At a recent medical conference, I eavesdropped on a couple of doctors talking to each other about retail health clinics, small offices or kiosks that offer basic medical care in venues ranging from Target to Piggly Wiggly. These particular docs were not happy. One said some of his "easy business," patients who needed only a few minutes to handle, such as those with sore throats or colds, had migrated to the clinics. The other seemed perplexed that some of the parents in his pediatric practice seemed just fine paying cash to clinics, rather than coming to see him, where they had only a low co-pay.

These views don't surprise me. Doctors are naturally nervous about the rapid growth of retail clinics. About a dozen companies have opened some 400 shops with slogans that range from catchy, such as "You're sick, we're quick" (MinuteClinic), to direct, such as "We Make Quality Care Affordable and Convenient" (QuickHealth). According to industry experts, the number of clinics is expected to grow to over 700 this year. Wal-Mart began dabbling in retail health in 2005, when it opened 76 clinics. It says that over the next three to five years, that number could expand to 2,000.

Many medical groups, like the American Academy of Family Practice and the American Academy of Pediatrics (to which I belong), have published position papers opposing retail clinics. Their basic argument is that retail clinics run counter to the concept of "a medical home," a place where patients receive care for any and all of their problems. They worry that patients will have no sensible place to follow up their test results, and that putting a clinic in a mall or a Wal-Mart could expose shoppers to people with a contagious illness.

The medical community needs a second opinion. Retail clinics are good for American healthcare. By giving doctors a run for their money, they force us to do something we don't do well: innovate. At their best, retail clinics can make doctors look like smart entrepreneurs instead of a self-interest group futilely trying to protect archaic ways of doing business.

To understand why that's the case, look at the business-as-usual model of medicine. Anybody who wants to run a competent medical practice -- from the country doctor to the tertiary care hospital -- must measure success in terms of access, quality and cost. It's safe to say traditional medical practice is struggling to succeed here. Access is unpredictable for almost any practice. Most of us simply don't have the ability to provide round-the-clock care, short of the mediocre phone service of an on-call doctor or the chaotic, overcrowded emergency room. Costs keep rising and being shifted to consumers in the form of higher premiums, deductibles and co-pays.

Despite having the brightest medical minds and therapies, basic medical quality in America remains poor. According to a 2004 report by the Government Accountability Office about Medicare preventive services, 30 percent of people over age 65 did not receive a flu vaccine and 37 percent had never had a pneumonia vaccine. Another example: In 2000, Medicare estimated that 6.6 million beneficiaries were never told by their doctor that they had high blood pressure.

On the other hand, retail clinics are thriving. They provide excellent access. After all, what's more convenient than showing up any day, night or weekend to have your sore throat checked? No telephone time spent on hold trying to make an appointment, no shuffling your personal schedule to get there.

Then there's cost. Retail clinics operate on a fee-for-service basis and don't accept insurance. Most charge a maximum of $50, which is significantly cheaper than the $100-plus your insurance company (or you, if you carry an increasingly popular high-deductible insurance plan) will pay when see your doctor for the same concern. That relative savings makes retail clinics a great place to go if you're uninsured and have a minor medical problem.

This desire to pay out of pocket is a not-so-subtle sign that consumers are asserting their purchasing power in the health sector, just as they would with other goods and services. A 2005 Wall Street Journal/Harris poll confirms this: Eighty percent of retail clinic users expressed satisfaction with the cost of services; 89 percent were satisfied with the quality of care; 88 percent, with the staff's qualifications (usually nurse practitioners).

The success is due to a few reasons. First, retail clinics don't do everything. Literally, a customer has to choose what he or she wants from a menu of choices posted on a marquee. Choices are limited to simple, easy-to-handle medical problems like sore throats, allergies and cold sores or a request for routine flu or pneumonia vaccinations. No acute medical problems, like injuries or asthma, are addressed. All decisions are made using very strict decision trees, leaving no room to treat issues beyond or outside of them.

Clinics make no claim to be a medical home. Statistics support the safety of this approach. The CEO of MinuteClinic, the largest of the retail clinic chains, said in 2007 that they have never had a patient show up with chest pain, and that fewer than 10 percent of patients are turned away. Also, there's nothing complicated about communicating with a patient's primary doctor. Specialists and emergency rooms routinely send letters or faxes to primary care offices to inform them about a patient, his or her diagnosis, prescribed treatments and a follow-up plan. Retail clinics have made efforts to do the same. So rather than writing position papers opposing retail clinics, medical organizations ought to use them to encourage bold innovation.

But while we're waiting for Godot, doctors are starting to move on their own. Open access to doctors -- allowing patients to make appointments the same day -- have been implemented by centers like the Mayo Clinic, Kaiser Permanente and even some solo practitioners.

Technology is also helping. An increasing number of offices are adopting an electronic medical record, one that allows patients to e-mail their doctor or chat live over video. A recent study in the journal Pediatrics looked at 121 families who used e-mail to contact their doctor. Eighty percent of those surveyed either strongly agreed or agreed that e-mail improved the quality of communication with their child's doctor. Nearly 90 percent either strongly agreed or agreed that e-mail improved access to their child's doctor. I've use e-mail in my practice and have communicated with patients whether they're at home, at work or halfway around the world, to both my own and my patients' satisfaction.

Perhaps the best example of innovation comes from one Minnesota pediatric practice. It opened a retail-like clinic in its own office, offering walk-in appointments and expanded hours, including weekends and evenings. That's likely going to be a winner for two simple reasons: 1) The practice keeps its own clientele; 2) it makes access convenient for minor problems.

Most important, by relegating minor complaints to the walk-in clinic, a doctor can be a doctor. Many of us didn't get into this job to become "diaper-rash doctors," the kind who pack their day seeing patients with minor complaints to pay the bills. Yet after years of training and preparation, too many of us become just that. We simultaneously complain that we don't have the time to address the challenges that come with complex, chronic health issues, like obesity or childhood asthma. Adopting the retail model in-house could change the way we spend our time, allowing us to get back to practicing challenging and more satisfying medicine.

Of course, there are potential pitfalls. Should walk-in clinics expand to become a medical home by offering physical exams and other comprehensive services like treating injuries, they stand to do patients a disservice. Eventually, we will hear of a patient who had a bad outcome as a result of being misdiagnosed or mistreated. Time will tell whether the rate of errors is any different than in standard practice, but as long as the clinics continue to keep services strictly limited, this risk will remain relatively low.

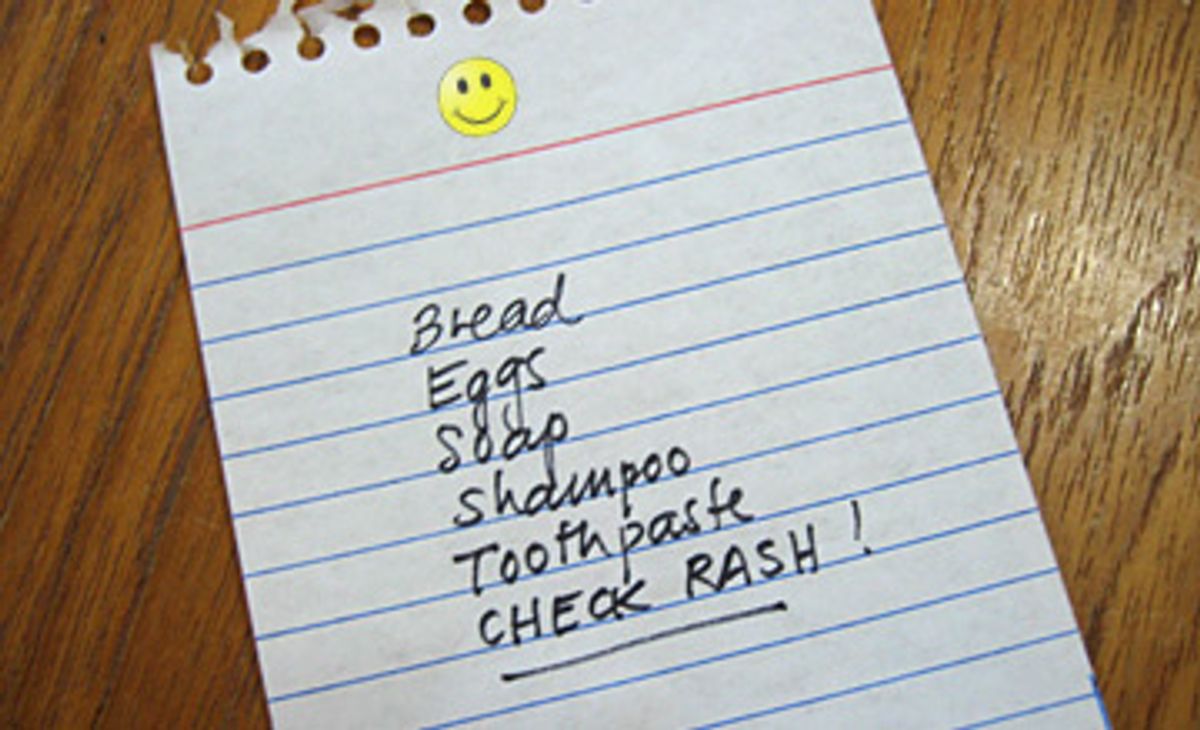

Regardless of those red flags, retail clinics in their current iteration have found a unique and useful niche in medicine. So the next time you make a list of things to do when you go shopping, you may be writing "check rash" or "get flu shot" under "buy shampoo and underwear." And you'll be just fine with it.

Shares