The top-grossing movie of 2007 was Sam Raimi's "Spider-Man 3." But we're not here to talk about that. Nor are we going to trouble ourselves much with "Shrek the Third," "Transformers," "Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End" or even the perfectly satisfying "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix," which round out the top five.

Box-office receipts have become a large part of how we look at movies, and they do matter somewhat, since they partially dictate what kinds of movies we'll be seeing in the years to come. But they have nothing to do with how we actually feel about movies. The terrible and wonderful truth is that people who still bother to venture out to movie theaters (you know who you are) might very well go to see "Spider-Man 3" if they were fans of the first two pictures, or if their friends say it's good, or even if they just need an evening of mindless entertainment.

But far more interesting patterns emerge when moviegoers look back on the year and think of the movies they took the trouble to see, the ones they wanted to see and missed, the ones that dashed or exceeded their expectations. Those wonderfully rangy and idiosyncratic lists say more about what we hope for (and either do or don't get) when we go to the movies than any number of box-office statistics can.

I recently met a young writer who, having decided he didn't know as much about movies as he wanted to, put together a film course for himself via his Netflix queue, a way to work through the likes of Godard and Chaplin, Fellini and Hawks, Hitchcock and Renoir. We talked about Netflix queues not just as lists of titles but as dream outlines of the people we'd like to be -- you, or I, might be a person who watched "Masculine Feminine" three times before returning it; who had every intention of getting through "Hiroshima Mon Amour" but ultimately sent it off in the pouch, unwatched; who is glad to have seen "The Passion of Joan of Arc" but also relieved at the prospect of never having to watch it again. Through movies, we collect bits of ourselves, and sometimes we reject parts of ourselves, too.

So in the context of the movies many people didn't choose to see this year, what do we make of the numerous pictures that attempted to deal, directly or otherwise, with the Iraq war? Nearly every critic I know wrestled with what the mere existence of these movies meant, as well as with what they might mean to individual viewers and to the culture at large. Maybe it's great that these movies got made in the first place. But what does that matter if they're no good -- or if no one goes to see them? Countless publications ran articles and essays speculating about why audiences weren't turning out in large numbers for pictures like "In the Valley of Elah" and "Rendition." At Salon, we had a staffwide e-mail discussion about whether there was a way to write a reported piece on why these movies failed to attract audiences.

I don't think it's possible for anyone to come up with a definitive answer. One portion of the explanation might lie in the fact that most of the Iraq war-related movies were rated R, not PG or PG-13, which automatically trims their potential audience. Ultimately, the slender turnout for these movies may point to a larger and knottier problem: American moviegoers aren't necessarily turning away from the war as a subject. It could simply be that the audience for any kind of serious adult drama has shrunk, period -- after all, it's been shrinking for years.

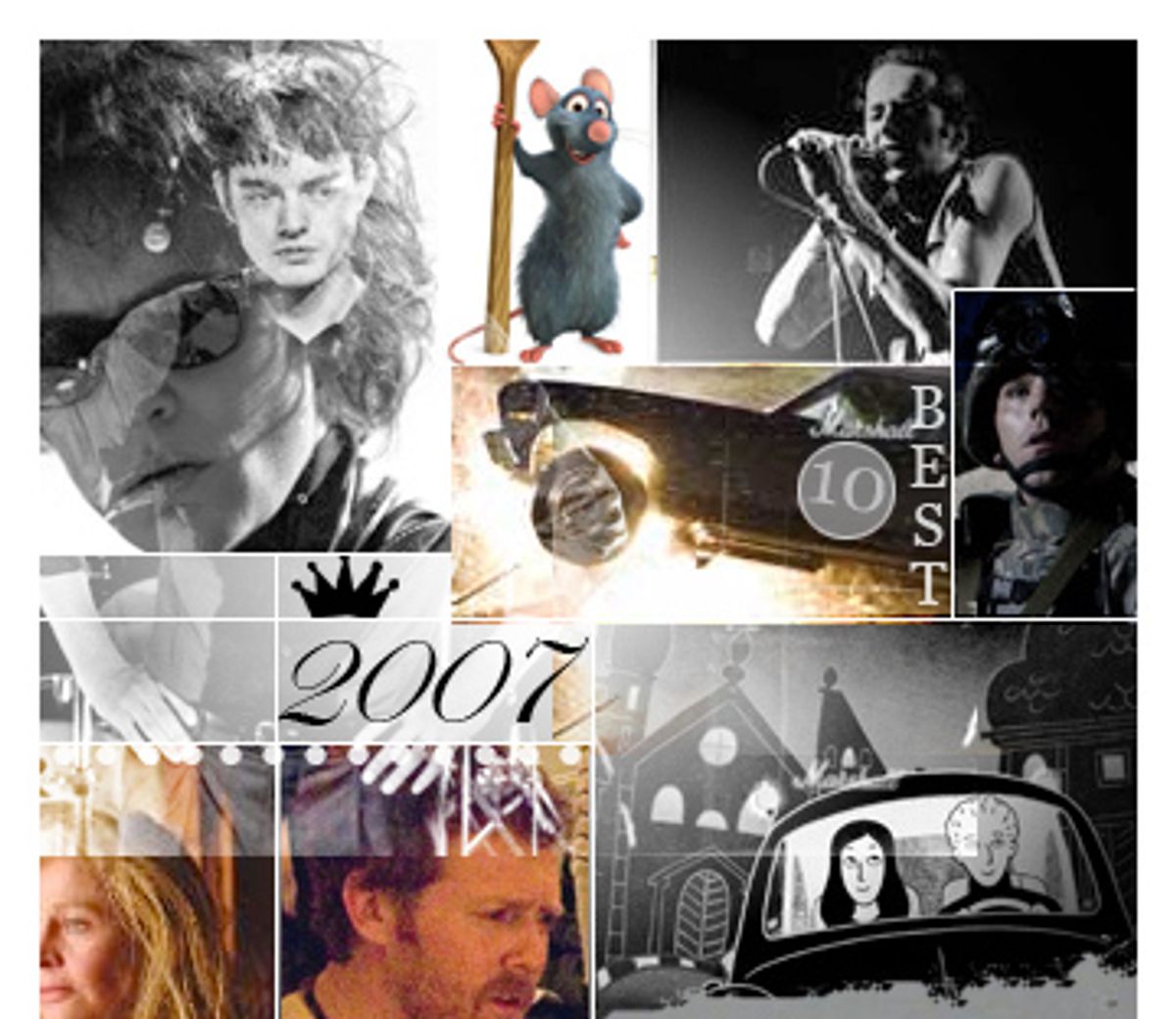

Of course, some of those "movies no one saw" were worth our time: My own thoughts about that are reflected in my top 10 list, below, as well as in the sprawling list of also-rans that follows it. And while I can't get on the creaky-wheeled existentialist "No Country for Old Men" chuck wagon, I'm willing to concede that it at least allows people to think it's a movie made for grown-ups. Then again, "Ratatouille," which is about a cartoon rat who finds his true calling in the kitchen of a Paris restaurant, really is a movie for grown-ups, and for everyone else. What follows is a list of my favorite movies of the past year, somewhat in order of preference, although beyond the top three I always find making such distinctions difficult. (Check back later this week for my colleague Andrew O'Hehir's top 10 list.) These are all pictures that moved me, delighted me, surprised me or left me devastated in 2007.

"I'm Not There" -- Todd Haynes' dream-meditation on the idea of Bob Dylan is a ballad sung in the language of movies, as if the only way to get to the meaning of Dylan were through another type of song. Cate Blanchett plays Dylan -- one version of Dylan named Jude Quinn -- as a charismatic, neurotic, sexually alluring imp, a changeling, a bundle of receptors half-open to the world and half-guarded from it. She -- he -- is solitary, transfixing, beautiful beyond belief.

"Control" -- Rock 'n' roll portraitist Anton Corbijn makes his feature debut with a straightforward and openhearted picture about Ian Curtis, the lead singer of Joy Division, who committed suicide in 1980. The movie works, quite simply, as a story about a gifted and deeply troubled young guy who just couldn't hold it together: Sometimes the stories you think you've heard a million times before are merely universal. Shot in satiny black-and-white by Martin Ruhe, it's also the most stunning-looking film of the year.

"The Diving Bell and the Butterfly" -- Julian Schnabel adapts the unadaptable, the 1997 memoir of the late Jean-Dominique Bauby, who was rendered almost completely paralyzed by a stroke. The picture is so imaginatively made, so keyed in to the indescribable something that makes life life, that it speaks of something far more elemental than filmmaking skill: This is what movies, at their best, can be.

"Persepolis" -- Marjane Satrapi's two-volume graphic memoir, which recounts, among other things, her childhood first in pre-revolutionary Iran and then under the repressive fundamentalist regime, is the kind of work that easily closes the gap between the people who read "comics" and the people who don't. This animated adaptation -- directed by Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud -- brings the striking austerity of Satrapi's black-and-white drawings to life on the screen. The picture is intimate, as an autobiographical work ought to be, but it's also panoramic in scale: It captures the way people's lives can be drastically changed and yet, in some ways, remain defiantly unchanged when their government subverts everything they believe in, using God -- or some version of God -- as its chief weapon.

"Away From Her" -- Canadian actress Sarah Polley makes her directorial debut with a carefully made, intimate picture (based on a story by Alice Munro) about a woman who, having been diagnosed with Alzheimer's, moves into a nursing home, where she drifts away from the husband who still loves her and falls for another patient. Julie Christie and Gordon Pinsent both give astonishing performances, in a picture that's less about illness than about the intricacies of marital loyalty.

"Ratatouille" -- Brad Bird, one of the great modern animators, gives us one of the most beautiful-looking animated movies ever made, about a Parisian rat who becomes a chef. This is a practical-minded picture, a story that's less about dreams than it is about work. But it's also about the delight that work, done well, can bring.

"Grindhouse" -- Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez deliver an affectionate and recklessly joyous double-feature homage to cheap exploitation movies, and to the idea of movies as communal pleasure. In "Death Proof," partly an homage to car-chase pictures like "Vanishing Point," Tarantino does everything the old-fashioned way, with fast cars and real human beings doing crazy things; it's elegiac in a perverse, twisted way. And the visual surface of Rodriguez's feature, "Planet Terror," is intentionally scraped and scratched, faded and discolored, made to look as if it had been run through too many ancient, badly maintained projectors. Those faux scars suggest the way movies -- lousy ones as well as good ones -- endure: In our memories, they outlive the fragile celluloid on which they're captured.

"Once" -- The story of two people falling in love should be the simplest kind to tell, but it's also the easiest to botch. Everything about this modest, unassuming sort-of musical by the Irish filmmaker John Carney feels unforced and natural. He allows his actors, Glen Hansard and Markéta Iglová, to guide the picture through its gently shifting moods.

"Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten" -- We all feel residual fondness for the music that meant something to us when we were young -- how can we not? But Julian Temple's exuberant and deeply moving documentary about the late Clash frontman is more than just a nostalgia fix for the late-baby-boomer set. It understands that punk, at its best a vibrant and vital form of protest music, was a "yes" that only sounded like "no." And Temple captures how Strummer in particular -- an artist whose sensibility was big enough to enfold the MC5, Elvis and Woody Guthrie -- proved that inclusivity and community weren't just the province of the Woodstock generation.

"No End in Sight" and "Redacted" -- Pauline Kael once said, "If movies aren't entertainment, what are they -- work?" But she knew as well as anyone that some movies demand more of us than we may willingly want to give, and opening ourselves up to them is a kind of work. Of all the Iraq war-related pictures released this past year, these two are essential: Charles Ferguson's "No End in Sight" is documentary as nightmare, a clear-eyed explanation of how we got into the Iraq mess in the first place, but more important, a grim reminder that there's little hope we can extricate ourselves without failing the very people we were supposedly trying to help. Brian De Palma's "Redacted" is a nightmare posing as a documentary, a fictional story based on true events (most significantly, the rape and murder of a 14-year-old Iraqi girl in 2006 by American troops) that challenges us to question how we process -- or fail to process -- whatever information we get from the media. Events unfold in ways that are sometimes confusing, contradictory, not immediately readable; the movie's structure alone is a metaphor for the struggle to make sense out of chaos. This is a picture that's electric and alive, so loaded with feeling that it's sometimes difficult to watch, but De Palma makes turning away impossible.

AND MORE: Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's "The Lives of Others," Apichatpong Weerasethakul's "Syndromes and a Century," Mike Nichols' "Charlie Wilson's War," Johnnie To's "Exiled," Joe Wright's "Atonement," Craig Brewer's "Black Snake Moan," James Gray's "We Own the Night," Michael Winterbottom's "A Mighty Heart," Zoe Cassavetes' "Broken English," Judd Apatow's "Knocked Up," Greg Mottola's "Superbad," Jason Reitman's "Juno," "Paris je'taime" (multiple directors), Julie Delpy's "2 Days in Paris," Kasi Lemmons' "Talk to Me," Paul Verhoeven's "Black Book," George Hickenlooper's "Factory Girl," Matthew Vaughn's "Stardust," Francis Lawrence's "I Am Legend," Robert Redford's "Lions for Lambs," Paul Greengrass' "The Bourne Ultimatum," James Mangold's "3:10 to Yuma," Steve Bendelack's "Mr. Bean's Holiday."

Shares