Bless the Associated Press for unearthing, through careful and diligent investigation, Comcast's shameful, hidden Internet traffic-management scheme.

Comcast, the AP determined, actively manages data on its network by using software to essentially masquerade as its subscribers' machines. When non-Comcast Internet subscribers request files from your Comcast-connected machine -- as happens in peer-to-peer file-sharing applications -- Comcast's technology steps in and tells the non-Comcast subscriber you're not available.

This is a difficult story to explain, but it's quite important. For years, consumer advocates have been demanding that Congress and/or the Federal Communications Commission impose "network neutrality" regulations that would force broadband providers (like Comcast) to treat all data on a network equally. Lawmakers have so far failed to do so.

Broadband providers, meanwhile, insist that they do treat all traffic equally, but they reserve the right to use certain technologies to "manage" data on their network. The Comcast plan suggests that broadband providers mean something very broad by "traffic management" -- including, it appears, purposefully stepping into your network sessions to shut them down.

To understand why this whole process is so egregious, let's look at it in FAQ format.

What is Comcast doing, and why?

The Internet is awash in peer-to-peer applications. In such programs, you get (and send) pieces of a file from (and to) computers all over, rather than communicating with a single big server (as you do, say, when you download a YouTube video).

The technology first gained prominence with music- and movie-sharing apps -- Napster, Kazaa, etc. -- but today P2P tech is deployed in all kinds of software, including for Internet phone services (Skype) and TV (Joost). BitTorrent, one of the most popular peer-to-peer protocols, is used to download all kinds of stuff, both legal and illegal.

Broadband providers have a love-hate relationship with peer-to-peer apps. On the one hand, peer-to-peer programs increase the demand for high-speed access -- many people decide to subscribe to broadband service only because of amazing apps like Kazaa, BitTorrent, Skype and others.

But peer-to-peer programs also eat up space on a network, because every user is downloading and uploading data for long periods of time. And for providers, a clogged network costs money and hurts their reputation. (If peer-to-peer users use up all the space, other users complain that their Web surfing is too slow.)

Providers thus have an incentive to reduce peer-to-peer traffic on their networks. But they can't do so openly because, remember, a lot of people only pay for services like Comcast in order to use peer-to-peer programs.

Moreover, in their marketing copy, Comcast and other broadband companies play up the "unlimited" nature of their plans. They don't really want to tell people that, actually, they're managing their networks so that you can't do all you want with it (though in the fine print that subscribers never read, they all reserve the right to do so).

The upshot, then: Comcast wants to manage its traffic. It just doesn't want people to know that it does.

So how does Comcast silently manage traffic?

The effort that the AP reports on was first discovered by Robb Topolski, a software engineer who hangs out at the forums on DSLReports.com. In May, he posted a detailed note on the forum describing Comcast's traffic management operation.

The system works, Topolski guessed, by limiting communication at the "boundary" of Comcast's network -- that is, the point where Comcast's network connects with the larger Internet.

To detect peer-to-peer communication, Comcast inspects packets -- the smallest meaningful bit of information on the Internet -- as they cross the network boundary. If Comcast determines that there are too many peer-to-peer users within its network sending files to people outside the network, it begins to interrupt the connections between Comcast users and those beyond Comcast.

To interrupt these communications, Comcast appears to be using technology made by a network management company called Sandvine. What's remarkable is how Sandvine manages to disrupt peer-to-peer traffic.

As Topolski describes it, Sandvine's system sends a "forged" packet to each of the two computers engaged in a peer-to-peer transfer -- the forged packet looks like it came from the other person's computer, and it basically tells each machine that the other is unavailable, ending the transfer.

The AP describes this marvelously: "Each PC gets a message invisible to the user that looks like it comes from the other computer, telling it to stop communicating. But neither message originated from the other computer -- it comes from Comcast. If it were a telephone conversation, it would be like the operator breaking into the conversation, telling each talker in the voice of the other: 'Sorry, I have to hang up. Goodbye.'"

So what? Isn't Comcast only stopping illegal file sharing?

No! Comcast's system doesn't look at the copyright status of the materials you're trading -- it only looks at the technical protocols you're using to conduct the trade, and blocks access based on those protocols alone. And just because people use these technical protocols to trade illegal materials doesn't mean that every use is illegal.

Case in point: To test how Comcast is managing traffic, AP reporters tried to download a version of the King James Bible using BitTorrent. The Bible, of course, is perfectly legal to trade; indeed, some people might say that putting the good book up for others to download is a blessed thing.

But when AP reporters tried to download the Bible from Comcast subscribers in Philadelphia and San Francisco, they found that the connections were either blocked outright or delayed. (Downloads from other providers worked fine.)

In his post, Rob Topolski points to another way Comcast's system can disrupt legitimate traffic.

Say you have a band and you want to put up your CD on a file-sharing network for others to download. If you're a Comcast subscriber, you would find this very hard to do -- since Comcast limits peer-to-peer connections at the network boundary, "the time it would take to get a complete copy of a music file to a point outside of the Comcast network is dramatically increased," Topolski wrote.

OK, but so what? Even if Comcast is blocking peer-to-peer traffic, that doesn't affect me -- all I'm doing is browsing the Web!

Sure, this only affects peer-to-peer transfers -- at least, as far as we know. The most alarming thing about this scheme is that Comcast is conducting it on the sly. It didn't alert anyone to its filtering mechanism -- not its customers, not other ISPs, nobody.

Indeed, Comcast is still not coming clean. A company rep tells the AP: "We rarely disclose our vendors or our processes for operating our network for competitive reasons and to protect against network abuse," he said.

And then there's the sheer dishonesty of the practice. Comcast's system is silently listening in to your Internet traffic and inserting itself into the communication in order to shut it down.

If the company feels justified doing this on peer-to-peer connections, what's to say it wouldn't feel similarly justified shutting down or slowing down your communication with Amazon.com, or NYTimes.com, or YouTube or any other online service (whether because it doesn't like the content, or because it's got an economic incentive, or because it's just mean) -- and all without telling us?

OK, so what can we do about this?

It'd be wonderful if the solution was to simply stop subscribing to Comcast. If that would make you feel better, by all means, cancel your subscription.

But know this: Other broadband vendors have not distinguished themselves on the issue of network neutrality. In general, major broadband companies say they should be free to manage traffic on their networks, and it's impossible to tell how expansively they understand that "management" role.

If Comcast is saving money by adopting such methods, you can bet others are already doing so, or soon will. It would be shocking if Comcast were the only one.

But there is an obvious solution. It has been obvious for some time. We need a law!

Providers should be proscribed from interrupting customers' connections or, at the very least, from doing so secretly -- if they're going to disrupt your traffic in any way, they should be forced to tell you how.

Broadband companies have long argued that network neutrality regulations are unnecessary. The Comcast scheme pretty definitively proves otherwise.

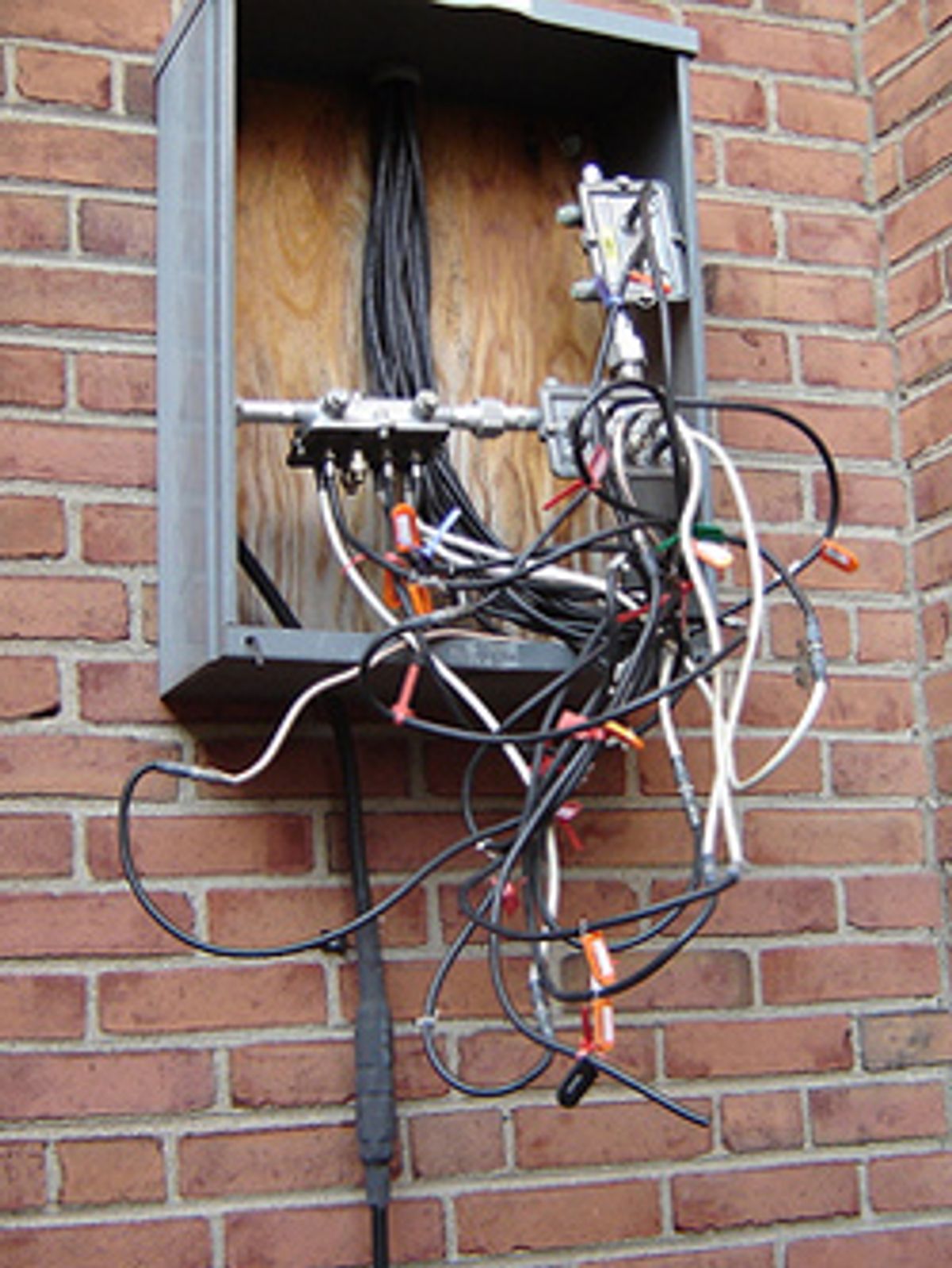

[Flickr picture by dmuth.]

Shares