While the rest of the country awaits the outcome of Super Tuesday, New Orleans is celebrating Mardi Gras. This is typical for a city that has often, stubbornly and even to its detriment, done things its own way. New Orleans is a singular town, one of the reasons that people from cities with less sensuality and weirdness have felt such a strong tug toward it over the years. Even one of its most famous personalities, chef Emeril Lagasse, was born and raised in Massachusetts.

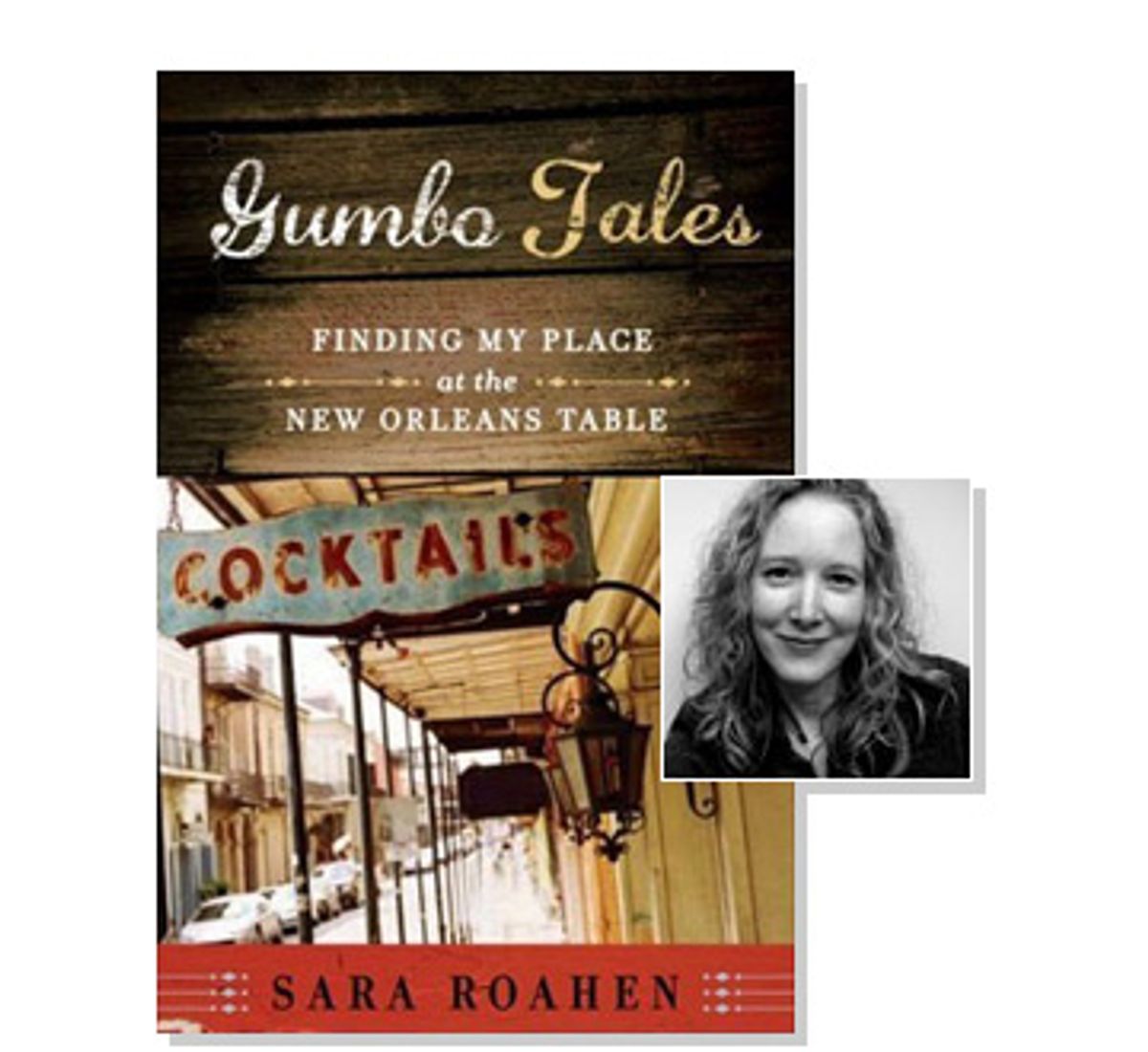

Author Sara Roahen is an adopted New Orleanian, too. The former Gambit Weekly food columnist practically grew up in another country -- though you could also call it Wisconsin -- and moved to New Orleans when her then-boyfriend, now-husband became a medical student at Tulane. A lightweight drinker and former vegetarian who'd logged time in the health-conscious kitchens of Northern California, she wasn't the most obvious fit for the Big Easy; nonetheless, she fell in love. "Gumbo Tales: Finding My Place at the New Orleans Table" is an endearing collection of stories from the seven years she spent in the Crescent City, learning to embrace its unapologetically decadent cuisine. It is part culinary history, part memoir and part homage to places that have since been erased.

It's been a painful recovery for New Orleans, though recently, on the WWL radio program "The Food Show," host Tom Fitzmorris offered the encouraging news that New Orleans now has more restaurants than it did pre-Katrina. So many things were lost during the storm, but so many endured, things that Roahen writes about with the curious eye of an affectionate outsider: Hansen's Sno-Bliz on a swampy summer afternoon; the grumpy butchers at Central Grocery; the barbecue shrimp po-boy at Liuzza's by the Tracks; the black-tie debauchery of Galatoire's; cocktails, oysters, crawfish, gumbo.

Let's start out by talking about gumbo. Can you talk about some of the possible origins of gumbo in New Orleans?

There are a few theories. First of all, "gumbo" is an African word (quingumbo). I was just at a writers conference in New York, and I met a woman from Liberia who told me that gumbo in New Orleans tastes just like the dish called gumbo in Liberia. The word "gumbo" means okra in one of the Bantu languages, according to food historian Jessica Harris, and okra is the main ingredient in some gumbos. So, many food historians believe it originated in Africa. There are a lot of sources that also posit that it was inspired by French bouillabaisse, "fish soup." That seems logical, but it doesn't seem to be true.

The problem is that gumbo is such a huge topic. When I wrote the chapter on gumbo, I worked on it for the better part of three years. And at that point, I thought, I'm no expert, but that's everything I know. Then, last summer, I did 20 oral histories about gumbo, and I realized I know nothing. I met people who put Spam in their gumbo. I met people who make squirrel gumbo.

So what's your favorite bowl of gumbo?

My favorite is what I call "Big Mama Style" gumbo, after the first one I tried [Big Mama's Gumbo at the now-closed Inn Restaurant]. That's a style of gumbo that has a lot of ingredients -- it's very chunky, there are pieces of crab with the exoskeleton still on and it's a thin broth. But I think it became my favorite because I loved the places where I would find it. They were always these owner-operated, small places in the neighborhoods. Two Sisters Restaurant. Dunbar's Creole Cooking. Both of those places flooded, but they've reopened since, although Dunbar's didn't get to open in its original space. And there's a place called Stella's, which no longer exists. These are places where the clientele was mostly African-American, and it was fun to participate in something that was not my native culture, this regular Friday tradition of eating gumbo.

Why is gumbo eaten on Fridays?

Well, you can walk into a restaurant any day of the week and get gumbo, but this kind of gumbo is usually served on Fridays, in particular because it's expensive. And time-consuming. At some point, it probably had something to do with not eating meat on Fridays during Lent, although there's meat in it now, most of the time. But New Orleans is big on having certain special days for specific foods.

Like eating red beans and rice on Mondays. What's the story behind that?

There's a folk story that says when you were doing your laundry in big pots over a fire on Mondays, it would be an all-day affair, and it made sense to put on a long-cooking dish like beans beside it. And you would go from stirring your laundry to stirring your dish. Who knows if that's true.

But even now, on Mondays, it'll be on the menu at so many restaurants. You can walk through the neighborhoods and smell it. You can go into stores and see people putting Blue Runner beans in their carts.

Another New Orleans staple, crawfish, is a difficult seafood to love, I find. Can you talk about how you came around to it?

I went to my first few crawfish boils, and I just thought, how does anyone get full on this? First of all, I was intimidated to peel those things in front of natives. But also, I didn't realize you're supposed to linger over it for hours. It's a social event, and you get your beer, and you stand over a mound of crawfish and talk and get to know people and you wait for the boil master to bring the next pot and it took me a long time to appreciate it. It also took me a long time to appreciate the taste of crawfish because it's very subtle, and to understand that people are enjoying the crawfish and not just the seasoning.

I want to talk about Mardi Gras, because there's a perception of it as frat boy bacchanalia. I always figured it was something people who lived in New Orleans hated.

Well, there are a lot of natives who do leave the city, because the celebration is not only on Fat Tuesday but for weeks before. On the other hand, the most hardcore Mardi Gras revelers are New Orleanians. It's the holiday of the year. There is that element of frat boy partying, but it's also such an amazing time of year to be with family and friends and have fun. New Orleans, in general, taught me how to have fun. It taught me to loosen up.

It's a very Catholic town, but there's not a lot of guilt.

It's a weird combination. One theory is that the Eastern seaboard was settled by the English, primarily, while the French had more of an influence on Louisianians, and the French have always had more of a free spirit. But I also think maybe climate has to do with it. You cannot remain buttoned up for most of the year. You have to let it all hang out, physically. Maybe that extends to the mentality as well.

And the lack of guilt extends to food. This is not a calorie-conscious town. At one point, you wrote about deep-fried oysters covered with brie, and I wrote a note in the margins that just said, "Whoa."

It's ridiculous. It can be a parody of itself. Food inventions in New Orleans can take on a comical air, trying to one-up the already excessive amounts of fat and flavor. I think the turducken [Paul Prudhomme's Thanksgiving creation that combines turkey, duck and chicken] is like that. But there are really refined Creole dishes and food preparations that aren't so over-the-top, that still contain a lot of flavor.

What do you find to be the hardest thing to explain to outsiders about New Orleans food?

Probably that New Orleans food isn't Cajun food. Once you try to tell them that, their eyes glaze over. Visitors always want to eat jambalaya and blackened redfish and the food they associate with Cajun food, and those things are actually kind of hard to find. I don't have an answer about where to eat jambalaya. I'm sure it exists in lots of tourism-driven restaurants. It's definitely something that New Orleanians eat, but it's a home-based dish. That's what a lot of people will eat on the parade route on Mardi Gras. But if you really want to eat Cajun food, go to Cajun country. Go to Acadiana.

You mention in the book one of the reasons people associate New Orleans so strongly with Cajun food is the prominence of chef Paul Prudhomme in the 1980s.

I think so. Also Emeril. Because he was the next big celebrity chef, and he's associated with that word. I don't think that's his fault. He never says his food is Cajun. Paul Prudhomme is Cajun, and grew up in Acadiana, although he is a really innovative, creative cook who mixed all these influences and created his own cuisine. He rides the Cajun wave, because it's bigger than he is. He's happy to explain that his cooking isn't 100 percent Cajun.

How is the city's food culture different from places like San Francisco or New York?

There isn't as diverse a variety of choices when you eat out. There's Thai food, but there isn't a huge range of Thai. What New Orleans does have is a lot of commmonalities. Everybody can eat and talk about gumbo. Food is a huge conversation.

You also mention that, unlike other food towns, there isn't as much excitement about the next thing, the hot new restaurant.

Right, that does not happen. There will be a spark of curiosity but also skepticism. It's like, well, we might just wanna go to Mandina's and get red beans, because it's Monday, and we love the red beans there. We'll wait and see about this new place.

There's a great New Orleans chef, Donald Link, who's opened two restaurants, Herbsaint and Cochon, that really clicked. And they are hot spots, but that's because he knows how to cook for the people, really knows what New Orleanians want to eat. Yes, he was a hot young chef who opened two comfortable, pretty designer restaurants, but that was secondary. I love that. Because I wasn't interested in new things, either. I wanted to eat what New Orleanians have been eating for centuries. There are thousands of kinds of gumbos, and I wanted to eat all of them.

At one point you call New Orleans "an ideal city for underachievers." One of the good ways to look at that is that people are willing, in the sense of European towns, to sit down and really enjoy a meal.

That is really true, even among the people I know there who are really busy. It's not like New York or San Francisco where, in terms of entertainment, you have a bazillion choices. I think that's kind of fortunate.

I haven't lived there in a little over a year, so I can't really speak to how the city has changed, and I'm not sure we'll know the real effects of Katrina for some time. But when I lived there I had a really extensive group of friends who were freelancers, living on a little but having a rich life. And almost none of them are doing that there now. It has become more difficult to scrape by. Our utility bills doubled. Our insurance and our property taxes doubled. It might still seem easy if you're coming from New York or San Francisco, but for people who were living that existence before the storm, it became cost-prohibitive.

Something I find charming, and baffling, is how the city keeps its own names for things -- snoballs instead of snow cones, po-boys rather than sandwiches. There's a willful differentiating from the rest of the world. And the city has its own vernacular. Instead of buying groceries you "make groceries."

Right. I loved the challenge of trying to be a local. It probably took me three years to say "po-boy" and not feel like a poser. It was something to live up to. The city is very localized, which brings me back to Mardi Gras, and you can't underestimate the power of a holiday during which every person in the city is out in the streets, dancing together, having the best day of the entire year together.

Shares