"Being black is a little like being a communist." I recently found myself making this odd comparison in order to encourage independent critical thinking in a black student of mine who had embarked on a term paper about Saartjie Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus, and perceptions of black women's bodies in Western culture. I was referring to the Soviet-style communism of the '70s and '80s, in which Russians perpetually scrutinized one another to ensure that everyone strictly adhered to party line -- at least in public. Of course, communists had a habit of purging traitors violently, whereas black Americans normally draw the line at denouncing them verbally, but I meant to invoke this principle in stark terms so that my student would understand.

I wanted to get across to her that black critical thinkers often face an extra step in the writing process -- we have to separate what we think from what our comrades of color expect us to believe, presume we believe, or would rather we didn't discuss in racially mixed company, in public, or at all. For us to reason independently of Negro orthodoxy -- especially to criticize sacred cows of black America like affirmative action -- means risking banishment from the black community. The threat of getting kicked out of blackness (impossible as that sounds), or at least being seen as outside black solidarity, looms large. Not even Harvard Law professor Randall Kennedy, who has touched the hem of revered civil rights champion and Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall's robe, has escaped the wagging finger of blame. He too has been called a sellout. More than once.

Kennedy was once feisty enough to have written a book about the N-word without fear of repercussion (for which he was called a deserter by fellow Harvard professor Martin Kilson, writing in the Black Commentator). In his new, compact examination of heresy in black culture, "Sellout: The Politics of Racial Betrayal," he's less bold, and he takes care to reassure readers of his position within acceptable black thought. In one of many long footnotes, Kennedy defends his use of the terms "Negro," "colored," "black," "African American," and "people of color" in the book: "I realize that vigorous political struggles have shaped the history of these terms and that today some of them ... are seen as either antiquated or insulting. In my view, words take their meaning from the context in which they are used."

In essence, he apologizes for varying the word he uses to describe his subject, a self-justification necessary in very few other writing situations. If he were writing about spoons and he wanted to call them utensils, he wouldn't need this qualification. But cutlery can't jump up and label you an Uncle Tom. Kennedy's defensive move will seem all too familiar to anyone whose audience is partly composed of touchy black folks ready to pounce. (I'm bracing for it right now. How dare you call us "touchy"!) For Kennedy, writing a treatise in which he defended the selective use of the word "nigger" might have been risky, but calling a book "Sellout" is a whole other level of peril: It means asking colored people to mistake it for a memoir, and to hide the cover if we dare read it on public transportation for fear of raised eyebrows.

Fortunately, it's no how-to manual. Kennedy's chapters are dense, stuffed with facts and anecdotes, compressed almost beyond belief. His second and third chapters move the reader through roughly 177 years of black sellout history in approximately 50 pages. Since this history has been suppressed almost by definition, it has the advantage of offering a fresh look at a rarely considered aspect of black history. I'm pretty sure that the slave commended by his masters for helping to thwart the 1739 Stono Rebellion, in part by killing rebellious fellow bondsmen, has never shown up on any of those black history calendars full of noble-looking portraits of heroes, even though he was named July. You can bet that the words of William Hannibal Thomas, the first black man to attend Otterbein College, have never been trotted out at graduations, sermons, or rallies. Thomas' 1901 screed, "The American Negro: What He Was, What He Is, and What He Will Become: A Critical and Practical Discussion," posits that "the negro represents an intrinsically inferior type of humanity, and one whose predominant characteristics evince an aptitude for a low order of living." Anyone who, like me, has a morbid fascination with deliberately forgotten corners of history and wrongheaded, outdated belief systems like W.H. Thomas' will wish that Kennedy had expanded these chapters, perhaps into their own jaw-dropping, crazy book.

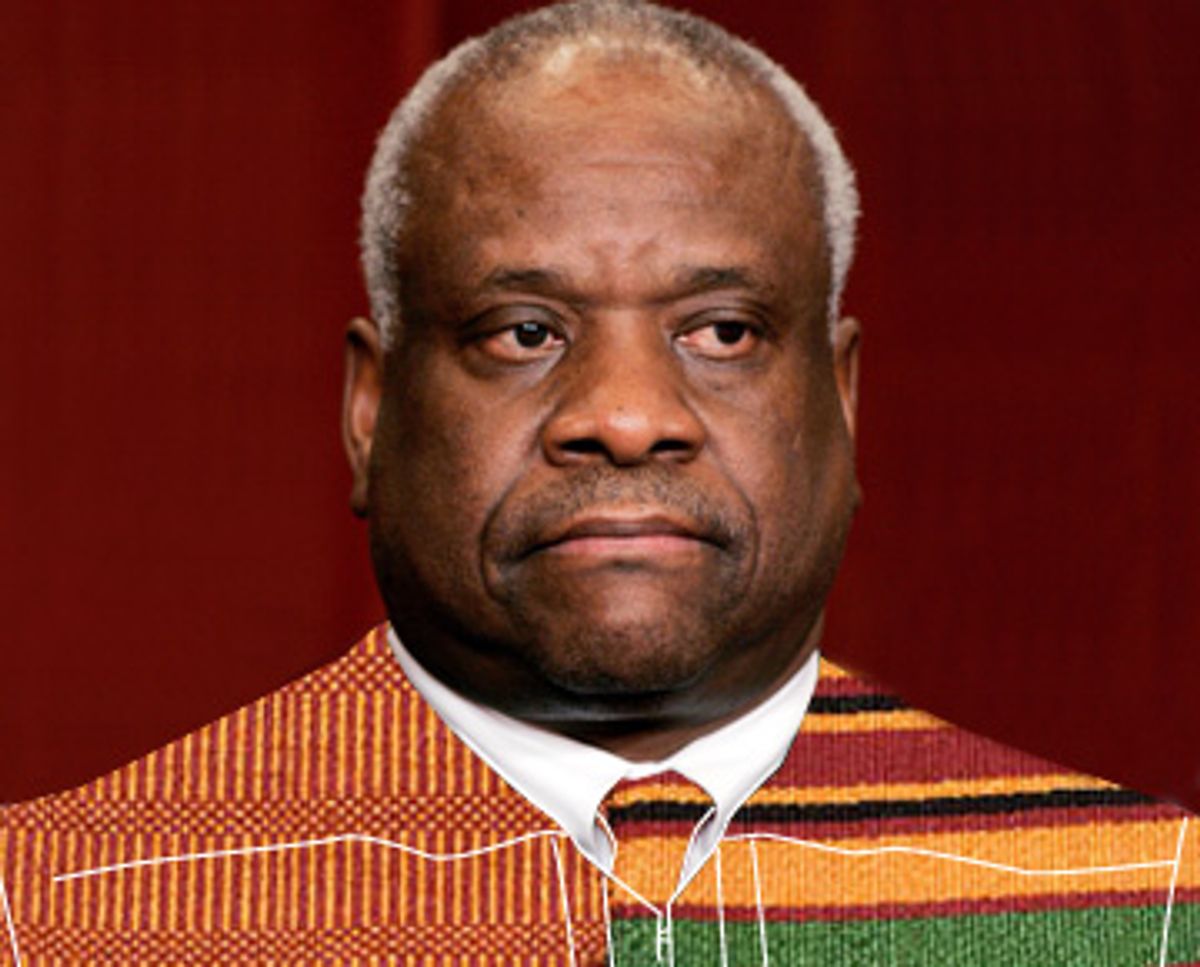

Instead, Kennedy devotes a lengthy chapter to a contemporary Thomas -- Supreme Court justice Clarence, that is -- whom the author describes as "the most vilified black official in the history of the United States." Rhetorically, Kennedy holds the cantankerous judge at arm's length and pinches his nose even as he defends Thomas' right to argue against the black Politburo and clarifies the negative position on affirmative action for which most blacks hate him. "For all his deficiencies ... Justice Thomas is a jurist with his own ideas," Kennedy concedes. "They are ideas with which I often disagree. But they are his ideas." For this former Rhodes scholar, it isn't just Thomas' denunciation of affirmative action as reverse racism -- "There is no sillier idea than this in all of American law," writes Kennedy -- that black folks resent, but that Thomas benefited from the program and then called for its abolition, essentially closing the door behind him.

On the issue of whether Thomas qualifies as a sellout, Kennedy is surprisingly generous:

Those who prosecute Thomas for racial betrayal assert that he is guilty of more than being wrong. They imply or assert that he deliberately harms Black America, or knows that he does so without a justification or excuse, or pursues a dangerous course of action without heed of consequences ... It is one thing to charge someone with hurting the cause of African Americans. It is another to charge someone with knowingly or willfully hurting the cause. It is the knowingness and willfulness that makes "selling out" so reprehensible.

By narrowing his definition of who qualifies as a betrayer of the race to extreme cases --for example, "an African American member of a black uplift organization who reveals its secrets to anti-black adversaries out of malevolence" -- Kennedy allows "Uncle Thomas Reptilious," as one reporter called the justice, to squeak under the gate.

As an elegant and open-minded exercise in argument, one has to admire Kennedy's defense -- judging by Kennedy's examples, nearly all of Thomas' critics eventually get around to calling for his death. Kennedy is right to advocate for more nuance in the definition of the party faithful and the race traitor -- he even makes a solid argument for those who exposed planned insurrections as a strategy to avoid violence -- but he couldn't have made it harder to swallow than requiring his audience to redeem Clarence Thomas in the process.

Even so, I agree with Kennedy that the sullen justice has the right to criticize affirmative action programs despite having used them to get a leg up. In fact, his firsthand experience might have had the potential to make him a better judge of its strengths and weaknesses. But Thomas, armed with that silly idea, wishes to abolish these programs wholesale, not modify or improve them. He may be responding to the blowback of insecurity that affirmative action kids sometimes suffer, the nagging suspicion that one can't truly compete without that leg up. Thomas may even be expressing that anxiety in his zeal to annihilate race-based institutional decision making. However, I've often suspected that Americans who wish to abolish affirmative action also find these programs embarrassing because they make certain uncomfortable truths about our country and white privilege visible. Within legal bounds, most U.S. citizens, regardless of color, find it perfectly acceptable to use whatever unfair advantage they have to get ahead --longtime friends on search committees, uncles with hiring ability, puffed-up résumés, glamorous Internet profile pictures. Mild corruption's fine as long as it remains hidden and doesn't interfere with the perception that our country is a meritocracy. Playing dirty is part of our national heritage; we began this country by all but evicting its Native American leaseholders. White people have affirmative action, too -- and predictably, it works a lot better than the black version.

Though Kennedy doesn't touch on this aspect of Thomas' opinions about affirmative action, "Sellout" does a great deal to complicate the politics of racial betrayal and opens up a space between dissent and disloyalty, where a critical consideration of that set of beliefs we think of as tenets of black American identity doesn't have to make anybody the next William O'Neal, paid by the FBI to deliberately disrupt the activities of the Chicago Black Panthers. Or even the next Charles "Rat Killer" Barnett, who informed on Alabama civil rights leaders to Birmingham police chief Bull Connor, a Ku Klux Klan member notorious for breaking up protests with fire hoses and attack dogs. (Somebody needs to make a calendar out of that rogues' gallery.) While Kennedy won't foment anything on the scale of black perestroika, "Sellout" does a provocative job of nudging us toward a little more glasnost.

Shares