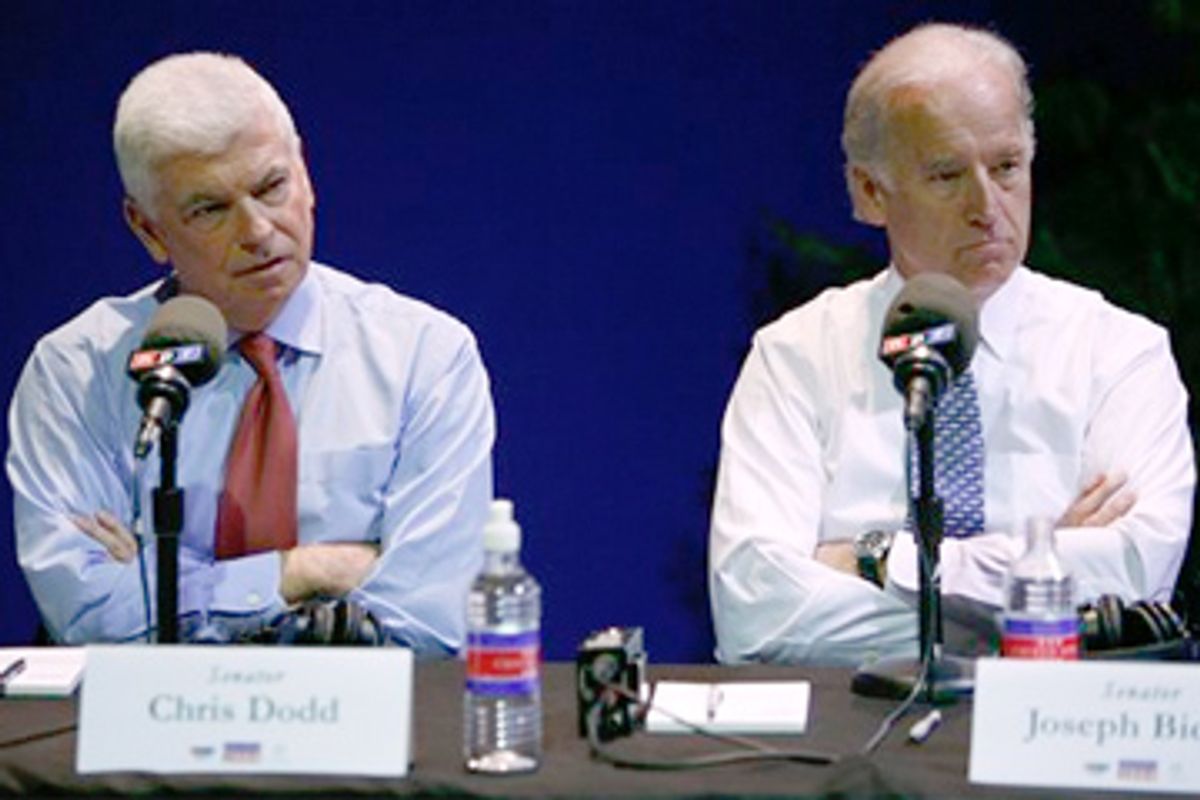

In politics, radio can be the great leveler. According to legend, the 5 o'clock-shadowed Richard Nixon won the first 1960 presidential debate against matinee idol John Kennedy among voters who only listened on radio. And for two hours on Tuesday afternoon on National Public Radio, those veteran foreign-policy experts Joe Biden and Chris Dodd dominated the penultimate Democratic debate before the Jan. 3 Iowa caucuses. As Barack Obama put it during a discussion of Chinese trade policies, "Chris and Joe made a good point."

NPR provided the perfect forum to highlight for a brief moment the overlooked strengths of these two long shots, who collectively have spent 66 years in the Senate. The potentially dismissive word "polls" was not uttered once during the debate. With radio, there is never the manipulative temptation to group Hillary Clinton, Obama and John Edwards at the center of a stage. But most important, this was the first candidate face-off that gave some of the knottier challenges of foreign policy the detailed attention they deserve.

Scoring a debate is an impressionistic exercise -- and others may not share my upbeat assessment of Biden and Dodd. (Here is an alternative grading system.) A cerebral afternoon radio debate devoted to just three topics (Iran, China and immigration) is not likely to move political markets, even with the caucuses less than a month away. Nor did it provide the zesty one-liners and snarky attacks that often shape press coverage.

But for two hours Tuesday afternoon, Biden and Dodd made the case that traditional political experience matters in choosing a president. From the subtleties of Iranian policy (where Biden excelled) to the nuances of academic studies on illegal immigration (where everyone deferred to Dodd), the two senators sounded knowledgeable in answering questions rather than as if they were reciting "Canned Debate Answer No. 623." Bill Richardson, the candidate with the most varied job history (congressman, energy secretary, U.N. ambassador and governor), missed the debate because he was attending a memorial ceremony to honor a Korean War POW whose remains the candidate had brought back to Iowa in April.

An intellectually intriguing moment in the debate came when four candidates were asked to enunciate the doctrine -- something akin to the Monroe Doctrine or Bush Doctrine -- that would define their foreign policies as president. Clinton took a predictable route as she discussed working through "multilateral organizations" and emphasizing "cooperation in our interdependent world." Edwards, who seemed thrown off stride by the question, groped his way toward vaguely suggesting that America's goal should be to demonstrate "that we respect people who have a different perspective than we do." Obama, after suggesting that the world is too complex for a one-size-fits-all doctrine, did go on to say, "We have to view our security in terms of a common security and a common prosperity with other peoples and other countries."

These answers were neither objectionable nor memorable. But Biden, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, was in his element, offering a big-picture answer. "We need a doctrine of prevention," he said. "The role of a great power is to prevent crises. And we don't have to imagine any of the crises. We know what's going to happen on Day One when you're president. You have Pakistan, Russia, China ... Afghanistan. You have Darfur. And it requires engagement and prevention."

In terms of Iowa, the clock has reached the "throw anything, maybe something will stick" point in the race, when even Obama's childhood claims that he "wanted to be president someday" have morphed into a campaign issue. But little from the NPR debate seemed to boast what in old-fashioned showbiz terms would be called "legs." Tellingly, there were no post-debate press release salvos among the rival campaigns.

In her strongest moment of an afternoon mostly devoted to avoiding mistakes, Clinton recalled one of the unquestioned triumphs of her tenure as first lady. "Twelve years ago, I went to China and the Chinese didn't want me to come," she said, referring to her attendance at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. "And they didn't want me to make a speech. And when I made the speech, they blocked it from being within China [because] I stood up for human rights and, in particular, women's rights."

Pressed to further explain her role within administration decision-making, Hillary replied, "I was deeply involved in being part of the Clinton team in the first Clinton administration." Her choice of language deserves parsing. Was the New York senator distinguishing "the first Clinton administration" from her own putative presidency? Or was she tacitly admitting that her policy role was minimized during the sad-eyed days of her husband's second term when the newspapers were filled with words like "infidelity" and "impeachment"?

In each debate, Edwards veers closer to directly attacking the Clinton presidency. "American trade policy is catering to the interests of big corporate America," he said Tuesday. "It has been for a decade and a half." The precision of Edwards' timetable was not accidental -- 15 Decembers ago Bill Clinton was poised to be inaugurated as president, with the enactment of NAFTA as one of his highest priorities. Something to watch in the closing days of the Iowa campaign is whether Edwards ever makes this high-risk critique explicit by directly tying both Clintons to NAFTA, or even goes as far as charging them with "catering to the interests of big corporate America."

NPR's gift to Iowa voters may have been creating the setting for the campaign's first "Experience Counts" debate. Tuesday's broadcast served as a reminder that the leading Democratic candidates all boast unconventional political résumés -- Clinton's eight dramatic years as first lady; Obama's three-year skyrocket from obscure Illinois state senator to top-tier presidential candidate; and Edwards' own rapid transition from trial lawyer to 2004 vice-presidential nominee. But as Biden and Dodd demonstrated -- during an afternoon that probably will be no more than a political blip -- there are benefits to a long apprenticeship on Capitol Hill for the presidency.

Shares