Every aspect of Bush's foreign policy has now collapsed. Every dream of neoconservatism has become a nightmare. Every doctrine has turned to dust. The influence of the United States has reached a nadir, its lowest point since before World War II, when the country was encased in isolationism.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose soul President Bush famously claimed to peer through, is scuttling arms control agreements and cutting his own deals with the Iranians. The Turkish army is poised to invade northern Iraq in pursuit of Kurdish militants that the Iraqi government and the U.S. allowed to roam freely. The resurgent Taliban, given a second life when Bush drained resources from Afghanistan for the invasion of Iraq, is besieging the countryside, straining the future of the Western alliance in the form of NATO. Pakistan, whose intelligence service and military contain elements that sponsor the Taliban and al-Qaida, remains an epicenter of terrorism. Gen. Pervez Musharraf's imposition of martial law in Pakistan on Nov. 3 was his second coup, reinforcing his 1999 military takeover. Facing elections in January 2008 that seemed likely to repudiate him and an independent judiciary that refused to grant him extraordinary powers, he suspended constitutional rule. Toothless U.S. admonitions were easily ignored.

Gone are the days when the stern words of a senior U.S. official prevented rash action by an errant foreign leader and when the power of the U.S. served as a restraining force and promoted peaceful resolution of conflict. In the vacuum of the Bush catastrophe, nation-states pursue what they perceive to be their own interests as global conflicts proliferate. The backlash of preemptive war in Iraq gathers momentum in undermining U.S. power and prestige. The resignation last week of Bush's close advisor, Karen Hughes, as undersecretary of state for public diplomacy, whose mission was to restore the U.S. image in the world, signaled not only failure but also exhaustion. The administration's ventriloquism act of casting words into the mouth of the president's nominee for attorney general, former federal Judge Michael Mukasey, who would not declare waterboarding torture, demonstrated that Bush is less concerned with the crumbling of America's reputation and moral authority than with preventing an attorney general from prosecuting members of his administration, including possibly him, for war crimes under U.S. law.

The neoconservative project is crashing. The "unipolar moment," the post-Cold War unilateralist utopia imagined by neocon pundit Charles Krauthammer; "hegemony," the ultimate goal projected by the September 2000 manifesto of the Project for the New American Century; an "empire" over lands that "today cry out for the sort of enlightened foreign administration once provided by self-confident Englishmen in jodhpurs and pith helmets," fantasized by neocon Max Boot in the Weekly Standard a month after Sept. 11, have instead produced unintended consequences of chaos and decline. Dick Cheney's and Donald Rumsfeld's presumption that successful war would instill fear leading to absolute obedience and the suppression of potential rivalries and serious threats -- the "dangerous nation" thesis of neocon theorist Robert Kagan -- has proved to be the greatest foreign policy miscalculation in U.S. history.

The quest for absolute power has not forged an "empire" but provoked ever-widening chaos. The neocons have been present at the creation, all right. But this "creation" is not another American century, in emulation of the post-World War II order fashioned by the so-called wise men, such as Secretary of State Dean Acheson, a consummate realist, who Condoleezza Rice continues to insist is her model. Squandering the immense influence of the U.S. in such a short period has required monumental effort. Now the fog of war clears. On the ruin of the neocons' new world order emerges the old world disorder on steroids.

Musharraf's coup spectacularly illustrates the Bush effect. His speech of Nov. 3, explaining his seizure of power, is among the most significant and revealing documents of this new era in its cynical exploitation of the American example. In his speech, Musharraf mocks and echoes Bush's rhetoric. Tyranny, not freedom, is on the march. Musharraf appropriates the phrase "judicial activism," the epithet hurled by American conservatives at liberal decisions of the courts since the Warren Court issued Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed segregation in schools, and makes it his own. This term -- "judicial activism" -- has no other source. It is certainly not a phrase that originated in Pakistan. "The judiciary has interfered: That's the basic issue," Musharraf said.

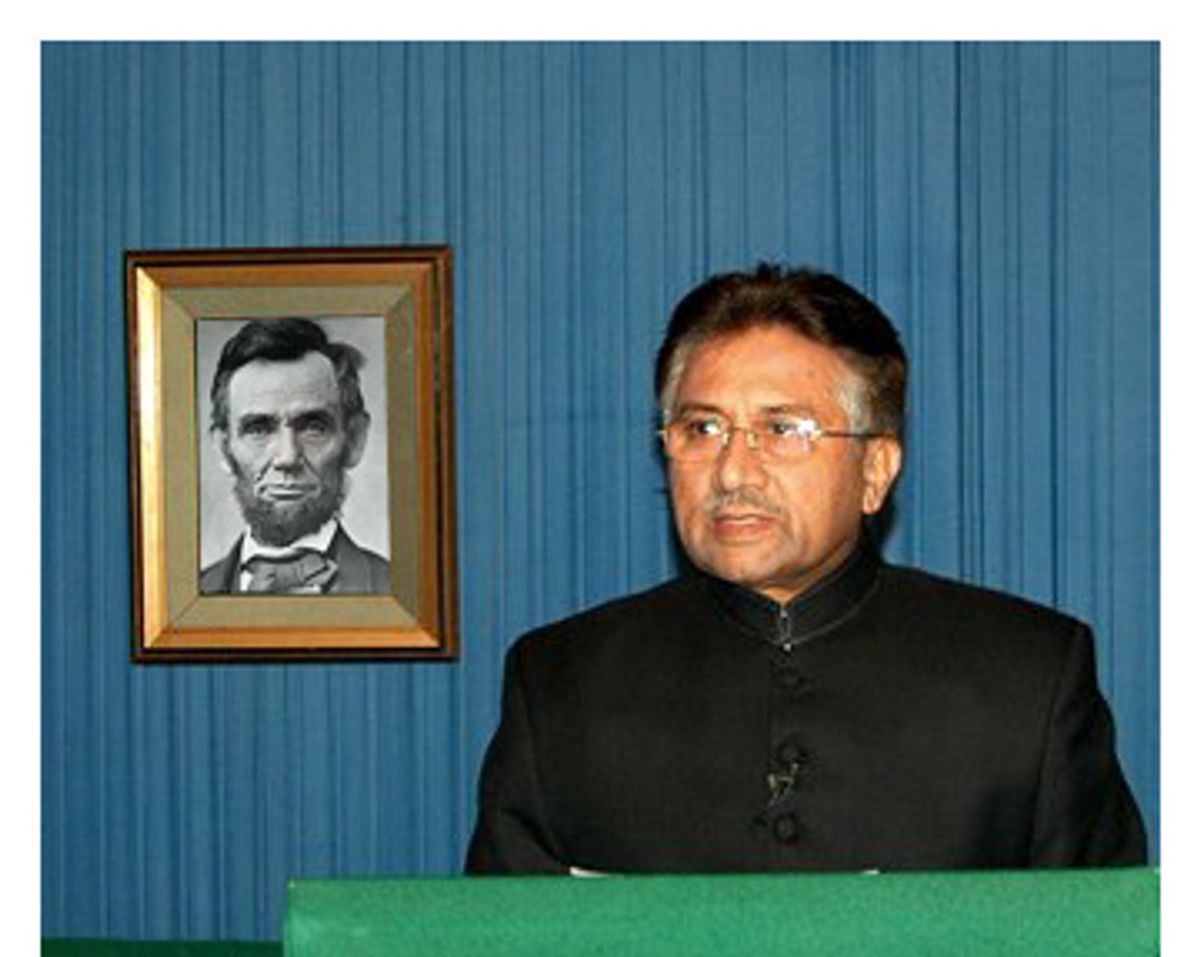

Indeed, under Bush, the administration has equated international law, the system of justice, and lawyers with terrorism. In the March 2005 National Defense Strategy, this conflation of enemies became official doctrine: "Our strength as a nation state will continue to be challenged by those who employ a strategy of the weak using international fora, judicial processes, and terrorism." Neoconservative lawyers, in and out of the administration, have strenuously argued that the efforts to restore the Geneva Conventions, place detainees within the judicial process and provide them with legal representation amount to what they denigrate as "lawfare" -- a sneering reference to "welfare" and the idea that detainees are akin to the unworthy poor. Lawyers for detainees, meanwhile, are routinely insulted as "habeas lawyers," as though they were agents of terrorists and that arguing for the restoration of habeas corpus proves complicity "objectively" with terrorists. Rather than cite these neoconservative talking points directly or invoke the authority of Bush, whose feeble protestations he brushed aside, Musharraf slyly quoted Abraham Lincoln, who suspended habeas corpus in Maryland and southern Indiana during the Civil War. (The U.S. Circuit Court of Maryland overturned his act. In 1866, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Milligan that civilians could not be tried before military tribunals when civil courts were functioning.) In Musharraf's version, Lincoln is his model, taking executive action in order to save the nation: "He broke laws, he violated the Constitution, he usurped arbitrary powers, he trampled individual liberties, his justification was necessity." Musharraf, of course, as he suspends an election, leaves out the rest of Lincoln, not least the difficult election of 1864, which took place in the middle of the Civil War.

But where did Musharraf get his warped idea of Lincoln as dictator and America as an example of tyranny? Not quite from diligent study of American history. According to a 2002 interview with Ikram Sehgal, managing editor of the Defense Journal of Pakistan, Musharraf received this notion from his reading of Richard Nixon's book "Leaders," published in 1994, in which Nixon discusses Lincoln's measures taken under extreme duress with ill-disguised admiration. Thus, for Musharraf, as for Cheney and Bush, Nixon's vision of an imperial president lies at the root of their actions in creating an executive unbound by checks and balances, unaccountable to "judicial activism." Since declaring a state of emergency, Musharraf has rounded up thousands of lawyers and shut down the courts, while halting offensive military action against terrorists. In the name of combating terrorism, even as parts of his government are in league with them, he launches an attack on those who profess democracy.

The Bush administration finds itself devoid of options. Neoconservatives are left, happily at least for some of them, to defend torture. They have no explanations for the implosion of Bush's policies or suggestions for remedy. Self-examination is too painful and in any case unfamiliar. Bush regrets Musharraf's martial law, yet tacitly accepts that the U.S. has no alternative but to support him in the war on terror that he is not fighting -- and is using for his own political purposes. On the rubble of neoconservatism, the Bush administration has adopted "realism" by default, though not even as a gloss on its emptiness. Bush still clings to his high-flown rhetoric as if he's warming up for his second inaugural address. But this is not rock-bottom; there is further to fall.

Shares