Prior to the South Carolina Republican primary earlier this month, a group calling itself the Vietnam Veterans Against John McCain launched a dubious attack on McCain's behavior as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Led by an activist named Jerry Kiley, the group alleged, with little factual basis, and with no effect on the primary, which McCain won, that the Arizona senator had collaborated with the enemy when he was a prisoner, and that he had been turned into a "Manchurian Candidate" during his captivity.

Kiley, who once tried to throw red wine on Phan Van Khai, the then-prime minister of Vietnam, has a history of extremism. And his South Carolina leaflet was reflective of similar attacks on John McCain's war record over the years, launched by a minority of POW activists who believe American POWs may still be alive in Southeast Asia. At first glance, one might assume that Kiley et al. are the exceptions, and that the mainstream of the POW community -- former POWs, their families and the families of those missing-in-action (MIA) -- would hold John McCain in high regard. After all, the man spent five-and-a-half years in a Vietnamese prison and despite being the son of a Navy admiral refused offers of early release unless his fellow prisoners were set free as well.

But, ironically, even setting aside fringe characters like Kiley, McCain has an icy relationship with the POW/MIA community. One longtime activist who has known McCain for decades described "real antipathy" toward the senator among families of the MIAs. And activists say that is not because of any widespread belief that POWs are still being held hostage. (Clydie Morgan, the national adjutant of American Ex-Prisoners of War, which released a statement condemning the anti-McCain leaflets, says that most members of her organization do not believe that any POWs are still alive in Southeast Asia.) On closer examination, the paradoxical story of McCain and the POW/MIA issue seems as complex as the American struggle with the legacy of the Vietnam War itself -- and fraught with the same raw emotion.

Some of the hard feelings were sparked by the senator's stance on relations with Vietnam after the war ended. They were exacerbated by his choice of allies in pushing that agenda forward. And even some levelheaded government officials worry that McCain's policy positions over the years have made it harder to determine the ultimate disposition of those Americans still unaccounted for in Southeast Asia.

McCain's first sin was being a very early proponent of normalizing relations with the government of Vietnam, or resuming official political and economic ties cut off after the conflict ended. McCain's efforts in this realm infuriated some veterans still stinging from the American experience there. "Some people just can't let go of their hate," explained Rick Weidman, director of government relations at Vietnam Veterans of America.

For example, as a congressman from Arizona in the early 1980s, McCain and Tom Ridge, then a congressman from western Pennsylvania, supported legislation that would have created a U.S. Interests Section in Vietnam, a low-grade version of an embassy and a signal of warming relations between the two nations. That touched a nerve for some veterans.

During this period, the Reagan administration had launched new and serious efforts to get information about Americans missing in Southeast Asia. But the Vietnamese held all the information -- access to crash sites, prison records, aircraft shoot-down reports. And the administration's strategy was to take incremental steps toward normalization, but only in return for serious cooperation from the Vietnamese on the disposition of unaccounted-for Americans. The concern was that people like McCain would give away the carrot. Among some veterans, McCain wasn't making any new friends. "'Enemies' is probably not the right word," remembered Richard Childress, a Vietnam veteran who as director of Asian affairs at the National Security Council during the Reagan administration worked on POW issues. "But some questioned his judgment because he tried to move so hard and so fast," he said. "Even informed people on the issue thought he was going too far."

Then during the administration of George H.W. Bush, McCain served on a Senate committee aimed at figuring out whether any American POWs might still be alive in Southeast Asia. The final report, issued in January 1993, concluded that "there is, at this time, no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia." It added that "the question arises as to whether it is fair to say that American POWs were knowingly abandoned in Southeast Asia after the war. The answer to that question is clearly no."

The findings infuriated the more conspiracy-minded elements in the POW/MIA community. The Jerry Kileys of the world think McCain has committed an unthinkable sin. "Some people believe that there are live POWs still from the Vietnam War," explained Morgan of American Ex-Prisoners of War. "And they felt like Senator McCain did not delve deeply enough into that, considering that he was a POW." But Morgan, while hastening to say that her organization considers McCain "one of our own," acknowledges that McCain's unpopularity extends beyond the fringe.

Fair or not, the senator has also generated a reputation as being hostile to the families of those Americans still missing. And some of that is probably his fault. A well-known example is his barbed exchange with a witness whose brother went missing in Vietnam. Dolores Apodaca Alfond, who appeared before the Senate committee on Nov. 11, 1992, expressed concern that the committee might shut down without finding all the answers. The famously testy McCain bristled at the suggestion. "I do not denigrate your efforts," he said. "And I am sick and tired of you denigrating mine and many other people who have views different from you." Even he admitted that day that he may have "appeared upset." News clips say McCain left the hearing room that day to the sound of hisses from the audience of around 50 relatives of missing Americans.

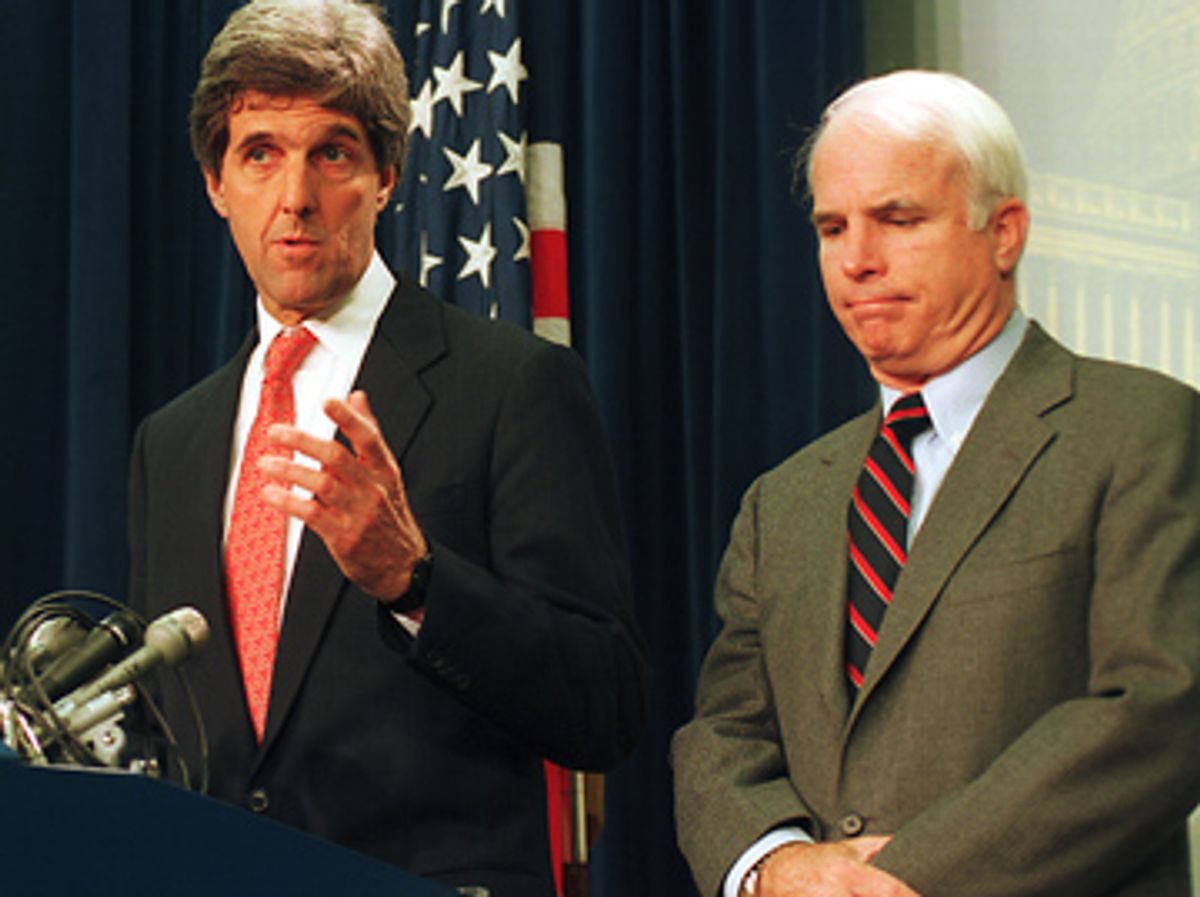

That panel was chaired by Massachusetts Democrat Sen. John Kerry, a Vietnam veteran who already had a troubled relationship with his fellow veterans because of his outspoken opposition to the war after his tours of duty. It was while serving on the panel together that McCain and Kerry solidified a friendship. In addition to their experience in Vietnam, the two men shared the belief that the United States would be more likely to get information about Americans unaccounted for after the war by normalizing relations with Vietnam.

In the spring of 1993, the two men traveled to Vietnam together. On their return, Kerry reported "very special efforts" by the Vietnamese to help the United States get more information on missing Americans. But some experts in the field didn't see any substantive progress by the Vietnamese. "[McCain and Kerry] were coming back [from Vietnam] and making pronouncements of great progress," said Childress, the Reagan administration official. "And those of us who dealt with the Vietnamese for many years know progress when we see it."

Normalization of relations with Vietnam went into high gear during the Clinton administration, with the full support of McCain, a process that is now complete. But many observers believe that President Clinton -- who did not serve in Vietnam -- could not have moved aggressively to normalize relations without the political cover provided by McCain, the war hero. Among the POW/MIA community and some veterans, McCain is referred to as a "cardboard cutout" for Clinton during this period on this issue. It did not further endear the Arizona senator to some veterans.

All these things accumulated over time. "A lot of people thought he moved too fast and too far with normalization, probably in good faith," Childress explained. "And then when he joined with Clinton, he identified himself with that. And when he and Kerry became good friends, and with everything he had said about Vietnam veterans, all that added up in people's minds." Kiley's campaign against McCain is, in a sense, just a continuation of his work against McCain's Senate colleague during the last presidential election. He and Ted Sampley, organizers of Vietnam Veterans Against John McCain, also formed Vietnam Veterans Against John Kerry and worked to discredit Kerry's record in 2004.

Unfortunately, it is possible that the normalization route favored by McCain and Kerry did come at a cost to some of the families of missing Americans. There are still 1,763 Americans missing and unaccounted for from the Vietnam conflict. Based on U.S. government information, the National League of Families, an advocacy group for the families of those Americans, estimates that with full cooperation from the Vietnamese, remains or proof of death could likely be ascertained for half of that number. The United States has formally asked the government in Vietnam for a raft of specific documents -- like results of Vietnamese crash site investigations -- that might shed some light on these. The documents have not been forthcoming. Some experts think this is because there is little upside for the Vietnamese to go out of their way now.

Shares