Mike Dennehy ran John McCain's successful 2000 campaign in New Hampshire and is working as a senior advisor for him now. He'll tell you that it's "crucial" for McCain to do well in New Hampshire this time around, and he'll tell you exactly how that's going to happen: "What it comes down to," Dennehy says, is having McCain spend "as much time as humanly possible in front of voters in town hall settings."

That means McCain had town halls in New Hampshire scheduled for Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday this week, that he'll be back for more before and after Christmas, and that he'll be campaigning in the Granite State on both New Year's Eve and New Year's Day and on a lot of days after that.

So how much time will McCain be spending between now and Jan. 3 in, say, Iowa? "I'd rather not comment on that," Dennehy says. "Let's just say that the overwhelming emphasis will be on New Hampshire."

Yes, let's just say.

There may be some way for John McCain to win the 2008 Republican presidential nomination without winning in New Hampshire, but I haven't heard anyone articulate one. Somewhere between the compressed primary calendar, the looming holiday season and the surprising surge of Mike Huckabee, the Republican race has become less like an ongoing drama that builds to some logical conclusion and more like a series of one-act plays -- each with a different cast -- that some way, somehow, someday leads to something. On Jan. 3, it's the Mike Huckabee show in Iowa. On Jan. 15 and Jan. 19, the ensemble gets a shot in Michigan, Nevada and South Carolina. Then comes Jan. 29, and the Mayor of 9/11 presents himself as the Next President of Florida. Skipping over Maine on Feb. 1, we find ourselves at Super Tuesday on Feb. 5, when 22 scenes in 22 states will lead either to a coronation or chaos.

New Hampshire? Ah, yes, New Hampshire. It's still the "first in the nation presidential primary" -- coming, as it does, five days after Iowa's "caucuses," three days after Wyoming's "conventions" and an entire week before the Michigan primary -- and it's the stage where McCain's up, then down, then up again campaign has to be up if he's going to be around for whatever happens afterward. If Huckabee rolls in Iowa and Mitt Romney wins big in New Hampshire -- and that's what the polls seemed to suggest just days ago -- then it's a maybe- waiting-for-Rudy two-man race. But if McCain runs tight against Romney or somehow overtakes him in New Hampshire -- a Rasmussen Poll out Wednesday has the senator from Arizona pulling within 4 percentage points of the former governor of Massachusetts -- then he's well positioned to regain some of his old luster in Michigan, where independents can vote in the Republican primary, and in South Carolina, where McCain can counter Huckabee's growing support among evangelicals, who may account for more than half of all GOP primary voters, with his own support from the state's large population of veterans. Romney becomes a very expensive two-time loser, Huckabee begins feeling like the flavor of last week, the money starts pouring in, and Rudy Giuliani never knew what hit him.

That's the plan, anyway, and that's why if it's Monday night -- a Monday night in which the only competition anywhere in New Hampshire is an appearance by Dennis Kucinich's wife -- John McCain must be here in Weare. Weare is pronounced "Where," and where Weare is, is about 20 miles east of Manchester. If there's much in Weare beyond a market and a couple of churches, it's hard to see what it is under a foot of snow. But what there is, is a town hall -- the Weare Town Hall -- and that's all McCain needs.

They've got the place set up for about 80 folks, but the crowd is big enough that campaign staffers in blue blazers and duck shoes are pulling folding chairs out of the closets as former New Hampshire Gov. Walter Peterson Jr. begins a long, long introduction of the candidate. It's long because McCain is running late, then it's long again because the videotaped tribute to McCain fades out mysteriously right when the young Navy pilot is about to die in Vietnam, and the governor, who's 85 and working with a microphone that doesn't work, has to keep ad-libbing the lines already ad-libbed while killing time before.

"Somebody throw me a lifeline," the governor begs at one point, but nobody can really hear him because Don Henley's "Boys of Summer" is blasting through the speakers. It is 19 degrees outside.

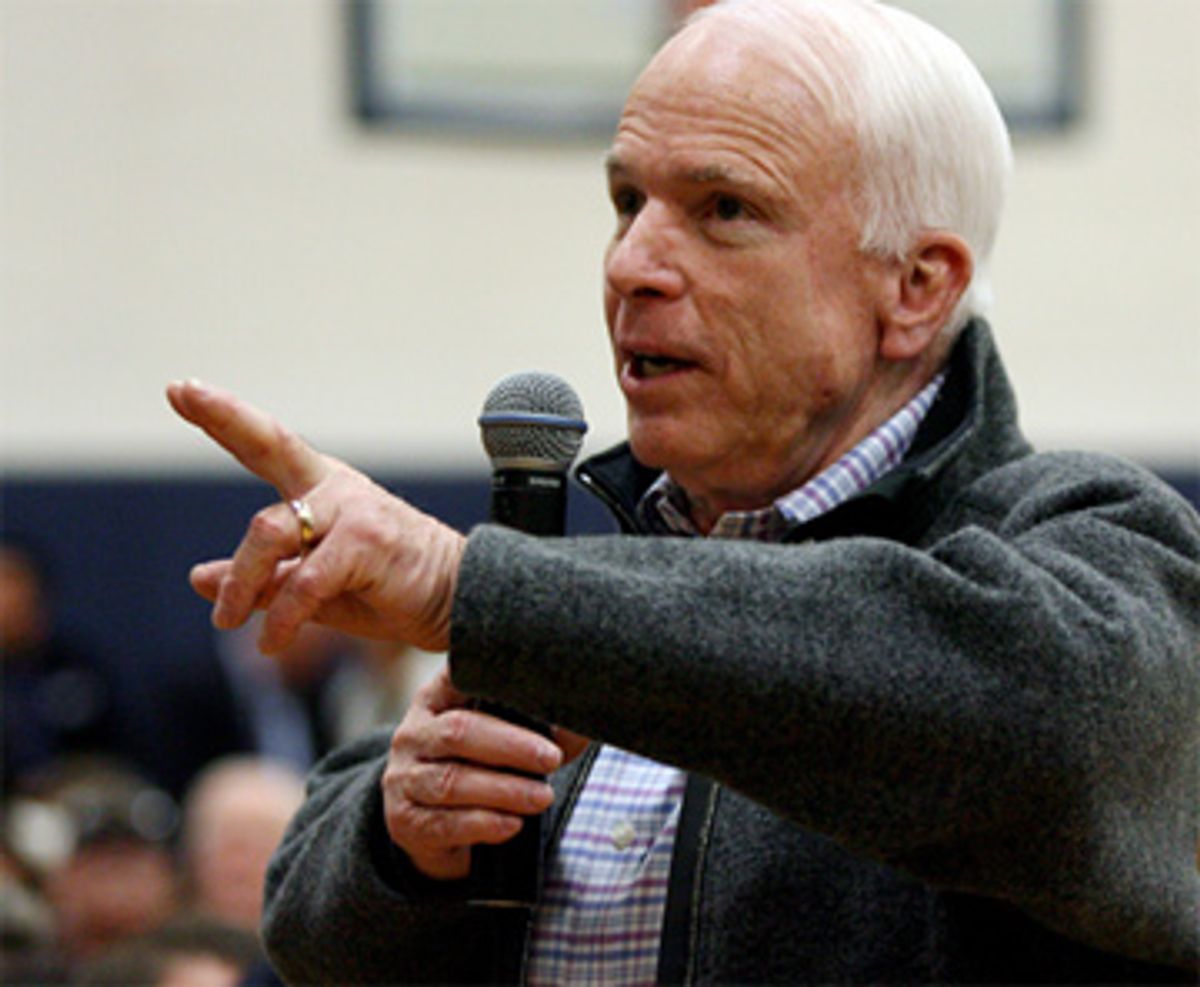

When McCain finally arrives at the back of the room, the campaign's sound system craps out totally. You can hear "Johnny B. Goode" off in the distance, as if it's bleeding through the headphones of somebody's iPod, and you can't hear the governor at all. McCain walks briskly to the stage, and suddenly you see the genius of it all: When you're introduced by a sharp but shuffling octagenarian, your sprightly 71-year-old self looks pretty good by comparison.

McCain doesn't hide his age on the stump. Maybe he couldn't if he wanted to, but it also seems like part of the appeal. In the year of Barack Obama and Huck-a-who, McCain -- who's served in Congress for the last 25 years -- neither needs to be nor can he be the "maverick" that he once was. As McCain jokes about the weather, his Arizona is still the Arizona of visitors' bureau postcards, all golf courses and sunny skies beckoning frozen snowbirds from the East. He tells one joke about Mo Udall -- the congressman died a decade ago -- and then he tells another. When the sound system keeps cutting in and out, McCain blames the Democrats, then jokes that the guy at the sound board is from the prison work-release program, then says there must be some "closet communists" running the thing.

Communists?

McCain asks for the house lights to be turned up so that he can see the folks who've come out to see him. But it seems just as likely that he needs the lights to make out what's written on his note cards, cards he uses so that he can know which local dignitaries to acknowledge and so that he can be sure to hit all the high points of his speech. "Speech" is a strong word for the talk McCain delivers; it's more of a list -- the economy, government spending, healthcare -- fleshed out with comments he invariably promises to make "very briefly." The "high points" are pretty far and few between, too; McCain's delivery is so flat that the applause lines, such as they are, sometimes pass without notice.

The citizens of Weare clap when McCain vows to fight to keep New Hampshire the "first in the nation" primary state, and they clap again when he claims he's never "sought or received" a pork-barrel project or earmark for Arizona. But it's quiet as McCain makes his way through the alternative minimum tax and his conservative bona fides, and it's quieter still as he discusses Iraq.

This is the odd spot for him. If McCain is the Republican candidate who holds the most appeal for New Hampshire independents –- they are 45 percent of the electorate and can vote in whichever primary they like on Jan. 8 -- he's also the one whose views on the war might be the least attractive for them. While a lot of other GOP contenders try to say as little as possible about the war, McCain makes it a centerpiece of his appeal. McCain says he was right all along when he argued that the United States needed more troops on the ground, and he clearly feels vindicated by whatever military success the "surge" is producing now. If the folks in the hall have paid attention, they know that McCain hasn't been as consistent on the war as he suggests. And even if they haven't, they're pretty clearly ambivalent about the idea of keeping large numbers of troops in Iraq for however long McCain thinks they need to be there. McCain mentions the "brave young Americans" serving in Iraq three times before anybody thinks to offer the obligatory respectful applause.

But McCain isn't about the applause, a point made clear as he segues into the question-and-answer part of the evening. When a charming old crank in a veteran's cap asks McCain about a report that Hershey's is closing plants and outsourcing some of its chocolate production -- "I don't want to eat Mexican chocolate," he says -- McCain sympathizes but then counters that lowering tariffs on foreign sugar will make the man's candy bars cheaper. When a woman asks about immigration, McCain explains why he backed immigration reform, why he thought it had failed -- the American people didn't trust Washington -- and then pushes back by saying that we still need a plan that treats people as "children of God."

Toward the end of the night, a man in the back rises to ask about the injustices of the war. What he has in mind: the way in which the Marines allegedly involved in atrocities in Haditha faced prosecution while the New York Times goes unpunished for publishing information that puts the troops at risk. The man is honestly saddened by what he's discussing; his voice cracks with emotion as he speaks. McCain's response: He says nothing at all about the Times, and he says he's glad that U.S. troops are held accountable for their actions when they've appeared to have crossed the line.

Is this a way to win the presidency? Maybe so. McCain's grown-up approach won him the endorsements of the Des Moines Register and the Boston Globe last weekend, and Joe Lieberman's sort-of across-the-aisle endorsement Monday has brought a new wave of media attention to a campaign that was left for dead this summer. McCain's people hope that his old-school approach will speak to New Hampshire voters looking for a safe choice -- that he'll be, in Peterson's words, a candidate who "wears well."

"I think he's settled on a message," says University of New Hampshire political scientist Dante Scala. "Last time, he was the maverick candidate. This time, he's coming across more as the reliable candidate, the reliable commander in chief. I think that plays with folks." With Giuliani's "star falling," Scala says that "there's no one between McCain and Romney right now," and he gives the underdog a "fighting chance" of coming out on top. "That said, my sense is that McCain is going to need some help, and that's going to be in the form of a Huckabee victory in Iowa and probably a pretty big victory in Iowa that presents Romney as damaged goods to New Hampshire voters."

The Romney campaign is working hard to prevent that scenario. Romney will be splitting his time pretty evenly between Iowa and New Hampshire over the next couple of weeks, and Romney spokesman Kevin Madden downplays what he calls McCain's "quote-unquote surge." "McCain was the president of New Hampshire, and he ought to be doing a lot better," Madden says. "Early on in the year he was [polling] in the 40s, and everyone was pointing to that as strength. Now he's in the high teens and 20s, and it's being labeled a surge. There's a structural deficiency there."

Shares