In early 1967, word hit the U.S. about a new British group: a killer trio called Cream. The Beatles, the Stones and the Who were the reigning champs of rock at the time, but they didn't sell themselves as virtuosos the way Cream did. These guys were all about chops.

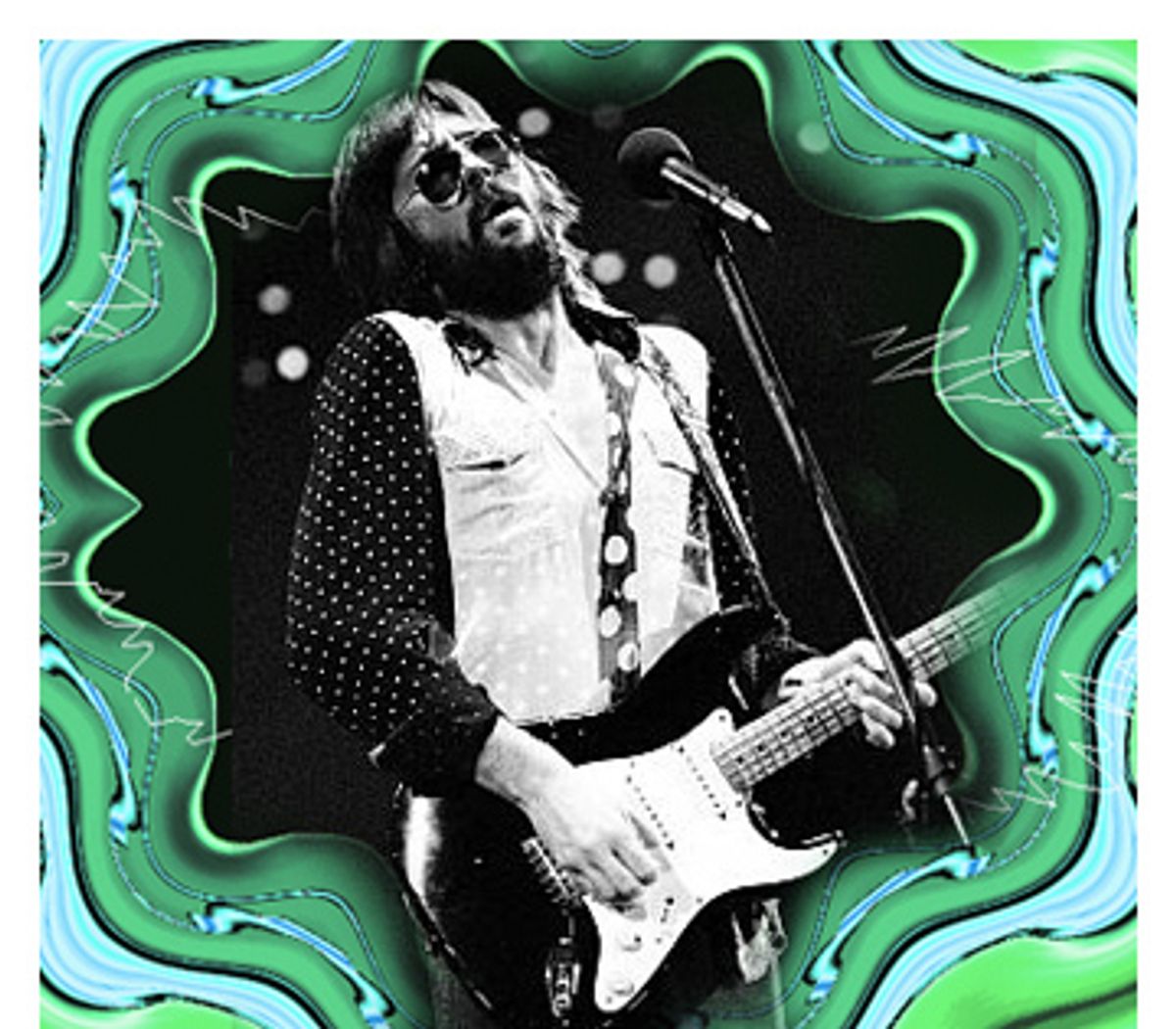

"I Feel Free," the first song on Cream's first album, announced that something new had arrived in pop music -- something hard, cold and scarily precise. Ginger Baker's mathematical, machine-gun-like drumming and Jack Bruce's sophisticated bass line set the stage, and then in wailed this spine-shivering guitar solo by Eric Clapton, the notes bent uncannily up to pitch and so overloaded with sustain they seemed to ooze liquid electricity. Clapton floated along through the solo like a malevolent hummingbird, and then at the end flipped the switch on his Gibson into the treble position and just blasted off a short, savagely accurate blues riff to take it home. You could hear Albert King and Buddy Guy and the whole history of electric blues guitar in that teeth-gritting riff, but it was fed through a monstrous Marshall amp and transformed into something predatory and exultantly modern. It was one of the first guitar solos in rock history that had a spotlight on it.

That spotlight had been shining on Eric Clapton since his days with the Yardbirds, the groundbreaking British blues-rock group, and then with John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. In 1965, delirious fans started scrawling "Clapton is God" graffiti on London walls. And for about five more years, Clapton was god -- or at least the second-best guitarist in rock. (Like the great Joe Frazier, who had the misfortune to fight at the same time as Muhammad Ali, Clapton had the bad luck to hit his peak just when a guy named Jimi Hendrix appeared on the scene.) His solos were at once architectural and fiery, heavily indebted to American blues players but unmistakably Clapton.

Clapton made four great albums with Cream and another excellent one with the heavily hyped supergroup Blind Faith, released a decent solo album, and a pretty good double album, "Layla," in 1970. But musically, that was his high-water mark. Since those days, Clapton has released dozens of albums and had lots of big hits, but he did by far his best work between the ages of 21 and 25.

This isn't unusual in rock, where age does not always bring majesty. But for fans whose interest in rockers' lives is pretty much confined to carved-in-Mount-Rushmore figures like the Beatles and Bob Dylan, the new Clapton autobiography thus starts out at a considerable disadvantage, one that can uncharitably be summed up as, "Who cares?" Clapton did gain personal notoriety for his tormented relationship with George Harrison's wife Pattie, for beating alcoholism and drug addiction, and for the tragic death of his young son. But is the life story of a former rock legend turned artistic B-lister really worth reading?

The answer turns out to be yes. "Clapton" is really two stories in one, and he tells them both pretty well. On the one hand, it's a classic rocker's autobiography, a big bag of buttered celebrity popcorn, filled with inside dish about famous musicians, drunken, stoned escapades and abortive relationships. But it's also a redemption narrative, in which a wastrel is saved by grace after hitting bottom.

This may not sound like a promising combination. Rock autobiographies can be superficial, gossipy and dumb. And redemption narratives are frequently marred by psychobabble and after-the-fact moralizing. Fortunately, though Clapton's perspective is that of a survivor, he neither flagellates himself nor tries too hard to justify his screw-ups. Mostly, he simply presents his misadventures with a kind of no-nonsense wryness. It's true that he does posit some self-help-tinged explanations for why he kept screwing up, which sometimes verge on the canned. But even canned self-analysis can contain truth. In the end, Clapton ended up cleaning up his own mess, and you'd have to be cynical indeed not to be moved by his tale of redemption.

In Clapton's account, many of his later problems with emotional intimacy are traceable to a dark family secret. Clapton's real mother, Pat, gave birth to him out of wedlock and handed him over to her parents, Rose and Jack, who raised him as if he was their child. When he discovered the truth at an early age, he withdrew into himself. Later, when the truth had been acknowledged by all, he blurted out to Pat in front of his grandparents, "Can I call you Mummy now?" His mother replied, "I think it's best, after all they've done for you, that you go on calling your grandparents mum and dad." Clapton writes, "in that moment I felt total rejection." He attributes his decades-long inability to form lasting relationships with women to this early sense of inadequacy.

Clapton grew up in the village of Ripley, in rural Surrey, where life horizons were limited. He began to play the guitar while at art school. That's also where he first heard the blues. It was another example of the collision of black American music with British youth, the strange alchemy that produced so much of the greatest pop music of the 20th century. "It's very difficult to explain the effect the first blues record I heard had on me, except to say that I recognized it immediately," he writes. "It was as if I were being reintroduced to something that I already knew, maybe from another, earlier, life."

He set about trying to play like Big Bill Broonzy and Jimmy Reed, and later was introduced to John Lee Hooker, Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters and Little Walter. But the revelation was Robert Johnson, the brilliant, mysterious Delta blues singer and guitarist who was to serve as the lodestar for Clapton's entire career. "At first the music almost repelled me, it was so intense, and this man made no attempt to sugarcoat what he was trying to say, or play ... After a few listenings I realized that, on some level, I had found the master, and that following this man's example would be my life's work."

After starting out with a local band called the Roosters, Clapton rapidly moved up through the Yardbirds, the Bluesbreakers and finally Cream, which quickly became an enormous success. Clapton was especially proud of the group's second album, "Disraeli Gears," but was hurt when British fans, gaga over Jimi Hendrix, slighted the album. As Cream played endless, grueling American tours, Clapton became further disenchanted. "[P]laying to audiences who were only too happy to worship us, complacency set in. I began to be quite ashamed of being in Cream, because I thought it was a con. It wasn't really developing from where we were." What crystallized his dissatisfaction was hearing "> the classic first album by the Band. "Here was a band that was really doing it right, incorporating influences from country music, blues, jazz, and rock, and writing great songs. I couldn't help but compare them to us ... I wanted out."

His desire to take his music in new directions and escape what he calls the cult of "pseudo-virtuosity" was laudable. But as his solid but unspectacular subsequent career showed, good intentions and good taste don't always translate into great music. "Clapton" doesn't really explore why, and probably couldn't. (One of the book's shortcomings is that it rarely discusses music in any depth.)

Clapton wanted to shed his superstar image and just labor humbly in the rock vineyards. He writes that he was drawn to what his friend Steve Winwood called "unskilled labor, where you just played with your friends and fit the music around that." By his own account Clapton has been happier, and had more fun, playing with solid, mostly American musicians, singing, performing conventional rock songs with hooks, and eschewing nine-minute solos, than he did when he was a guitar deity. That's nice, but the music is also just ... nice.

Luckily for the reader, Clapton's personal life is a little more intriguing -- and a little less nice. After quitting Cream and the subsequent group Blind Faith, Clapton retreated to his country estate, Hurtwood, and began hanging out with George Harrison, who lived nearby, and sinking into the addictive quicksand of a long-running relationship with Harrison's wife, Pattie, who inspired Clapton's song "Layla."

"I think initially I was motivated by a mixture of lust and envy, but it all changed once I got to know her," Clapton writes. "I had never met a woman so complete, and I was overwhelmed. I realized that I would have to stop seeing her and George, or give in to my emotions and tell her how I felt."

Eventually, Clapton did tell Pattie how he felt, but not until after he had gone to bed with her sister in what he describes, without irony, as an attempt "to get closer to her." In the rock 'n' roll world in 1969, irony about such romantic tactics might have been pointless, as the following anecdote, which Clapton describes with world-class understatement as "curious," shows. Clapton writes that George, "who was motivated just as much by the flesh as he was by the spirit," suggested that "I should spend the night with Pattie so that he could sleep with Paula. The suggestion didn't shock me, because the prevailing morality of the time was that you just went for whatever you could get, but at the last moment he lost his nerve." Clapton ended up sleeping with Paula.

Having nonchalantly reminded readers that his seduction of his friend's wife might not be such a monstrous betrayal as it appeared, Clapton goes on to describe how he finally got up the nerve to tell Pattie that she was the one he really wanted, not her sister. They "ended up kissing, and I sensed for the first time that there was some kind of hope for me. I knew then what I had suspected for some time, that all was not well in her marriage." Buoyed by this development, Clapton flipped his Ferrari over on the way home. After climbing out of the upside-down car, he realized he didn't have a driver's license and started running, planning to make up a story that someone had stolen his car. With the luck of a rock star, he got away with it and the police never got involved.

Soon thereafter Clapton played a gig with the famous New Orleans musician Dr. John. After he poured out his romantic woes, "The Night Tripper" mixed him up a love potion, complete with instructions, which Clapton faithfully followed. Sure enough, he shortly ran into Pattie, "and we just kind of collided, to the point where there was no turning back." Clapton saw George a while later at a party, and blurted out, "I'm in love with your wife." Clapton writes, "The ensuing conversation bordered on the absurd. Although I think he was deeply hurt -- I could see it in his eyes -- he preferred to make light of it, almost turning it all into a Monty Python situation."

Much of the appeal, and weirdness, of "Clapton" comes through in this anecdote. For most writers, this would be a climactic incident. But Clapton's life is so exhaustingly filled with stuff -- acid trips with the Beatles, suicidal romantic adventures, playing music with legends, adulation, money, fame, world travel, hot and cold running sex -- that there's just no time. Besides, it wouldn't be true to his life for him to ponder anything too deeply, because he apparently never did at the time.

Clapton's capacity for self-insight diminished to zero during what he calls "the lost years." He had begun using heroin and cocaine, which contributed to the demise of the Dominos. "This was the beginning of a period of serious decline in my life," Clapton writes. One trigger was the death of Jimi Hendrix, who had become a good friend. Others were the illness of his grandfather, and his unrequited love for Pattie, who still refused to leave Harrison. For several years he holed up at Hurtwood with his girlfriend, seeing almost no one.

Prodded by Pete Townshend of the Who, Clapton finally underwent an eccentric course of treatment that involved electric acupuncture. But he kicked heroin only to take up alcohol. Clapton went to work on a farm as part of his rehab, and after a day of physical labor he and a pal would hit the pubs and drink until they could barely stand up. Soon he was a full-fledged alcoholic.

Meanwhile, he had heard from mutual friends that George and Pattie weren't getting along. Clapton's wit flashes in his description of the marital scene: "[T]hey were living in virtual open warfare at Friar Park, with him flying the 'Om' flag at one end of the house and her flying a Jolly Roger at the other." Clapton was finally able to convince Pattie to leave George, but having got what he wanted, Clapton didn't know what to do with it. Clapton writes, "Rather than being a mature, grounded relationship, it was built on drunken forays into the unknown ... my addiction was always in the way."

Clapton was prone to outrageous behavior when drunk, which was now most of the time. He did one entire show lying down onstage. He was particularly fond of crude practical jokes. The nadir came when he decided to play a trick on his drummer, who had taken a girl back to his hotel room in Honolulu. Intending to spoil his pal's night and give him a good scare, Clapton grabbed a samurai sword, walked out onto a ledge 30 stories up, and made his way into the drummer's bedroom. Neither the drummer nor the girl were amused, and neither were the police, who came to the door with guns drawn, thinking he was some kind of assassin.

Clapton was also sleeping with every girl who was available on the road, a practice abetted by his transparently self-serving rule that women (meaning significant others) were not allowed on tour. Pattie finally caught Clapton with a girl at Hurtwood, and left him. But Clapton won her back by proposing to her, after his manager forced his hand by leaking a story to a British tabloid saying that they were planning to wed.

His drinking was now out of control, and almost killed him: An ill-advised attempt to go cold turkey for the weekend led to his having a grand mal seizure. But even that didn't stop him. What did, tellingly, was a fishing mishap. "I'm a country boy, and I've always thought of myself as a reasonably good fisherman," Clapton writes. When some professional fisherman witnessed him fall drunkenly onto a brand-new reel, breaking it in two, "That was it for me. The last vestige of my self-esteem had been ripped away. In my mind being a good fisherman was the last place where I still had some self-esteem." Shortly afterward he checked into Hazelden, the world-renowned clinic for alcoholics in Minnesota. It was 1982 and he was 36 years old.

Clapton cleaned up, but soon relapsed. When he became the father of a son, Conor, every second of the time he was playing with him he thought about having a drink. In 1987, driven by fear that Conor would grow up to see him as the drunken mess that he was, he returned to Hazelden, where he had a dramatic revelation that proved to be what he says was the turning point in his life: "In the privacy of my room I begged for help. I had no idea who I thought I was talking to, I just knew that I had come to the end of my tether, that I had nothing left to fight with ... I surrendered." Clapton writes that he has never wanted to take a drink or a drug in the 20 years since that moment.

On March 20, 1991, Clapton's son, Conor, playing in his mother's apartment in New York, ran through an open window and fell 49 stories to his death. Clapton's account of this awful event is characteristically muted. As throughout the book, his low-key tone comes across as honest rather than superficial. At the funeral, he writes, he was "quite detached, in a permanent daze." In the months that followed, what was important was to "keep moving; under no circumstances stay still and feel the feelings. That would have been unbearable ... When I try to take myself back to that time, to recall the terrible numbness that I lived in, I recoil in fear." It was music that finally let him face what had happened: He writes that he wrote the song "Tears in Heaven" "to stop from going mad."

The other thing that saved Clapton was his membership in a 12-step program, and his realization that he could help others. "I was suddenly aware that maybe I had found a way to turn this dreadful tragedy into something positive," Clapton writes. "I really was in the position to say, 'Well, if I can go through this and stay sober, then anyone can.' At that moment I realized there was no better way of honoring the memory of my son." In part by donating his entire collection of guitars, Clapton has since raised millions of dollars for Crossroads, the alcohol and drug recovery center he founded.

So who is Eric Clapton? The pre-recovery Clapton is a cipher, a cloud, whose picaresque adventures mask the fact that he was often a passive bystander at his own life. The later Clapton has a definite shape: He's found his truth, although he wouldn't use that big a word. This before-and-after quality could feel sentimental and clichéd, like many 12-step narratives. But it doesn't, and the reason is that Clapton doesn't take himself that seriously -- and he doesn't reject the man he once was. Clapton No. 1 had a life, even though much of it just kind of happened to him. He had a lot of fun, despite being ripped to the gills half the time. Clapton No. 2 knows that, and even seems to appreciate it. In a culture saturated with I-was-lost-but-now-I'm found tales, what makes "Clapton" worthwhile is that it celebrates being found, but doesn't try to deny the pleasures and pains of being lost.

Shares