What is it about Barack Obama's baritone?

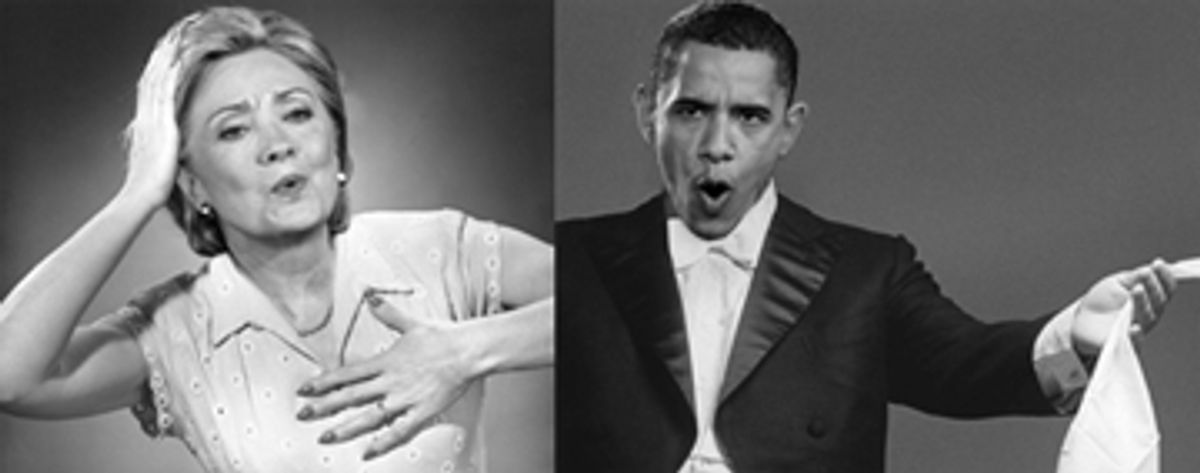

Aside from the symbolism of finding a new hero who might displace the shame and fear that has poisoned American public life since Martin Luther King's murder in 1968, there is something in the very essence of Obama's voice -- its tone, its timbre, its resonance -- that has struck deep chords among Americans and foreigners in this year's campaign season. Not since King's "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963 has a black American moved so many other Americans, white or black. And once the matter of voice was raised for Obama, a not always flattering parallel immediately arose concerning the voice of the first real female candidate in U.S. history: Hillary Clinton.

Eager to probe deeper into the chords of the candidates, I called two of the world's specialists on what moves us as listeners to others' voices, Lotfi Mansouri and Rick Harrell, who have coached singers at the San Francisco Opera and the San Francisco Conservatory opera program.

Says Lotfi, "The fact is that the basic timbre is a god-given sound. Through technique and vocal study and all that, you can learn to control it and develop it, but you cannot manufacture timbre artificially." Adds Rick Harrell, "The old saying is the eye is the window of the soul. Well I would say the voice is the window into the heart. People, whether they be actors or politicians, can be slick and manipulative and pretend to be genuine or heartfelt. However, the sound of the voice or the sound of a baby's cry or the sound of someone saying, 'Please! I can do what's best for our country.' It comes across at a very gut level more so than at an intellectual level."

When it happens that something within us shivers or tingles at the words of a great and moving voice -- Martin Luther King Jr. for my generation, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt for my parents, or even perhaps for some others Benito Mussolini -- it is because there is something that leaps forth from the very anatomy of the speaker, revealing the innate grain that vibrates with a receptive grain of our own. It is not about goodness or morality or truth-telling and is little affected by coaching or practice.

The late French semiotician Roland Barthes touched on this vocal magic in a famous essay called "The Grain of the Voice." He cites the power of a Russian church cantor's chant: "something ... is directly in the cantor's body, brought to your ears in one and the same movement from deep down in the cavities, the muscles, the membranes, the cartilages ... as though a single skin lined the inner flesh of the performer and the music he sings." Barthes goes on: "The 'grain' is ... the materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue." Like the variable grain of an oak or a walnut, it reveals, if we let ourselves hear it, the integral character of the person before us.

Mansouri and Harrell also wanted to talk about another iconic American voice -- that of Frank Sinatra. By no account did Sinatra possess a great singing voice. To the contrary, it was by most musical assessments decidedly mediocre. And yet, when Sinatra sang, it was as though he filled all the inner and outer dimensions of our experience. "Take 'One for My Baby,'" Lotfi said to illustrate. "He didn't just sing the words; you got the whole atmosphere inside and around the words and you were enveloped by it." Like the great Ella Fitzgerald, whom he studied, Sinatra employed all the technique he could muster: tone, phrasing, inflection, the single note prolonged beyond endurance. Yet all of that would have been as nothing had the story he was telling in his songs not also been the elemental, physical story of his own life. The mediocrity of his lightweight baritone disappeared and we became travelers on the pulsars generated by the anatomy of his voice box in a separate universe of his making.

Can we say that Barack Obama achieves something similar when he speaks his chant for change? That is apparently what is happening for tens of millions of Americans, not to mention the cheering galleries across Europe and around the world who want it to be so.

But set against that resonant Obama grain there is what appears to be a counter-grain of what is all too often labeled Hillary the Shrill, including all the gendered codes buried beneath the word "shrill."

Natasha Williams, a longtime friend from Ukraine, who directs the Balagula Theatre in Lexington, Ky., says simply that it is jarring to hear a lineup of self-important, deeper-voiced males followed by a higher-pitched female. We are conditioned, she says, to look for authority in the male voice -- even though she finds the Republican heir-apparent John McCain squeaky and the now withdrawn John Edwards tweaky. Hillary's problem arises, Natasha says, "when she gets excited and it comes across as angry and that upsets voters more than if she were an angry man. It's connected to the fact that when the mother is upset in a house, kids feel insecure. It's not like that with the father because the mother stands in between the kids and the father. But when mother loses it, then it's really scary because the whole sense of security goes tumbling down."

That's one interpretation. Lynn Meyer, who's done everything from political consulting to selling Florida real estate to writing a detective novel, has a different take on how men hear women's voices. "There are two voices that don't seem very threatening [to men]. One is the little girl voice -- either Valley girl or Jackie Kennedy's little tiny whisper. The other is Lauren Bacall's [she lowers her own deep and gravelly] very sexy voice. Anything between these two, women have to be very careful they don't sound like what I call 'the voice of civilization.' That's the voice who told you to eat your spinach, take your elbows off the table, asked you where's your homework. It's a voice that sounds like a bit of mother, then schoolteacher, and finally nagging wife."

Sound like that and you're dead in the water. That is too often Hillary's problem when she gets excited, Lynn says. "Every time she changes her register, people use that awful, sexist word 'shrill' and that's really code for the voice of the scold."

I put that proposition to Rick Harrell, the San Francisco Opera coach, who agreed that shrill is death to any public performer: "We wouldn't want our hectoring mother speaking to us from the White House for the next four years." Harrell's Opera colleague Lotfi Mansouri broke in, "It's a preconception. A cultural preconception."

One of those apparent cultural preconceptions afoot in the current political fray is a rather odd preoccupation with the baritone quality of Barack Obama's voice, an insight pointed out by my radio colleague Brenda Wilson, a woman raised in Virginia who often speaks in grave stentorian stanzas. "Type in the phrase 'Obama's voice' on Google and see what you get," she advised one day.

I did so as I was listening on the transatlantic phone line. "OK," I said, still clueless. "There are a lot of listings."

"More than just a lot, Frankie-boy," she answered. "How many do you see?"

"Yeah, there are a lot. A whole lot. Sixty-some thousand. But what's that prove?" I persisted. "Everybody knows he's a great speaker."

"Yes," she said, the schoolmarm slipping into her instructions. "Now, type in 'Obama's baritone.' What do you see?"

"Whoa!" I answered. "Two hundred and sixty-nine thousand results!"

"Um-hm," she murmured.

I waited.

"That's all," she said. "Isn't it curious that the hot candidate gets to be described as a baritone? I mean, really, what's so good about baritones?" I took the question back to Rick Harrell.

"When you hear commercials, whether on the radio or voice-overs on television, when they're saying, 'Trust me, buy this,' or 'Trust me, go here, go there,' as often as not it is a baritone voice. If they want to get you excited and stimulated, then they'll go for a higher-pitched sound."

Probing further into the hidden presumptions and preconceptions of the baritone, I came back to an old reference from Freud's student Theodor Reik, who proposed that the true baritone is an evocation of the ancient shofar, the ram's horn that came from Abraham's sacrificial sheep but was also the instrument Moses used to call the wandering tribes together at Sinai to hear the thundering words of God. Retreaded into 20th century neo-Freudianism the shofar/baritone becomes the vocal embodiment of phallic authority.

Hear my horn, hear my authority. It's not a great leap to hear the multiple meanings of the horn.

Freudians, we know, can find something phallic in just about anything that speaks, breathes or moves. But such interpretations of the power of the baritone long antedate Freud or even the children of Abraham. Last summer Harvard anthropologist Coren Apicella took herself and some tape recorders to visit the Hazda people of Tanzania, who live pretty much as their ancestors did several millennia ago. Apicella wanted to know what voice had to do with seduction, fertility and reproduction. To get at the question she invited a clutch of Hazda men into her Land Rover and asked each one to say, "Ujambo," or "Hello," in Swahili. Then she played her recordings for a group of Hazda women and asked them to rate the voices.

Hands down, the women chose the baritone "Ujambos" over the higher-pitched ones. "Why there's this relationship we're not entirely sure yet. It could be that these men have greater access to mates. And so maybe these men that have deeper voices have higher levels of testosterone, maybe they're better hunters and they're able to bring more food home to their wives," Apicella told NPR reporter Sean Bowditch. As it happens, when Apicella reversed the gender recording, the Hazda men seemed to prefer women with higher voices.

When it comes to the public arena, however, baritone is still the winning vocal register -- as Obama's string of primary victories, even among blue-collar white men, would suggest. It all comes back to how the baritone "is the voice one tends to associate with authority," as opera coach Rick Harrell says, to get people to buy stuff or take certain medicines or, where candidates are concerned, to "trust ... [that they] know what's good for the country."

Shares