For the hundreds of thousands of poor Southern blacks who made the trek north in the early 20th century, Chicago was literally known as the promised land. It promised prosperity, relative freedom -- and also, incredibly, political power. When the sharecroppers of Alabama and Mississippi passed around copies of the nation's biggest black newspaper, the Chicago Defender, in the 1920s and '30s, they read about a city with something unheard of in the rest of America: a black representative in the U.S. House. Oscar S. De Priest was a Republican, loyal to the party of Lincoln, and as the lone black man in Congress, he ended discrimination in the Civilian Conservation Corps, filed anti-lynching bills, and integrated the Senate Dining Room, over the physical objections of an Alabama senator.

De Priest was defeated in 1934, after the New Deal converted blacks to the Democratic faith, but his seat has remained in African-American hands ever since. It's currently held by Bobby Rush, a former minister of defense for the Black Panther Party.

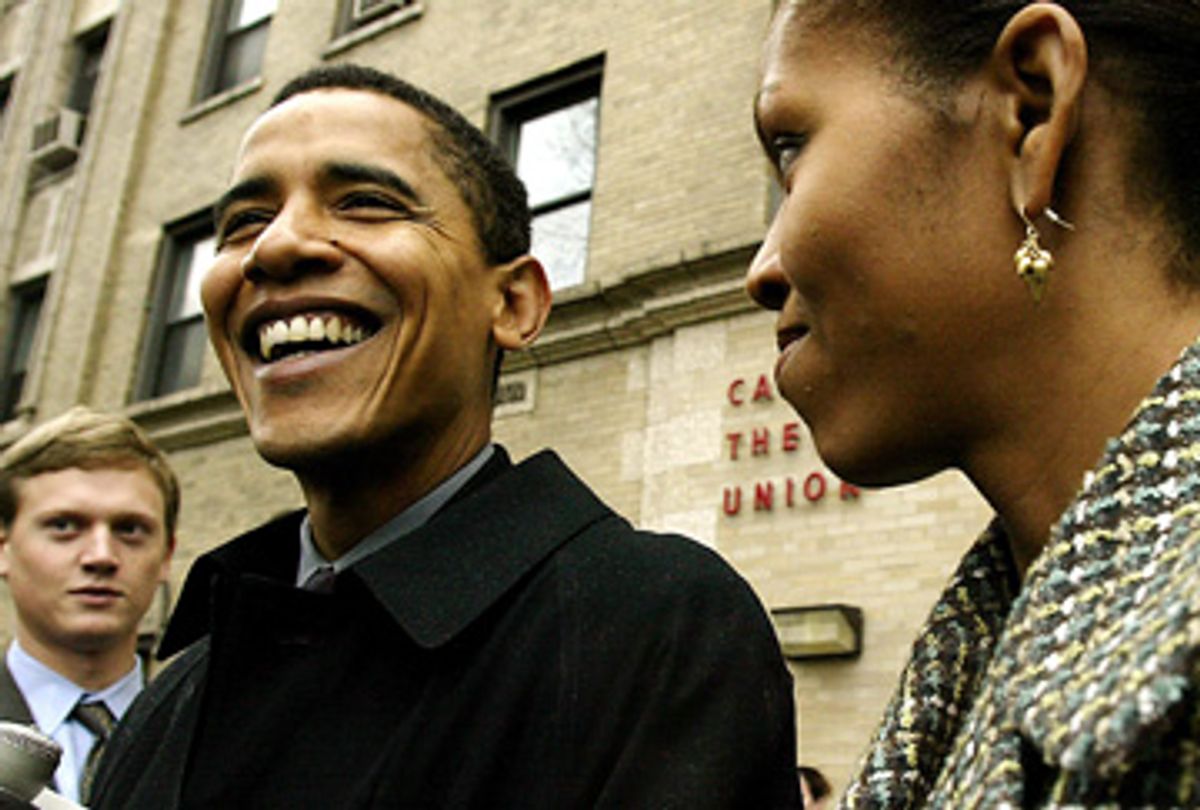

When Barack Obama was 22 years old, just out of Columbia University, he took a $10,000-a-year job as a community organizer on the South Side of Chicago. It was a shrewd move for a young black man with an interest in politics. Had he stayed in New York, "you would never have heard of him," says Lou Ransom, the Defender's current executive editor. "He may have been a very good lawyer and maybe got elected to some office, but if he hadn't come to Chicago, he would not have had the kind of support to push him where he is now."

His home state of Hawaii is more diverse, the California of his early college days is more tolerant, New York is more sophisticated. But only in Illinois could Obama have become a senator and a presidential candidate. Going all the way back to Oscar De Priest (and in some ways to Abraham Lincoln), Illinois has led the nation in black political empowerment. It has elected two of the three black senators since Reconstruction -- Obama and Carol Moseley Braun. It's had a black attorney general, and its black secretary of state is setting a new standard for that office by not taking bribes (or at least not getting caught). The only other black candidate to win a presidential primary was Jesse Jackson, who came to Chicago from the South as a seminary student and stuck around to build his own political machine.

Ironically, Chicago became the political capital of black America because it was so racist. For most of the 20th century, it was the most segregated city in America. Blacks used to have a saying: "In the South, the white man doesn't care how close you get, as long as you don't get too high; in the North, he doesn't care how high you get, as long as you don't get too close." During the Great Migration, the refugees who rode up from Mississippi on the Illinois Central Railroad were crowded into the Black Belt, the South Side ghetto portrayed in Richard Wright's "Native Son." Because the black population was so concentrated, white politicians couldn't gerrymander it out of a congressional seat. One of De Priest's successors, William Dawson, was the most powerful black politician in America. He helped boot out the predecessor to Mayor Richard J. Daley, the current mayor's father, who bossed Chicago from 1955 to 1976. In return, Daley's machine rewarded Dawson with control of the entire South Side.

The politician who truly set the stage for Obama's rise was also a South Side congressman: Harold Washington, who was elected mayor of Chicago in 1983, beating two white opponents in the Democratic primary -- incumbent Mayor Jane Byrne and future Mayor Richard M. Daley. In the general election, the difference between Washington and his Republican opponent was black and white -- and nothing else. When Washington campaigned at a church in a Polish neighborhood, he was greeted with the grafitto "Die, Nigger, Die."

In New York, Obama read about Washington's victory and wrote to City Hall, asking for a job. He never heard back, but he made it to Chicago just months after Washington took office. In his memoir "Dreams From My Father," he wrote about walking into a barbershop and seeing the new mayor's picture on the wall. (It's probably still there. To this day, Washington's image is as revered by South Side blacks as St. Anthony of Padua's is by Italian Catholics.) The old men, who'd suffered a lifetime of slights by white mayors, saw in Washington a sign that the black community had finally arrived as a citywide power. Blacks may have run things in their own neighborhoods, but they were still crammed into dreary housing projects, and they sent their children to overcrowded schools -- while white schools just across the color line sat half empty. And of course, the big political jobs -- the state's attorney, the County Board president, the mayor -- had always been controlled by the Irish.

"Before Harold," the barber said, "seemed like we'd always be second-class citizens."

After too many triple cheeseburgers and deep-dish pizzas, Washington dropped dead of a heart attack in his second term. But the confidence he instilled in black leaders became a permanent factor in Chicago politics. His success inspired Jesse Jackson to run for president in 1984, which in turn inspired Obama, who was impressed to see a black man on the same stage as Walter Mondale and Gary Hart. Washington also strengthened the community organizations in which Obama was cutting his teeth, says Ransom. Obama's Project Vote, which put him on the local political map, was a successor to the South Side voter registration drive that made Washington's election possible.

"Everybody owes something to Harold Washington, because that was something they never thought could happen," Ransom says. "If Harold can be mayor, what can't we do? Obama talks about the audacity of hope. That audacity has grown into the notion that a black man can be president of the United States."

Before Washington, a black Chicagoan pol's highest aspiration was U.S. representative. After Washington, it became senator, and finally, president. Plenty of other cities have had black mayors -- Detroit, Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, New York, Los Angeles, Cleveland, Baltimore -- but in none of those places have blacks achieved as much statewide political success. Chicago has two unique advantages, says political consultant Don Rose. First, it's in Cook County, which contains nearly half of Illinois' voters. Second, the local Democratic Party is a countywide organization. After Chicago's Carol Moseley Braun beat two white men to win the 1992 Democratic Senate primary, precinct captains in white Chicago neighborhoods and the suburbs whipped up votes for her in the general election.

"They had to go out and sell the black person to demonstrate that the party was still open," says Rose, who sees "direct links" from Washington to Moseley Braun to Obama.

"It was a hard-fought thing. If you use Harold Washington's election as the pivot point, what you begin to see is black politicians making challenges to the regular organizations, and then the organizations having to support them."

The other, non-Cook County, half of Illinois also plays an important role. When Obama stood before the Democratic National Convention in 2004 to deliver the keynote address, he kicked off his speech with a nod to "the great state of Illinois -- crossroads of a nation, land of Lincoln." That wasn't just a shout-out to the home folks. It was an acknowledgment of how the entire state had placed him on that stage.

Much as it dominates Illinois, Chicago can't elect a senator by itself. Black candidates also need support in downstate Illinois, which happens to be a region with a history of working out racial questions for the rest of the country. The prairie towns still cherish the legacy of Abraham Lincoln. When I lived in Decatur, smack in the middle of the state, I drank in the Lincoln Lounge, passed a courthouse statue depicting Lincoln as a young lawyer, and fished in the Sangamon River at the Lincoln homestead, west of town. It's no coincidence that two Illinoisans ended slavery -- Lincoln, by signing the Emancipation Proclamation, and Ulysses S. Grant, by accepting Lee's surrender at Appomattox. Before the Civil War, Illinois was evenly divided between Southerners who'd migrated up from Kentucky and Tennessee, and Yankees who'd reached the state through the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes. More than a generation before the rest of the nation took up the dispute, Illinois held a bitter plebiscite on slavery. The southern counties voted aye, the northern counties nay. The argument was continued in the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. In his Senate primary, Obama finished second downstate, but ran well in central Illinois, where Lincoln had traveled as a circuit-riding lawyer. He even won Lincoln's hometown of Springfield.

"It's clear that white voters in this state are willing to vote for qualified black candidates statewide," says John Jackson of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University. "You just don't find very many states where white voters are willing to vote for black candidates." Part of it is Chicago's ability to groom those candidates, part is the moderate character of the state's Republicans and independents, and part is the Yellow Dog Democratic vote in poor, rural southern Illinois, Jackson says.

Later, when Obama faced Alan Keyes in the nation's first black-on-black Senate contest, columnist Amity Shlaes wrote that "Illinois has a record as host to such innovation" and was "yet again emerging as the venue for a shift on race."

It was an election in which skin color was not an issue, won by a black candidate who has shown unprecedented appeal to white voters. That Illinois would become the birthplace of post-racial politics was no surprise to Obama. Early in his Chicago years, he realized his adopted home was a perfect training ground for solving America's problems, racial and otherwise. Last year, the Associated Press crowned Illinois "most average state" because its demographics so closely match the nation's. The United States is 13.4 percent black. Illinois is 14.9 percent black.

"Part of what attracts me about Illinois generally is I think it's a microcosm of the country: north, south, east, west, black, white, urban, rural, southern, northern," Obama once said. "For somebody who cares deeply about the country, and about the issues and struggles this country's going through, I can't think of a better laboratory to work on some of the pressing issues we confront."

Barack Obama came to Chicago decades after the Great Migration, but for a young black man with political ambitions, it still turned out to be the promised land.

Shares