To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

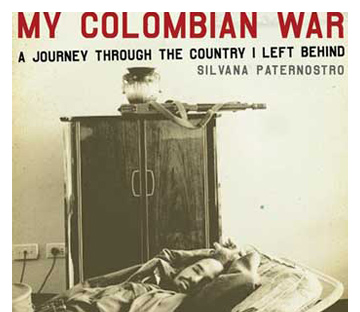

A kidnapping target in her native Colombia, journalist Silvana Paternostro returned there to document life beyond the drug war. In 1999, 22 years after she left to come to the United States, Paternostro decided to “open up the Pandora’s box” of her past. What followed was a series of trips that became the material of “My Colombian War,” a book she calls “a mix of memoir and reportage about Colombia and all its complexities.”

As a reporter for publications such as the New Republic, the Paris Review and Newsweek, Paternostro knows that Americans rarely stop to think about the legacy of the war that disappeared from view after 9/11: the drug war. Like the billions of dollars in military and humanitarian aid the U.S. has spent in Colombia, Paternostro’s book provides no happy endings. It’s not giving away too much to quote her conclusion that, for Colombia and for her, things “did not work out between us.”

Not for lack of trying. In September of 2001, Paternostro returned to her family farm, El Carmen, in the north, for a New York Times Magazine story. As the daughter of wealthy landowners and thus, Colombian logic goes, a target for kidnapping, she required heavily armed escort for her trip that lasted only four hours. “My Colombian War” explores the “feudal dynamics” that result in such brutal reality. Paternostro’s earlier book, “In the Land of God and Man” (1999), established her reputation for turning a critical eye to her own culture, as a woman who dared to take on the sacred cows of Latin American Catholicism, machismo and patrician values, from within.

NNow, as a self-described outsider and yet still a member of the Colombian elite (Paternostro’s mother descends from French aristocracy who fought on the Conservative government side of the same war Gabriel García Márquez depicts in “One Hundred Years of Solitude”), Paternostro’s tangled relationships with the places and people of her Colombian past provide an apt metaphor for the sticky complexities of the country itself, and American involvement there. Colombia remains exceedingly violent — the UNHCR counts 2 million to 3 million internally displaced persons, second only to Sudan — and “My Colombian War” comes out this month in the U.S. with names changed to protect “the privacy and safety of the Colombians still living amid violent conflict.”

Paternostro spoke with Salon in New York (with an interruption to field a phone call from Aleida March, Che Guevara’s widow) about Colombia, her involvement in Steven Soderbergh‘s pair of Che biopics, and the literary genre she calls “nonfiction magical realism.”

In a recent speech to the Council on Foreign Relations, Condoleezza Rice declared that “Colombia is on a trajectory of positive change — politically, economically and socially,” marveling that “Colombia’s transformation in less than a decade from failing state to thriving democracy is one of the greatest victories for the cause of human rights in our world today.” Why is Washington’s Colombian war so different from yours?

A lot of Colombians probably agree with that, and would be happy to have their country seen that way. There are glimpses of concrete change, local political machinery being challenged. Still, Rice’s comment is wishful thinking, and something that we will achieve, but we’re not there yet. And there are things in the social, fiscal, educational and foreign policies, and in the legal world of the country, that need to change before we achieve this perfect state that she refers to.

The overarching narrative journey in your book is framed by encounters with a U.S. army serviceman called “Charlie” who has volunteered to go to Colombia because, as the son of a drug addict, he says he wants to “kill each and every motherfucking drug dealer with [his] own hands.” How does he fit into this story?

Charlie became an important part of my journey of going back and writing this book. He was going to Colombia as U.S. military, but also to fight his own personal war. When I met him he was on his way. After his time there, he recognized how much more complicated it is, and how [U.S. involvement in Colombia] creates more problems than it solves.

Colombia is seen as the country that has only drug problems. I am always surprised to see how little the fact that Colombia is a drug-producing country plays out in the day-to-day of politics, of the quotidian life there. Charlie realized this, and to me he represents Washington’s narrow focus and how they see this very complex country.

Are you saying that narcotics trafficking isn’t important in Colombia?

It’s not what carries the political discourse of Colombia. It is not what Colombians are preoccupied with, although it is a large part of how the country works.

Isn’t drug trafficking the source of the kidnappings, the violence, the injustice?

The violence in Colombia was not brought about by drug trafficking. We had a period called “La Violencia,” in the 1950s, for example. Colombia has a situation that is complicated by drugs, and although it’s important to focus on what effect drug trafficking has on Colombian society, I’m more interested in human dynamics, the relationships between employer and employee, between man and woman, teacher and student, government and citizen, artists and civil society. That’s what my book wants to show: how that Colombia works. A lot of the way people treat each other leads to me calling Colombia, [in the book,] “a fiefdom of dysfunction under one flag.”

In the book, you spend some time living at your grandmother’s in Barranquilla, a coastal capital, and find that you have very little in common. What makes you different?

My grandmother had this slew of granddaughters who were sent to American schools and wore clothes that were maybe a little inappropriate to her. She lived in a very rigid world where, if it wasn’t how her world worked, she was not interested, even if it was her grandchildren. So we lived these parallel lives, and in a way that’s a metaphor for Colombia: The feudal and the modern never sit down to talk at a table. Maybe we’re starting to now.

Since reporting this book, you’ve been researching the biography of an iconic figure of Latin American revolution, Che Guevara. Why?

I started without any intentions of getting so involved in the life of Che Guevara, but in 2001 I had taken a trip to Cuba. Things were different. There was a cultural relationship between Cuba and the United States, and as a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute, I had a license to go as a journalist.

I brought the three people who had just come out from doing the movie “Traffic”: Laura Bickford, the producer; Steven Soderbergh, the director; and Benicio del Toro, who won an Oscar for his performance. They had all informally spoken about doing a movie about Che Guevara. So now I’m writing a book on Che and also have been helping research and produce the film that we are shooting right now. Benicio del Toro knows so much about Che Guevara that together we’ve become almost like a research team, and we have visited and interviewed all the principal characters of the Che Guevara story who still live.

And you actually appear on-screen in the film?

About two years ago, we shot here in New York at the U.N. This was a trip that Che Guevara made to speak at the General Assembly in December of ’64. We wanted to re-create that visit, actually the last time he was seen in public. As we were going through all the archival material, literally three days before we started shooting, I saw a picture of Che sitting at the desk at the General Assembly, probably taken minutes before he went up to the podium to speak, sitting between two men, the ambassador and the secretary at the U.N. mission. And right behind him I saw this woman sitting with them.

When I looked at the script, we only had the two men in it. So I asked the director if there was any chance that a woman could be sitting there, and I asked him if it could be me. He said yes. That turned into a whole series of scenes with me as this woman [Cuban revolutionary leader Alba Griñan Nuñez]. But sometimes I think that Steven was just playing a joke on me, shooting with no film. You know, when you’re 4 years old and you tell your mother, “Oh, Mommy, take a picture of me!” and there’s no film in the camera? So I have to see if I make the cut.

You have been quoted as saying, “What I’m writing is like the nonfiction version of what Gabriel García Márquez did with ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude.'” (You even borrow the first three words, “Many years later…” for your opening.) What do you mean by that?

I call it “nonfiction magical realism.” Magical realism has become a way to describe a literature that lightens or makes quaint the problems and the dynamics of a society. For me magical realism prettifies the problems that we live with. I don’t think that was García Márquez’s intention, but I think that’s what it has become. Magical realist things, as they’ve come to be known in Latin American literature, happen in my reporting. The fact that there are [guerrilla-run] checkpoints [that lead to kidnappings] and that people call them “miraculous fishing” — that is an example of magical realism, but it’s true.