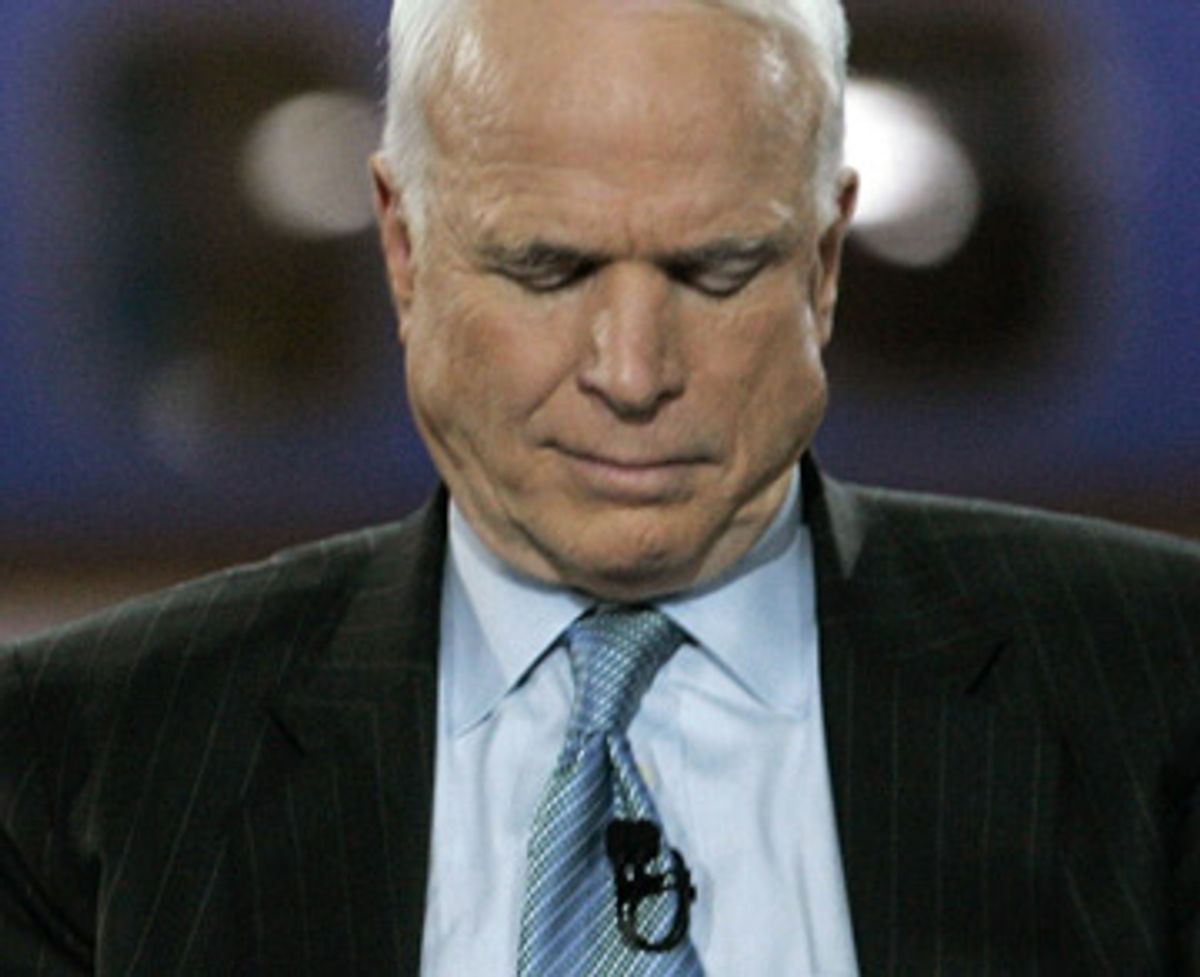

Should John McCain emerge victorious from the Super Tuesday primaries next week, as now seems likely, his remarkable revival will impose a stark test on the national press corps. It is a test that the press has failed in years past, and that has only become more critical as the Arizona senator moves closer to his party's presidential nomination.

Given the unabashed affection that so many in the mainstream media display toward McCain, will he be covered fairly and without favoritism? Will he be subjected to the same sarcasm, gossip and investigative zeal so routinely applied to, for example, his potential Democratic rival Hillary Clinton? Will McCain's panders, flip-flops, gaffes and fumbles receive the kind of attention that embarrasses other politicians? Or will he remain exempt from the unsentimental scrutiny that is supposedly the standard of our political journalism?

Hey, almost everybody seems to know the answers already! But for a few minutes let's pretend we don't.

The problem that now confronts the journalists who have lavished so much love on McCain is whether to let America in on a sad secret about the straight-talking maverick, which is that he has transformed himself into a fairly typical politician. After years of tending the McCain mythos, its builders must either continue to maintain it or tear it down.

Like most appealing political myths, his includes more than a little truth. He's still that salty, wisecracking, accessible, irrepressible pol, surely among the most likable characters in Washington (as long as you don't get on his bad side). For better or worse he still says what's on his mind, unedited (at least sometimes).

But McCain's performance in the California debate proved again that he has abandoned the principled positions admired by so many independents and even Democrats, though not always by Republicans and conservatives. Where was the straight talker when Janet Hook of the Los Angeles Times asked whether he would vote for his own McCain-Kennedy immigration reform bill if it came to the Senate floor tomorrow? That guy would not have avoided the question, as McCain did, peevishly retorting that the cursed bill will never come up for a vote. But then that guy left the building many, many months ago.

McCain used the same evasive tactic when Hook asked him about the Bush tax cuts, which he opposed on principle in 2001 and which he currently seems to support retroactively. She pointed out that he originally criticized those cuts as biased toward the superrich, an argument we would expect to hear from a Republican rebel bucking the party establishment and the big boys. But now he meekly claims that he worried about offsetting that fat-cat feast by taking enough away from everybody else in budget cuts. He changed the subject to his political youth as a "foot soldier" in the "Reagan revolution" two decades earlier.

Those little episodes got scant attention in coverage of the debate, while most stories focused on the silly semantic spat between McCain and Mitt Romney over the Iraq escalation. "'Timetables' was the buzzword," McCain kept muttering, perhaps incomprehensibly to most viewers. But as the former maverick keeps shedding the moderate positions that dismay the Republican base, he is hollowing out the persona that launched a thousand adoring profiles. He dropped his opposition to the religious right years ago, and has since walked away from the campaign finance reform crusade that once defined him.

Speaking of reform, just how much of a reformer is McCain? The myth as recounted by the maverick himself and his admiring scribes is that the searing experience of the Keating Five scandal purified his character. Never again would he allow himself to be turned away from the path of righteousness by lobbyists and donors, never again would he sell out the public interest to the high rollers, never again would he besmirch the honor of his office ... and so on.

This is inspiring stuff, and he may well believe it all, but there is a growing backlog of evidence that he has not always lived up to such exacting standards -- particularly during his tenure as chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee.

Consider just one McCain story that never drew the roaring gang of cable and print hacks who would surely show up if someone named Clinton (or Edwards or even perhaps Obama) had done the same thing. It is the story of an entity that the Arizona senator founded, known as the Reform Institute.

Created after his failed presidential run in 2000, the Reform Institute is a hybrid between a domestic issues think tank and a tasty sugar teat for campaign staffers. Among its senior fellows is former Mexican Cabinet member Juan Hernandez, who also heads the McCain campaign's outreach to Hispanic voters. Other Reform Institute employees have included lobbyist and political consultant Rick Davis, long a member of the McCain inner circle and now his campaign manager.

The sweetest aspect of the Reform Institute -- aside from its commitment to research on immigration reform, campaign finance and other liberal concerns that the senator no longer finds so relevant -- is that its own financing is not subject to the regulations and disclosures of federal election law. In practice, that has meant not only that the McCain crowd could sop up subsidies from foundations run by liberal Democrats but that corporate donors with issues before the Commerce Committee could chip in a few bucks, too. Or a few thousand bucks, or even 50,000 bucks or more, like the executives of Cablevision (under the name CSC Holdings) and Echostar, communications firms with substantial issues at stake before McCain's committee.

Then there was that contribution from American International Group, whose executives had been quite concerned in 2000 about McCain's vow to stop AIG from profiting illicitly on insurance overcharges ripped off from the Boston "Big Dig" project. Sen. John Kerry got most of the blame for the demise of McCain's reform bill, which would have banned insurance giants like AIG from overcharging federal projects and reaping windfalls from investing that money. But it was actually McCain who killed his own bill -- and nobody seems to have checked back to discover that AIG later donated more than $50,000 to the Reform Institute. How much more? That might be a relevant question now, notably because Maurice "Hank" Greenberg, the McCain backer who ran AIG in those days, has since been forced to relinquish the company under threat of criminal prosecution.

These are precisely the kind of questions now aimed elsewhere -- at former President Bill Clinton's foundation, to take one prominent and appropriate example. The national press corps may never direct such skepticism toward their pal McCain, but it takes true willpower to resist reporting on a soft-money operation called the Reform Institute.

Shares