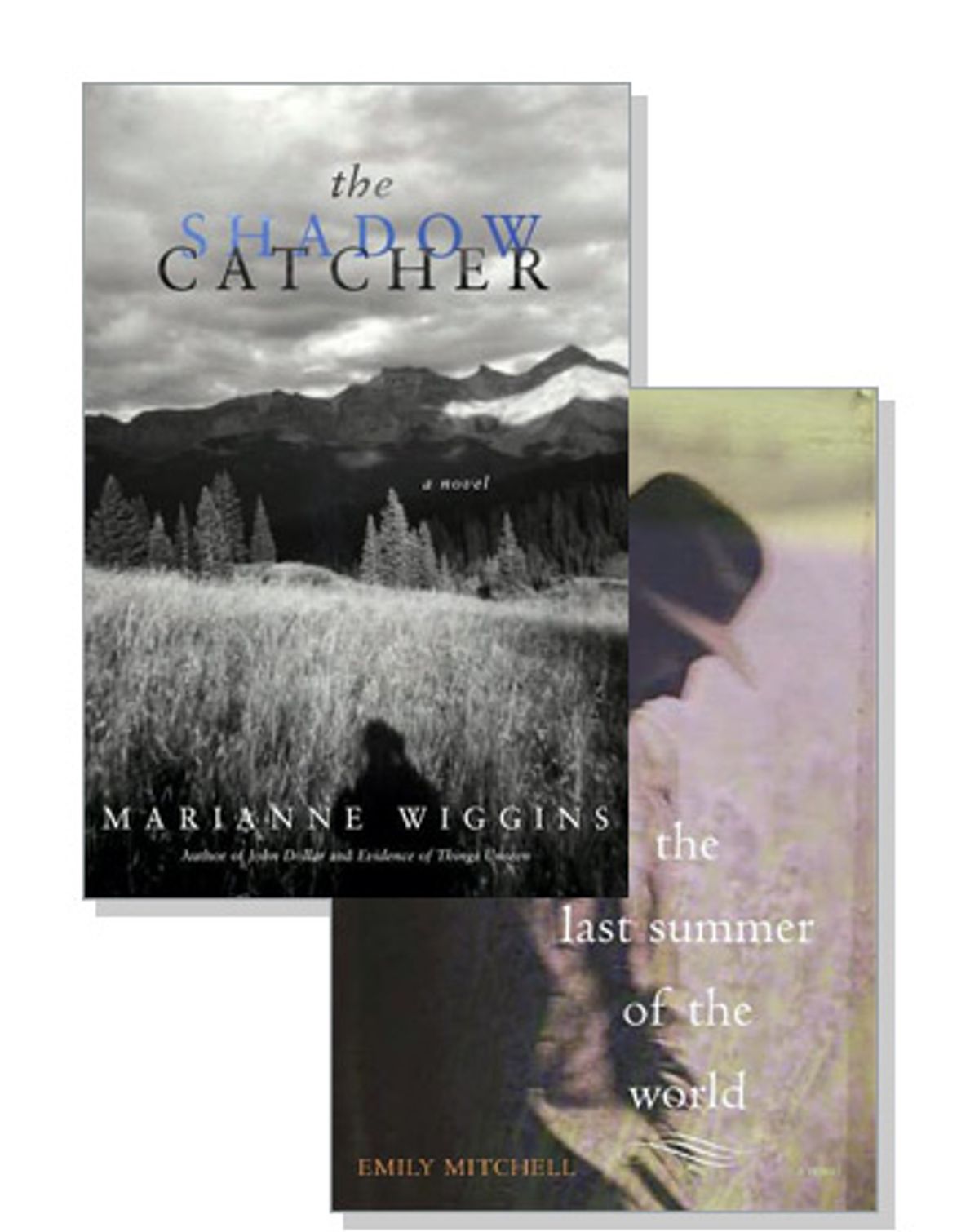

The most fascinating person in any given photograph is usually the one whose face is cut off, out of focus or turned away. We can smile and say cheese all we like, but it's these mistakes, the shots snapped a half-second too late, that truly reveal, hinting at the unguarded lives beyond the frame. Two new novels -- "The Shadow Catcher," by Marianne Wiggins, and "The Last Summer of the World," a debut by Emily Mitchell -- zoom in on this periphery to explain and expand on the lives and loves of two of photographic history's most complicated and compelling characters, Edward Curtis and Edward Steichen.

Like photographers, both Wiggins and Mitchell have chosen their subjects deliberately and staged their dramas with care, embroidering known history by promoting wives, lovers, mothers, sisters, colleagues and other walk-on characters to leading roles. But at the center of each of their tales is a solitary man, a cipher of sorts, who expresses himself most sensitively through the images he produces. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, both "The Last Summer" and "The Shadow Catcher" are also cluttered with the clichéd debris of masculine creativity -- the abandoned children and aggrieved wives, the epic visions, egos and doubts.

We have long since given up on the idea that photographs serve up impartial truths and embraced them as art. But is it any less naive to believe we can glean a glimpse of the men behind the lens by looking at what they placed in front of it? Of the two novelists, Wiggins makes the most impassioned case for trying. In "The Shadow Catcher," when Clara, the young woman who will become Edward Curtis' wife, first happens upon his photographs hidden away in a barn darkroom, she shudders with sudden insight: "The photographer was acting for you with his eyes, acting as your own eyes would. It was a contract between the artist and the viewer that few painters could make, and it was deeply personal, she saw, because she could not look at any photograph of Edward's without thinking about Edward, himself, about the man behind the camera, about how and why he had positioned himself where he had."

Still, readers who come to "The Shadow Catcher" expecting a linear biography of the "man behind the camera" will be sorely disappointed. Instead, the author weaves vignettes from Clara and Edward Curtis' stormy courtship and divorce with a magical-realism-tinged meta-narration told by "Marianne Wiggins," a Los Angeles screenwriter with some lost-daddy issues of her own, who is trying to sell -- you guessed it -- a script based on her novel about Edward Curtis.

As a plot device, Wiggins' fictive alter ego teeters between inspiration and affectation, but it works most nimbly when the author uses (the fictive) Wiggins to challenge the romanticized myth of Curtis' life, and draw out a thornier, more authentic truth. No one is off limits from Wiggins' skepticism, including the Hollywood film industry, which comes in for a memorable bit of skewering in an opening scene between Wiggins, her agent and a producer, in which the first, and most vital, questions asked about Curtis (now, the potential movie hero) are: How tall was he and did he have blue eyes? (The answers: 6 feet; yes.)

Most people know Curtis (1868-1952) as the visionary behind "The North American Indian," a 20-volume photographic chronicle of what he dubbed the "vanishing races" of the cowboys-and-Indians-era West; even today, his images are a staple of the Americana poster and postcard trade, praised earnestly for the melancholy "dignity" of their subjects' deeply lined native faces. But "The Shadow Catcher" does not concern itself with that Curtis. Wiggins is fond of the John Ford line, "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend" -- but her instincts seem quite the opposite. Instead (both as author and meta-narrator), Wiggins stalks the character behind the camera, chasing after the facts Curtis has left out of his frame.

"The Shadow Catcher" is no biography; it is a quest, across years and state lines, and through her own meta-narrator's life, for the real Curtis and the manifest-destined, road-wandering, lost fathers like him, who have been obscured beneath a sentimentalized and shellacked American myth.

Luckily for all of us, that story is richer than any Oscar-hungry Hollywood biopic, and reveals as much about the flawed nature of photography as it does about the fallible hearts of men. The secret truth behind Curtis' photographs is that despite their grave beauty, they are essentially fictions: born out of a rebellious spirit of frontier adventure, yes, but also funded by J.P. Morgan and other titans of big business. And though they purport to capture the "last days" of America's great wandering clans, Curtis' images were not shot in the mid-19th century as they might appear, but early in the 20th, years after the railroads and the government had forced Native Americans onto reservations, when their tribes were not so much "vanishing" as atrophying. To service this theatrical vision, Curtis was not above dressing his subjects in apocryphal costumes or staging his scenes so that cars, clocks, waistcoats -- and any other giveaway of modernity -- were obscured or eliminated just outside the frame.

Wiggins' assessment is blunt: "[Curtis' photos] are beautiful to look at. But they're lies. They're propaganda." And ultimately, the mythos they fuel is not just the lie of the elusive American West, but also the fiction of the photographer as the sympathetic romantic visionary, that perfect marriage of modern technology and soul.

Though he did not shoot the great West, Edward Steichen, the photographer at the center of Emily Mitchell's debut novel, "The Last Summer of the World," was equally influenced, and ultimately defined, by the era in which he lived and worked. Like a European, lost-generation equivalent of Curtis, Steichen was a prodigious image maker and precocious success story -- as well as a rumored philanderer and absent father.

The bullet points of his story are well known: Steichen climbed the ranks of the early 20th century art world alongside luminaries like Auguste Rodin and Gertrude Stein, along the way founding the photo-secessionist movement with Alfred Stieglitz, and becoming a curator of photography for the Museum of Modern Art, where he staged the immense and groundbreaking exhibit "The Family of Man" in 1955.

While Steichen's life offers a full catalog of characters and dramas, Mitchell wisely chooses to focus in on some of his biography's richest, and least traveled, terrain: the summer of 1918, in the thick of the First World War, when Steichen was stationed in France, serving as a reconnaissance photographer. Indeed, the grim routine of the Great War provides Mitchell's story with a precise, sober backdrop that makes Wiggins' expressionistic wanderings feel downright hyperactive.

Mitchell's readers first encounter Steichen after he has been accused of adultery, stripped of his home and children, and watched his wife (also, coincidentally, named Clara) sue his alleged mistress for alienation of affection. Like Wiggins, Mitchell employs her protagonist's photographs as a stylistic device, heading alternate chapters with titles from his real body of work and using those photographs as the Rorschach tests from which she spins speculative narratives. Though some of those scenes feel a bit calculated and pat (must we really witness Auguste Rodin humping his mistress on a studio floor and hear him expound on the "needs of the body"?), for the most part, Mitchell exhibits admirable restraint as she interweaves contemporary scenes from Steichen's soldier life with his awakening as an artist and his romance and unraveling marriage to Clara.

When their story begins, Clara has fled their idyllic home in the French countryside and returned to America. Longing for escape and desperate to make his craft have meaning in an upside-down world, Steichen has joined the war effort -- but any hope for escape from his troubled past becomes plainly impossible as soon he finds out that his accused mistress is also on the front, having returned to work as a nurse.

Despite the careful mythology built up around these not exactly fictional heroes, it is once again the peripheral characters -- the wives, the war and, especially, the photographs themselves -- that deliver the most persuasive insights and emotional wallops in both novels. How is it that two men of such penetrating vision can remain so elusive themselves? It may be that, when working with photography, the real, everyday present of artists' lives is eclipsed by the allure of the frozen past.

Mitchell hints at that possibility through a frequent and dramatic use of flashbacks, each of which unfolds like a photograph enchanted into life. In "The Last Summer of the World," Steichen's present is peopled with broken soldiers and broken hearts, but in the past world of his photographs, his friends are vital, his country is peaceful, and his family is intact. The characters of Edward and Clara are increasingly constructed out of the flickers we see of their former selves. Who is more real, the happy maiden behind the piano, eyes still filled with flirtatious admiration for her ambitious young love, or the wife who stands in a disarrayed room in an old farmhouse, looking at her husband's photographs, cursing that their lives could not be so graced?

It is a mournful Clara Steichen who perhaps puts it best, when, toward the end of "The Last Summer of the World," she says of her husband's work: "Here is his vision, elaborated in hundreds of discrete moments, plucked from time and fixed on paper; here are the things he chooses to tell the world about itself. It is a beautiful vision, one in which nothing is ugly and broken, nothing dull and repetitive; the pictures he makes are of a world that can be understood and can therefore be loved without reservation. But she knows there is another version; there are things his vision omits to show."

Both Mitchell and Wiggins pay homage to works of genius, beautifully rendered, even while they (and we) remain fascinated by the men behind the memories and the lives behind the art.

Shares