Heroin, developed in 1898 by a chemist at the Bayer Laboratory in Germany, derived its name from the German "heroisch" (heroic), and despite everything we know about the horrors of heroin addiction, smack still manages to be marketed as sexy in advertising and art. Whereas "meth" rhymes with "death" and sounds like "mess": an ugly word for an ugly drug that seems unlikely to benefit from an image update anytime soon.

Even its myth of origin is tainted, deriving from a probably apocryphal story of the drug's development by Hitler's chemists to fuel a robotic, remorseless army of Nazi storm troopers. So says Frank Owen in "No Speed Limit: The Highs and Lows of Meth," his gripping sociocultural history of a substance that has demonstrated a malevolent, near-viral ability to adapt to shifts in taste, popularity, population, production and distribution.

The synthetic methamphetamine has a horticultural analog in ephedra vulgaris, used for millennia by the Chinese as an herbal remedy for asthma and other breathing ailments. In 1887, a Japanese scientist identified ephedra's active ingredient, ephedrine, a chemical similar to adrenaline. The same year, the German L. Edeleano used ephedrine as the base to create phenylisopropylamine, now known as amphetamine.

But because the substance seemed to have no useful medical applications, the malign genie remained in the bottle until the 1920s, when ephedrine was first used to treat asthma in clinical trials in North America and Europe. Meanwhile, a Japanese scientist developed a more powerful synthetic version of the drug that came to be known as methamphetamine. In 1927, a British research chemist at UCLA named Gordon Alles resynthesized Edeleano's drug for use as a bronchiodilator, and subsequently sold the formula for use as an over-the-counter inhalant.

The new drug, christened Benzedrine, was initially marketed as a miracle cure, "used to treat obesity, epilepsy, schizophrenia, cerebral palsy, hypertension, 'irritable colon,' 'caffeine mania,' and even hiccups." By the 1950s, variations on its chemical theme included Dexedrine, whose "gentle stimulation will provide the patient with a new cheerfulness, optimism, and feeling of well-being"; Norodin, "useful in reducing the desire for food"; Desoxyn, for "When she's ushered by temptation"; and Syndrox, "For the patient who is all flesh and no will power."

All these testimonials originated in medical journals, and the drugs were targeted at women, mostly as "pick-me-ups" and diet aids. But even prior to the 1950s, amphetamine and methamphetamine had begun to leave their mark upon the American heartland. During World War II, factories at the San Diego naval base provided troops overseas with Benzedrine. Owen claims "GIs consumed an estimated 200 million pills," causing untold numbers of soldiers to return stateside with an amphetamine habit.

After the war, some former servicemen took jobs in Southern California's defense plants, where amphetamines' "ability to make boring and repetitive mechanical work seem fascinating and meaningful" no doubt came in handy. The San Diego area was also the 1948 birthplace of the Hell's Angels, whose later habit of transporting illegally manufactured methamphetamine in the crankshaft of their bikes gave the drug its street name, crank.

Owen, a British journalist and the author of "Clubland," an account of the designer drug Special K, does a mostly deft job of juggling the myriad elements of crank's sordid history, including its impact upon our legal, chemical, cultural and even religious landscape. "No Speed Limit" has sometimes jarring shifts in chronology and mood, as Owen jaunts from the drug's late-19th century origins as a plant compound to its current vogue as a signifier for white trash, as well as its privileged spot in the early-21st century Index of Truly Bad Shit.

Owen points out that neither of these contemporary impressions of crank is unassailable. Meth has cut across class lines as both "mother's little helper" and a frighteningly powerful libido enhancer adopted by the gay club scene in the 1990s. Statistical evidence suggests it is nowhere near as prevalent as for other highly addictive substances.

In 2005 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's National Survey on Drug Use and Health (doomed to be a flawed sampling, as drug users often lie about their habits) estimated that 10.4 million Americans over the age of 12 had tried meth, with 512,000 classified as regular users. Still, that's a mere drop in the syringe when compared to 59.9 million regular tobacco users, and 121 million regular drinkers.

But whatever their costs in health and lost productivity, tobacco and alcohol are legal drugs, whereas meth is an illicit industry that now turns hundreds of millions of dollars in profit, most of it for Mexican drug cartels. Owen shows us the human face of meth abuse -- not surprisingly, an ugly one it is. A child watches her mother strip the heads off matches so she can soak them in acetone to extract phosphorous, one component in home meth manufacture. Vacant-eyed men obsessively masturbate to online porn, and toddlers sleep on the floor of their daycare center, next to a room where meth is being cooked. (Readers who want even more livid images can go to this site started by the Multnomah County Sheriff's Office in Oregon, where Deputy Bret King has assembled before-and-after mug shots of meth users in the county detention center.)

Yet the most riveting parts of "No Speed Limit" deal with the ways in which the manufacturers and distributors of the drug have consistently and disturbingly evaded efforts to stop its dissemination. This drama plays out like an illicit chemical variant of a Wile E. Coyote cartoon, with numerous characters stepping into the role of Road Runner. Chief among these is the renegade chemist Steve Preisler, who pseudonymously authored "Secrets of Methamphetamine Manufacture" and "Advanced Techniques of Clandestine Psychedelic and Amphetamine Manufacture," tomes that helped spur the rise of mom-and-pop meth labs.

Make no mistake: Even casual users can attest that meth quickly becomes a horror-show drug. But it's also one that dovetails neatly with our current national mood. Each era gets the drug it deserves -- or seems to, after the fact, when viewed through the smeary lens of pop history. Hence Coleridge and the other 18th century Romantics with their laudanum visions; Rimbaud and Verlaine sipping absinthe in 19th century Paris; the acid-tinged 1960s; coke-amped 1980s and the 1990s' sunken-eyed, vampiric heroin chic.

Methamphetamine, a drug that embodies a Platonic ideal of paranoia, perfectly suits our national mood, when sleep-deprived employees are afraid to get off the treadmill of work for fear they'll fall even deeper into debt, and sexual titillation seems both omnipresent and joyless. The erotic vampires who populated pop culture in the late 1990s and early naughts have given way to zombies stumbling or wanking or fucking their way through the detritus of the early 21st century in recent films like "28 Days Later" and "Shaun of the Dead."

Owen does a masterly job of detailing the Drug Enforcement Administration's efforts to limit or prevent the sale of so-called precursor chemicals such as pseudoephedrine, used in meth manufacture. In the mid-1980s, the DEA's Gene Haislip had succeeded in nearly eliminating Quaaludes from America's recreational drug cabinet. Haislip's attempt to make ephedrine and pseudoephedrine regulated substances was nearly derailed by the pharmaceutical industry's lobby.

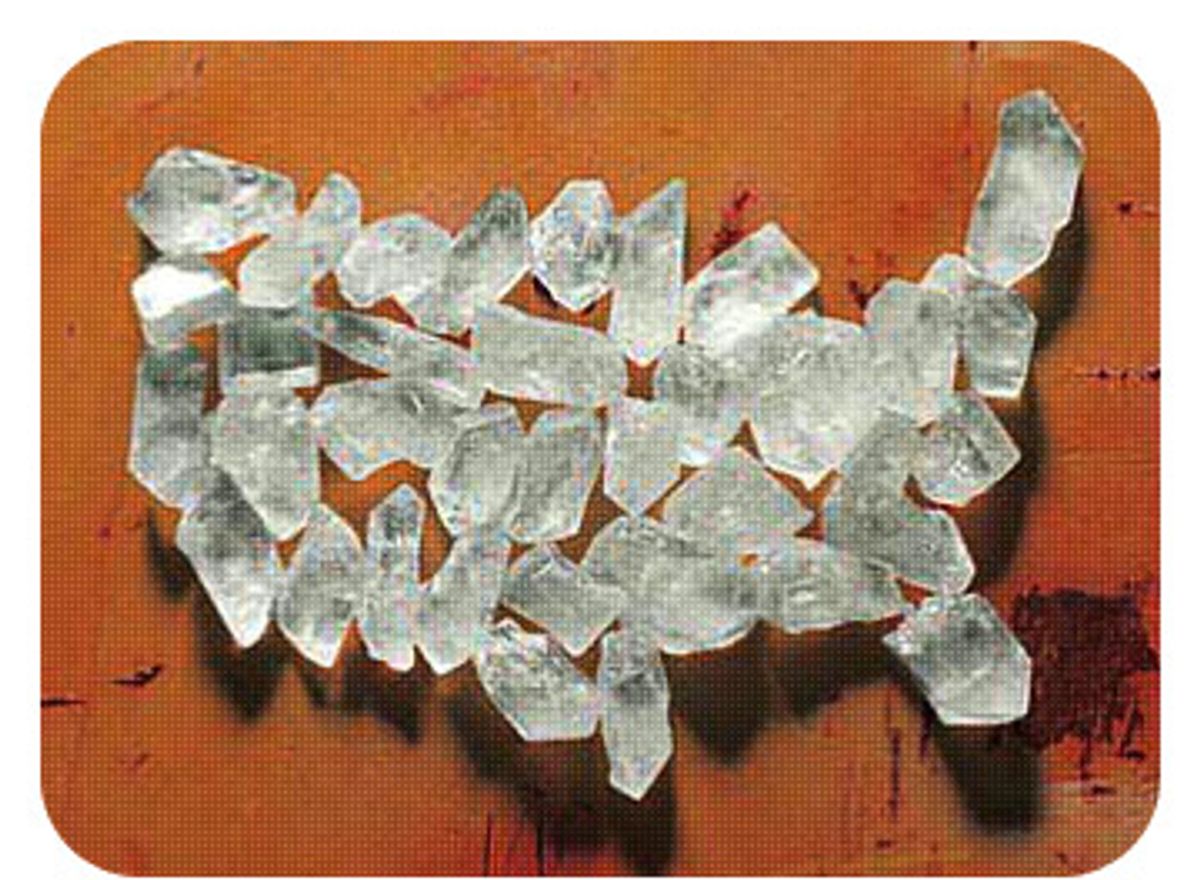

When the Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act finally went into effect in 1989, its impact was muted. Like the mythical hydra, the meth industry almost immediately sprouted new and improved means of manufacture, through the Mexican drug cartels that wrested distribution from long-established U.S. sources such as the Hell's Angels. Factories as far away as India, Pakistan, China and the Czech Republic began shipping tons of ephedrine powder to facilities south of the U.S. border. Owen writes, "'The Mexicans do it so simply, so quickly, and their network is so mobile and tight that they can make meth today and have it sold in the Midwest tomorrow,' a top official from California's Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement told the Los Angeles Times in 1995." Even more troubling, Mexican ice is rumored to be 98 percent pure, rather than the 20 percent to 80 percent found in most home-manufactured meth.

In his introduction to "No Speed Limit," Owen recounts his own experiences with the drug in the late 1980s: "For a writer, meth seemed like manna from heaven ... Writer's block? No big deal ... An impossible deadline to meet? Easy as pie. The drug banished any thought of sleep. Piles of boring research to plow through? Bring it on ... Meth, I managed to convince myself, was a valuable vocational aid, a tool of the trade like a good thesaurus or a supply of freshly sharpened pencils."

Owen's meth use was fortunately short-lived. But he has a disturbing coda toward the end of his book when he describes sampling Mexican ice. Despite his prior experience of the drug and journalist's detachment, he immediately and inexorably gets sucked into its hallucinatory maelstrom.

"Right from the first line, I could tell this was as different from the old biker meth I used to do as the biker meth was from the adulterated amphetamine sulfate of my teenage years." His experiment turns into a sleepless, five-day hallucination that involves wild sex with floating holograms and the appearance of FBI agents who accuse him of aiding terrorists. When he comes to, he muses that "the fantasy elements were so seamlessly intertwined with reality, I had spent the last four days living in a David Cronenberg movie and I couldn't tell the difference."

James Salant spent a longer time immersed in this nightmare, as detailed in "Leaving Dirty Jersey: A Crystal Meth Memoir." Salant, now 23, gives us a searing, sordid account of his 19th year, spent shooting and smoking meth and heroin in California, where the middle-class teenager from Princeton, N.J., had been sent to a rehab facility. "Leaving Dirty Jersey" recounts how its young author scored, stole, scammed and screwed his way through an increasingly desperate addiction, then managed to overcome it and write a book with the terrifying energy and harsh, overlit violence of a Tarantino movie.

Salant's prose sometimes bears the hallmarks of a tyro writer, but more often he nails the hellish tedium and despair of the addict: "I'd ... simply gotten worse at telling lies. This was inevitable, considering that believable, preferably true details are what sell a lie: a fabric of truths and easily-could-be truths woven from everyday experiences to support and hide the one thing that didn't actually happen. Which of course made telling lies nearly impossible for me, because, living on meth, I wasn't having any everyday experiences."

Salant's recovery feels excruciatingly hard won. Given the self-inflicted horrors he endured, one hopes to god he hangs onto it.

Not for the weak of heart or stomach, his memoir is a dirty bomb lobbed from the trenches of crank addiction. Owen's work, in contrast, is a report from the home front. Neither book suggests that this particular war is near over.

Shares