Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1999

"Sorry, it's too dangerous," says the driver.

To the best of my knowledge and experience, Port-au-Prince is the only place in the world this side of Baghdad where a cabbie will refuse a $20 bill to take a pilot into town for a quick, drive-through tour. Where else? Maybe Monrovia, Liberia, or Freetown, Sierra Leone, during the wars in those countries.

With nothing else to do I wander the apron. Behind our dormant jet a row of scarred, treeless hills bake in the noon heat, raped of their wood and foliage for firewood by a million hungry Haitians. The island of Hispaniola is shared in an east-west split by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The border between these countries is one of the few national demarcations clearly visible from 35,000 feet -- the Dominican Republic's green tropical carpet abutting a Haitian death-scape of denuded hillsides the color of sawdust.

In front of the terminal, men ride by on donkeys and women balance baskets atop their heads. Somebody has started a cooking fire on the sidewalk. Haiti is the poorest country in the entire Western Hemisphere, and I can see more squalor along the airport perimeter than I saw in almost three weeks in the depths of southern Africa.

I notice a pair of large white drums being unloaded from our airplane. Something doesn't look right -- crew-member intuition -- and concerned that we'd accidentally transported some kind of hazardous material, I ask a loader if he knows what the barrels contain. A forklift carries them to a corner of a ramshackle warehouse, and three skinny helpers pry off the heavy plastic lids. What's revealed is a tangled white mass of what appears to be string cheese floating in water. A vague, quiveringly rotten smell rises from the liquid. The forklift driver sticks his hand in and gives the ugly congealment a churn. "For sausage," he answers. What we're looking at, it turns out, is a barrel full of intestines -- casings bound for some horrible Haitian factory to be stuffed with meat. Why the casings need to be imported while the meat itself is apparently on hand, I can't say, but somebody found it necessary to pay the shipping costs and customs duties to fly a hundred gallons of intestines from Miami to Port-au-Prince.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The story above is cut from the manuscript of a book I've been hoping to sell -- a memoir of sorts that I've titled "Half the Fun." It describes an afternoon several years ago, when I was a cargo pilot for DHL. The setting is the Port-au-Prince airport in Haiti -- a country I've never been to.

Wait, you say, hold on a minute. How could I have been to the Port-au-Prince airport but not to Haiti? Well, exactly that: I have indeed flown into the Port-au-Prince airport several times. But as far as I'm concerned, seeing that I never set foot outside the terminal, I have not been to Haiti.

The issue here is what, exactly, constitutes a visit to another country. Making that determination can be tricky, and those who travel a lot will occasionally wrestle with this quandary. When your plane stops for refueling or you spend the evening at an airport hotel, does that count?

Where to draw the line is ultimately up to the traveler; it's more about "feel" than any technical definition of a border crossing. But there should be a certain, if ineffable standard -- along the lines of that you-know-it-when-you-see-it definition of pornography.

According to my own criteria, a passport stamp alone doesn't cut it. At the very least, a person must spend a token amount of time -- though not necessarily an overnight -- beyond the airport and its immediate environs. For instance, in addition to the example of Haiti, back when I flew cargo planes, I stopped for refueling on three or four occasions in Guatemala City. But I never had time to venture beyond the terminal. On the pin-studded map that hangs in the dining room of my apartment, there was no pin for Guatemala.

Other cases, though, are more subjective. For instance, traveling once between Germany and Hungary, I spent several hours riding a train through Austria. We pulled into Vienna in the middle of the night and sat for six hours. At sunrise we headed out again, trundling across the Austrian countryside toward Budapest. Certain people might consider that enough, but there are no pins for Austria on my map. I saw towns, cars, people ... but all through the window of a train, never touching soil.

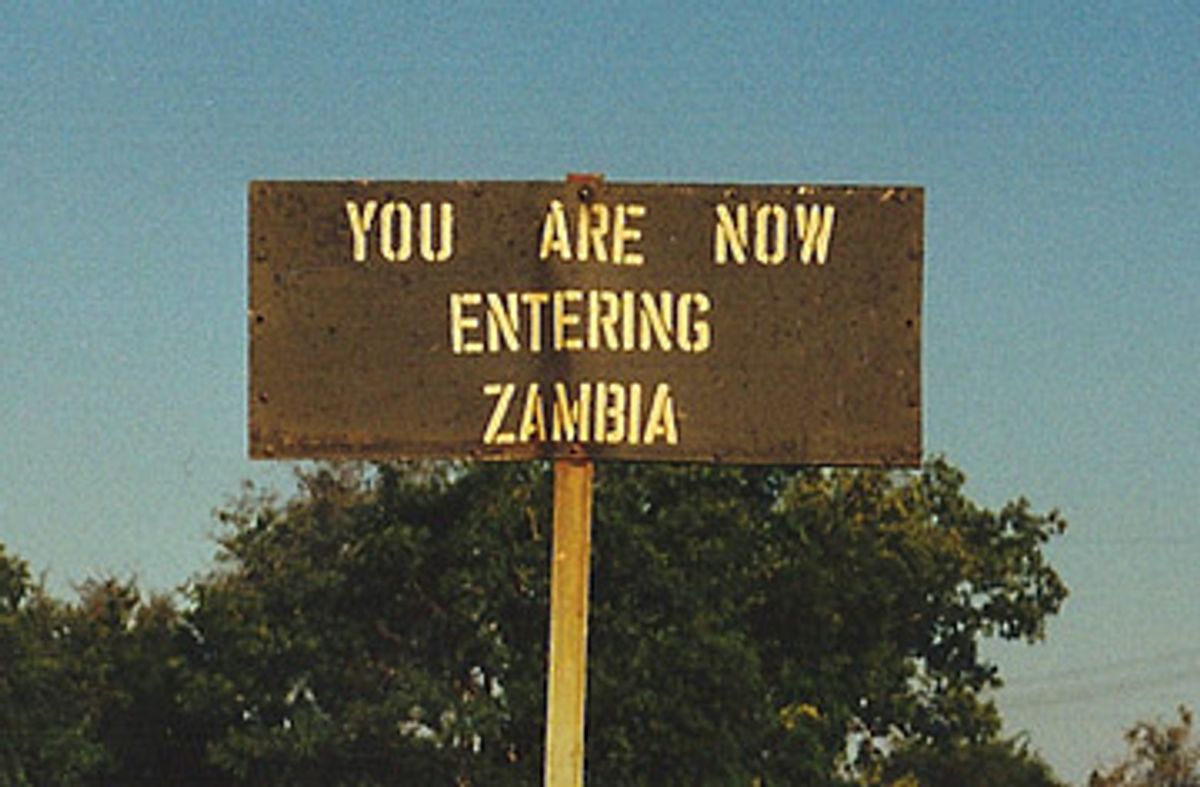

Trickier is the evening I spent camping "in" Zambia. We'd been traveling around Botswana for a couple of weeks, headed toward Victoria Falls. One afternoon we took a motorboat up the Zambezi River to a tiny wooded island, where we pitched our tents and spent the night. On the map this was Zambian territory; I had Zambian mud in my shoes. But we saw no villages and only a handful of people. I experienced nothing that could differentiate that portion of the river from the Botswana side only a few kilometers behind us.

Making things more difficult was the "You Are Now Entering Zambia" sign posted on the Victoria Falls Bridge. The famous span, from which dozens of bungee jumpers hurl themselves daily, straddles the Zambezi; one bank belongs to Zimbabwe, the other to Zambia. (I dare you to find a sentence with more Z's in it.) Up along the rail, watching the bungee jumpers drop headfirst toward the frothing white water, I must have stepped across that border 15 times. But have I actually been to Zambia? Nah.

On the other hand, I have been to the Dominican Republic (see below), albeit for just a few hours. Our flight was scheduled for a quick turn at Santo Domingo's Las Americas airport, but a cargo door malfunction gave me the break I needed. After changing out of my uniform, I found a driver who, unlike his colleague in nearby Haiti, was more than happy to take me for a spin through his country's historic capital, with two or three stops along the way.

Sometimes, though, the country itself is what muddles things up. Consider the world's various territories, protectorates, self-governing autonomous regions, occupied lands and quasi-independent nations. Yeah, I know, Vatican City is a sovereign state, politically speaking. But in practical terms, is it really? Did my visits to Hong Kong count as visits to China? What about Tibet? Western Sahara? Sure those are foreign nations, but which ones? Etc.

And let's not begin to assess the countless atolls, archipelagoes and assorted tiny islands scattered throughout the oceans. If a citizen of Japan visits Guam, has he been to the United States? In one sense, sure. In another, perhaps more accurate sense, he has simply been to Guam -- neither genuine U.S. turf nor a country unto itself. You can make a similar argument with Bermuda, Tahiti and elsewhere. Sometimes, maybe, there is no country.

Together these things can make it impossible to provide a wholly accurate answer when asked how many countries you've traveled to.

Of course, that's only important if you're the sort who keeps track of such things. For better or worse, there are those of us who know exactly how many nations we have visited. Hardcore travelers are known to hold "passport parties" upon reaching certain milestones -- a 50th, 75th or 100th country. In the eyes of some, country counting cheapens the act of travel by boasting quantity over quality, but that's just sour grapes. Bird-watchers aren't chided for their "life lists," so why begrudge a traveler his or her maps and pins?

I have met only one Hundred Country Club member in my life -- a pilot whose job flying VIP transports for the Air Force took him pretty much everywhere. Ironically and unfortunately, he was also the type who could not have cared less if he never set foot outside the United States. Pilots can be like that. I have known plenty of airline pilots who, despite being able to fly for next to nothing, have never been outside the U.S., and would not own passports if their employers did not require them to.

Anyway, with all of this in mind, it strikes me how the conveniences of modern jet travel -- specifically the invention of the enclosed jetway and the in-terminal hotel -- have made it possible to construct extended international journeys, as it were, stopping in any number of countries for a theoretically limitless amount of time, without once stepping outside. Get off the plane; stroll to the adjacent hotel; spend the night; stroll back to the gate for the next leg; repeat as necessary.

So I'm challenging readers to come up with the most elaborate, multistop itinerary possible that does not entail making contact with fresh air or touching local soil. Ideally, this perverse nonadventure will circle the globe and include a minimum of one night's layover on each continent. Participants may not leave the confines of an airplane, terminal or in-terminal hotel. Walkways to and from hotels are allowed, provided they are fully enclosed.

The winner will be forced to actually undertake this bizarre journey, dining nightly on authentic "local" cuisine from room service.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 1999

Thirty-three minutes away is Santo Domingo, the filth-and-stucco capital of the Dominican Republic -- or the D.R., as savvy travelers and baseball announcers love to call it. The neighborhoods around the airport are some of the poorest on the island, and we're two days on the heels of a terrible storm. Most of the roofs are missing, and as our jet drops its black tires and aims for the runway at Las Americas International, we look straight into the islanders' concrete-block lives, their belongings violently mingled: plastic bags, rain-soaked clothes, walls impaled by corrugated tin. And in all directions are the triangular, tornado-shaped plumes of garbage fires.

What it lacks in glamour, maybe, Santo Domingo makes up for in history. This is the oldest capital in the New World. With some time to kill I hire a taxi, this time with no resistance. I'm going to see Christopher Columbus, who died in Spain but whose remains, depending which historian you believe, are interred beneath the cathedral here. To me there's something about that name, Santo Domingo, that evokes images of 16th century explorers, their gray-sailed ships anchored offshore. To others, maybe, it's thoughts of the slave trade, of indigenous Dominicans keeling over from those special European gifts of smallpox and typhus. Or boats taking cannonballs through their hulls, bars of gold falling to the ocean floor.

As with every big capital down here, from Havana, Cuba, to Panama City, the whiteness of the skyline is striking. White paint splashed over everything: hotels, apartment blocks, schools. From the highway it looms ahead, the city as a great white heap of anonymity, brutally conspicuous yet concealed. Clusters of white buildings set against brilliant blue beachfront; against emerald hillsides; against the mushrooming, oil-black storm clouds. And as the taxi brings me closer, I taste and feel that force of humanity and heat -- a grimy tropical ooze through every white crack.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Do you have questions for Salon's aviation expert? Contact Patrick Smith through his Web site and look for answers in a future column.

Shares