Film festivals are always at least semiglamorous affairs for the cities that host them, and that's certainly true in Toronto. Stars -- big ones, little ones and everything in between -- fly in from all over to attend press conferences and premieres, and their presence has the dual effect of both pleasing the public and helping to promote their current projects. But as Mark Pogachefsky, of the public relations firm mPRm, noted in an article in Friday's Globe and Mail, "Actors come in, do what they're supposed to and leave. There's not exactly a lot of time to go to Holt Renfrew." That's certainly true, and a little sad for the poor stars, as Holt Renfrew -- a glam, upscale yet old-style department store with lavish and imaginative window displays -- seems to be quite a lovely place.

But no -- there's no shopping for the stars, and certainly no hanging out in any area where they might be recognized (provided, that is, they don't want to be recognized). And so as a journalist or critic attending the festival with press credentials, the only way to see celebrities is to seek them out, either by attending a press conference or by staking out one of the premieres (and your credentials won't easily get you into the latter) for a glimpse of, say, George Clooney's left earlobe.

Tempting as it may be to chase after that elusive earlobe, it's a much better use of your time to actually see the movies. Saturday morning I had the perfect window of time to catch Joel and Ethan Coen's "No Country for Old Men," a somber, metaphorical tale about manly men in Texas (they're played by Tommy Lee Jones and Josh Brolin) and the ruthless killer, played by Javier Bardem, who haunts them both. The picture is based on a novel by Cormac McCarthy, so you know it's manly in a literary way, and it features all the trademark Coen touches, including grimly funny violence. (At one point a character daintily lifts his booted foot off the floor, lest it be stained by a spreading pool of blood.)

That's all well and good, but I do keep wondering why Bardem -- whose performance is otherwise pretty sound -- is wearing a hairdo that appears to have been inspired by the picture on the Dutch Boy paint can. It's a weird touch that smacks of affectation. And in the end, I think the movie is a lot less thoughtful, less deep, than it purports to be. Brooding doesn't necessarily equal depth.

After I left the depressed and/or laconic Texans, I flew straight to Rome, figuratively speaking, for Dario Argento's "The Mother of Tears." I don't have a taste for contemporary horror pictures -- I avoid the "Saws," the "Hostels," almost completely. I did see "House of Wax" (which I'm sure is relatively mild as these things go) and was dismayed at the protracted, sadistic quality of the violence.

Moviegoers and critics seem to be thinking, talking and writing more about movie violence these days: A.O. Scott addressed the subject in a recent Sunday New York Times piece, reflecting on the lasting influence of Arthur Penn's 1967 "Bonnie and Clyde." I don't see "Bonnie and Clyde" as a clear source of our current problem, and I hesitate to beat any drum about the prevalence of movie violence because I think the term itself is way too broad: When we talk about movie violence, do we mean the artful but brutal chase scenes and fight sequences in Paul Greengrass' "The Bourne Ultimatum"? Or the creepy killer in "House of Wax" who gives us a good three or four minutes (at least that's how long it seemed) to look forward to his lopping off a young woman's fingers with tinsnips?

It's the sadism of the latter that bothers me, and while I don't automatically read it as evidence of our "sick society," I can see it's not making our movies any better, either. And that's why I loved "The Mother of Tears." I haven't seen any recent Argento -- I've been warned that his newer movies don't have the nutball stylishness of earlier pictures like "The Bird With the Crystal Plumage" or "Four Flies on Gray Velvet" or, my favorite, "Suspiria."

But "The Mother of Tears" is so unapologetically loopy and lush and ridiculous that I found it irresistible. Now look, I'm not going to tell you that there isn't some sick stuff in this thing: When a trio of crazed demons began strangling a woman with her own entrails -- and this is within the first 10 minutes -- I began to think that a peaceful afternoon spent searching for that Clooney earlobe didn't sound like such a bad thing. But I sure as hell wasn't leaving that theater. In "The Mother of Tears" Argento revisits lots of favorite motifs, to use a noun that's perhaps more delicate than is warranted: There are the usual instances of knives being plunged into women's chests (I think I read somewhere that that's a kind of phallic symbolism. Y'think?), as well as an occurrence of what a friend and colleague calls "the old pike up the vag," a chestnut Argento has used so many times it's almost endearing.

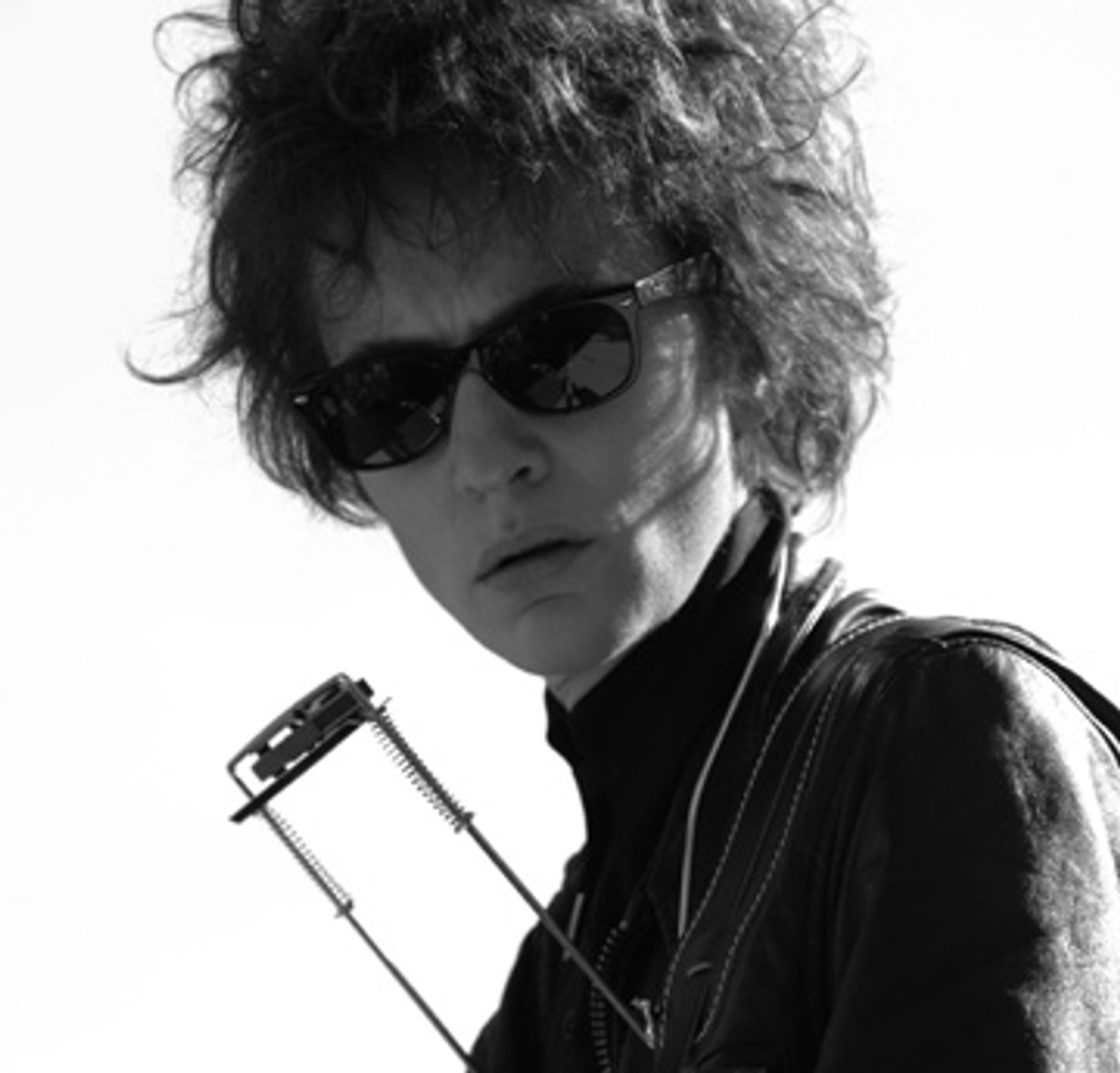

I don't particularly like watching that stuff; I confess to being a proponent of the watch-through-the-fingers thing. But Argento's sick violence is of the old-school kind. It's swift and uncluttered; he gives you five seconds to anticipate it, another five to get it over with, and then he's on to the next thing. That next thing might involve an ingenious eyeball-stabbing device (and this is where I highly recommend the tried-and-true watch-through-the-fingers technique), but again -- 10 or 15 seconds, and it's over.

And then you're left to simply enjoy the squirrelly riches that Argento tucks so lovingly around the blood and gore, which is very obviously and exuberantly fake, anyway. In "The Mother of Tears" two Rome museum curators -- one of them, the heroine of this tale, is played by the wonderfully brash and sensuous actress Asia Argento, Dario's daughter -- receive a curious stone urn and can't resist opening it. Inside are three fat stone statues with ugly faces, a primitive jeweled dagger and a scrap of cloth that we learn is a ceremonial dress from pagan times. The thing looks like -- no, wait, I'm telling you, it is -- a cut-off sweatshirt decorated with mysterious runes written in glitter glue. It also happens to be a minidress: When the powerful witch Mater Lachrymarum slips it on, it barely covers her bum -- and what a bum it is!

But I'm getting ahead of myself. In "The Mother of Tears," the opening of that urn restores the powers of the beautiful and deadly Third Mother, one of three witches responsible for spreading pain, tears and darkness throughout the land. Now that Mama Lach is back in action, witches from around the world are headed to Rome for her big house party-slash-orgy -- dressed in black miniskirts and Patrick Nagel-style eye makeup, they descend upon the city like Beelzebub's "Girls Gone Wild." Violence erupts in the streets: Crazed, possessed maidens run around topless; priests who know a little bit too much about the occult face gruesome ends. "The Mother of Tears" is wild and untamed, a celebratory feat of gonzo artistry. Argento clearly didn't have a lot of money to spend on the picture, but it still has a sort of cheapie-luxe look: The women's clothes, for example, aren't expensive, but they nonetheless give you a pretty clear sense of what a Satan doll's idea of glamour would be.

"The Mother of Tears" is as sick as hell. But at least it's got class.

Shares