Sunday night, the last season of "The Wire" took its final bow. Instead of leaving these beloved (and sometimes loathed) characters suspended in time, "Sopranos"-style, the writers chose to wrap up loose ends, providing viewers with a far more satisfying and unambiguous ending than they might've expected.

But that didn't stop us from wondering where these characters would eventually land. Will anti-hero Jimmy McNulty be happy away from police work? Will the evil mastermind Marlo Stanfield get back into the game? Will slimy reporter Scott Templeton ever get his comeuppance for fabricating stories?

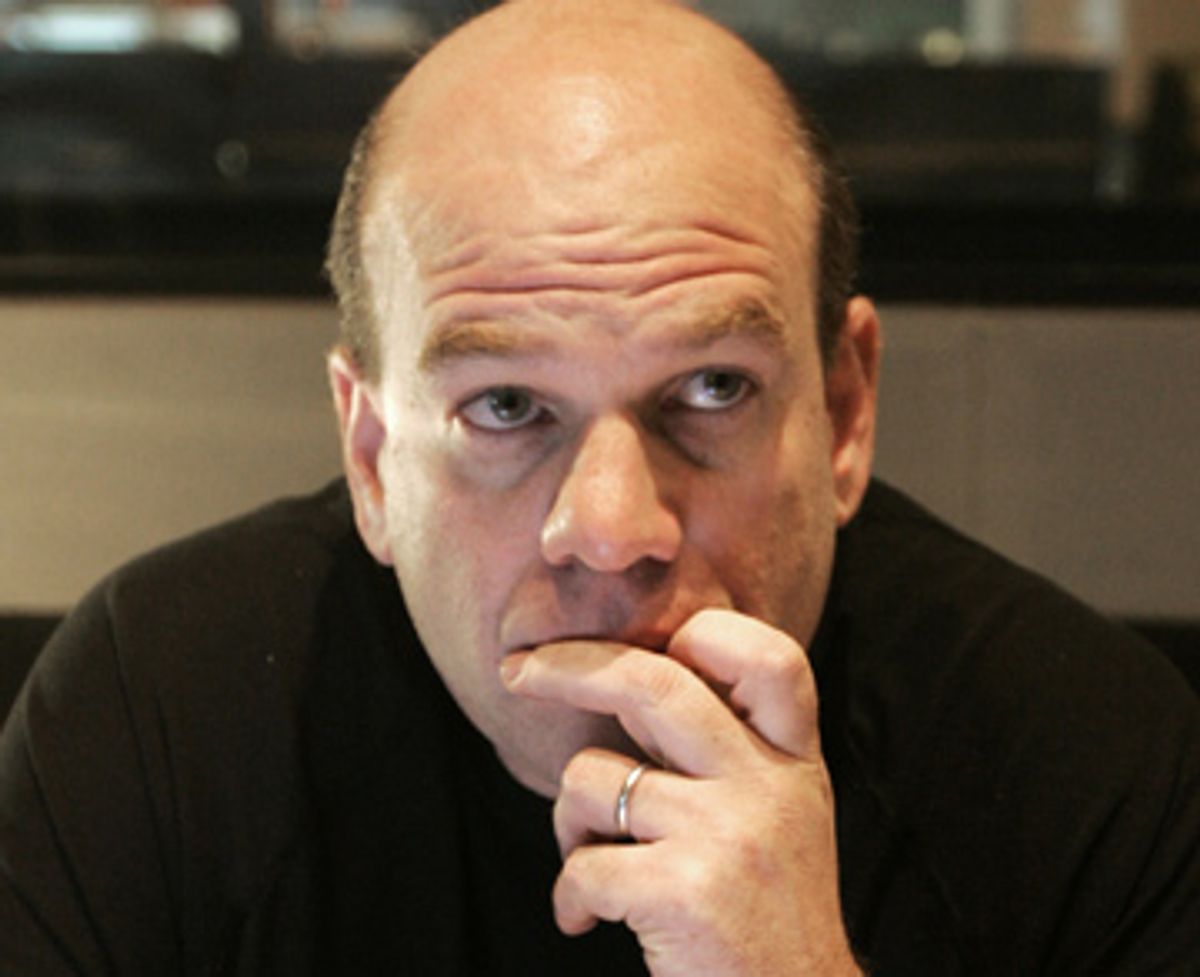

Not surprisingly, show creator David Simon was less interested in parsing the final episode for us than he was in discussing the overarching themes of his "postindustrial American tragedy." Phoning from Los Angeles, where he's finishing up sound work for his upcoming Iraq war miniseries for HBO, "Generation Kill," Simon preferred to discuss the larger implications of his creation, from the temptation that police face to bend the rules to the horrible odds facing kids who try to make it off the streets. Most of all, though, Simon delighted in the fact that, when it came to his depiction of the Baltimore Sun, his own old stomping grounds, many of his critics in the press missed the point entirely.

On the finale: I was amazed that McNulty and Freamon didn't end up in jail. But it was sort of a relief.

Really? You were happy for that?

Yes.

Some people were really angry at them this year. Especially McNulty.

Well, I guess I'm not very ethical, but I found it hard to root against them.

I think we were trying to be very ambivalent about it. I guess that was good if you struggled with it. Then we were doing something right, because we were trying to land it somewhere in the middle.

They definitely demonstrated what a slippery slope it can be when you start bending the rules. When they've done it before, it seemed laudable.

If you go back to the first season, there's a very telling moment that was sort of latent, which was when McNulty [was] doing the log book and Sydnor didn't see a key call that was part of their probable cause. And Prez says, "But Sydnor wasn't there." and McNulty says, "Yes, he was," and he writes it in the book. So that was always latent, the potential was always there, and it's always there for police officers.

Did you aim to find a situation that would leave viewers feeling conflicted?

And that would leave McNulty feeling conflicted. I think viewers can make their own assessment about whether or not McNulty is going to be happier in the police department or out. But I'm not so sure that this isn't the best thing that ever happened to him, in a merciful way.

Isn't police work his passion?

But it clearly drove him to the point of great turmoil and great ethical struggle. You know, he was happy being almost semi-retired, when he was walking foot in the Western, riding a radio car in the Western. That was a foreshadowing, I thought. At least it was intended as a foreshadowing. Maybe [he could] take a step away from this, you know? At least get out with [his] soul. And to a lesser extent for Freamon -- at least Freamon gets his pension.

But that's one reading of it. Other people might think that McNulty's never going to be able to survive without being a cop. We left that open. It's something to argue about. One of the great joys I've had doing this show is watching people argue over not just the characters but the ideas.

The other thing that [McNulty's fake serial killer] quite obviously did was, it allowed us to set up this juxtaposition between Templeton's ambition and McNulty's desire to bring the case in at all costs.

Some have said that they didn't find the serial killer storyline believable.

Is it impossible to stage a serial killer? No. One thing you won't hear is any pathologist who'll say, "Oh, there's no way that could fool us." That is the one way that postmortem injuries can be made to look antemortem: It's strangulation, bruising around the neck, and then suspend the body in a dependent position, make it so the head is in a dependent position.

[As a reporter] I saw something almost become a murder ... And afterwards I took a chief medical examiner to lunch to talk to him about it, just because it was interesting to me. He said, "Yep, that one can fool you." And I put it in my back pocket. That was almost 20 years ago.

Did you feel that those two characters could be led to extreme measures after years and years of finding ways around obstacles in the department?

Freamon had been told no for a long time, for most of his career. And McNulty? Shit, I think he'll try anything once. His intellectual vanity has been on display since the first season. But if people didn't believe it, they didn't believe it. I'm second-guessing people a little bit, and that's not fair -- every viewer's entitled to their own opinion. I think what they really didn't believe was that their favorite characters were behaving in an unethical way. That bothered them. I think TV shows are supposed to deliver on certain things. Omar is supposed to go down in a blaze of glory. McNulty is supposed to either lose and suffer or finally win, but he's not supposed to walk away from the rigged game and do something that bothers viewers.

Once you had the kids on the show last season, did you have trouble realizing that you were going to weave them into some pretty awful fates down the road?

No, we knew they were going there. Let me just say this: We're not being manipulative in any cynical way about marching those characters towards tragedy. If you read "The Corner" [the book Simon wrote with Ed Burns], of the kids that we followed, two are alive, two were shot to death as teenagers, and another is in prison. We looked at what happened to the kids that we followed when they were 14 or 15, and looked at what had happened to them by the time they were 17 or 18, and "The Wire's" story reflects the odds.

How hard was it to choose which kid would be saved, as Namond was by Colvin? It seemed like Randy was going to be the one who made it out.

The writers argued it out. That's the other thing, "The Wire" is not David Simon. I'm getting a lot of ink, but Ed Burns has a huge amount to do with this, and the other writers -- George Pelecanos and Richard Price and Dennis Lehane and Bill Zorzi. I mean it really is a team effort. And the stuff gets better when we sit around and argue with each other. We've been doing that for five years. We tried it in all variations, and we ended up where we ended up.

There's been some criticism of your depiction of the Baltimore Sun, with some claiming that you were too close to the material or had an ax to grind; one writer at Slate described a conversation he had with you about your feelings toward the Sun at a party. What has your reaction been?

At the beginning of the run I was very careful about not responding to any critiques of the actual show. We knew that we were going to take it on the chin from certain quarters in journalism, and we were fine with that. I mean, I put that line in the judge's mouth right in the middle of the run: "Never piss off people who buy ink by the barrelful." It's an old saw in journalism; you've heard it a million times. But I gave it to the judge at that moment because I thought, this is about the place in the run where the journalistic tantrum is going to sound like an alley full of cats. So it's all with a wink and nod and knowing that it's coming.

The fellow on Slate ... I went to a wedding with him, and we sat around at a table -- there was nobody but journalists at the table. We all talked about journalism, and I was asked a bunch of questions about what it was like to transition out of newspapers and why I thought I should do that and how it happened ... ultimately, I did write him privately and say, you know, I was a reporter for many years quoting dozens and dozens of people by name, some of them about very intimate moments in their lives, and not one of them ever didn't know that I was a working reporter. If you wanted to talk to me about [former Sun editor and managing editor] John Carroll or Bill Marimow or the Baltimore Sun or journalism or anything, all you do is pick up the phone. I'd take your call. I'm certainly not bashful about answering your questions. Why did you need to cannibalize my private life? Because if that's the case, I'm not coming to the wedding and I'm not coming to the party anymore. [Editor's note: Simon responded to the Slate piece here. Slate's David Plotz apologized here.]

How do you feel about being painted as this bitter person?

When all they've got is the ad hominem, then that's all they've got. I'll tell you a little something about [Mark Bowden, the author of the Atlantic's piece on Simon, "The Angriest Man in Television"]. He sent me an unedited version of his story and asked for comment. And my comment to him was, Listen, Mark, I don't care what you say about the show. I don't even care about you calling me angry ... But I do resent you basically declaring -- as he did in the piece that he sent me -- that by criticizing these guys [Carroll and Marimow] for tolerating a fabricator and defending a fabricator long after he'd been caught repeatedly, I have slandered two honorable worthies. You acknowledge that they've been your career-long friends in journalism ... this is really about your loyalty to old friendships.

And so, I then asked him, Given that Bill Marimow has recently hired you for a job, to be a columnist for the [Philadelphia] Inquirer, do you think there's an ethical problem here? And he didn't answer, and in a separate snail-mail letter, I posed the question to [Atlantic editor James Bennet]. I said, I don't care what you write about the show, but the only guy who's being slandered here is me. I never slandered or libeled anybody in hundreds of bylines and a couple of books, and now I'm going to come up to two editors and just claim they did something that they didn't do?

And he responded by saying, Well, I have complete faith in Mark Bowden. And then Bowden, upon finding out that I dared to pose this question to his editor, he took the fact that my response to him was off the record and decided to characterize it [in his Atlantic essay]. Have you ever heard that you can take somebody off the record if they ask your editor an ethical question? I've never heard that.

Listen, I hold those fellows [Carroll and Marimow] in low regard, I hold what they value in journalism in low regard, and they the same for me. I left the paper in '95 -- I said nothing, I never invoked their names publicly in five years. There was a fellow who was making it up, he had two stories retracted in total, and there were a lot of people in the newsroom who knew that he was cooking it. A very good reporter [at the Sun] went to talk to Marimow [about it] and nothing ever happened. It was the same dynamic that happens at every paper when people start complaining about a problem -- same thing that happens to the [New York] Times people when they complained about [Rick] Bragg and [Jayson] Blair, same thing that happened at USA Today when they started worrying about Jack Kelley's copy.

As people are more fearful than ever of losing their jobs, it seems like the problem would only get worse.

At the time that I was at the Sun, there were three guys who made stuff up and got caught. Only three that got caught, but there were three, and I was there for 12 years. And by the way, one of them was heartbreaking. It was a guy who made up a quote in an obit. It was a cry for help if nothing else. He was a good guy.

The day that I took the buyout and left, I told John Carroll, I said, everyone in your newsroom knows that this guy's got a problem. You've already retracted two stories. You had to apologize to the mayor of Baltimore for a story that wasn't true. You'd better look at it, John. You may win a Pulitzer; you may have to give it back.

And he said -- this is the line, I'll never forget it -- he said, "Well, 24 hires out of 25 is pretty damn good, don't you think?" And I said, "Yep. I agree." I shook hands with him. I gave the warning. It didn't cost me anything because I was getting out of journalism. Five years later, I'm in an editing suite in New York, I'm working on "The Corner" and [a Sun reporter] calls me and says, "He did it again."

[Editor's Note: Accounts of the controversy at the Sun can be read here and here.]

How do you make stuff up that the people in question are clearly going to dispute?

You ever seen somebody who, the lie just keeps getting bigger and bigger? You start out just cleaning up a quote. I think it starts small. But here's the thing -- at that moment, I'm out of journalism, I'm not beholden to anybody -- I called the publisher of the Baltimore Sun, and he didn't call me back. John [Carroll] called and said, "Well, you're biased, you're bitter, you're angry. It was his honest mistake." I said, "John, how can it be an honest mistake?" And John said to me, "Well, it's in his notepad." That's always the last refuge of every scoundrel in journalism. "I don't know what to tell you, sir, it's in my notepad." But when he said that, I said, "John, you've already had to retract two stories from this guy, and now this is three."

This is John Carroll. I know he's Mr. Pulitzer, I know he stood up like a hero at the Los Angeles Times when they were being threatened with cutbacks -- though, by the way, he didn't at the Baltimore Sun; he was one of many people who took a buyout. But when the chips were down in L.A., he did the right thing, and God bless him. But at that moment I said, "John, if I was the editor of a major metropolitan daily and I had to retract three stories by the same reporter, I would remember it until the day I fucking died."

I went to work at the Baltimore Sun when I was 21 years old. I don't have many temples, but I got one, and you guys are changing money in it.

Well, that makes you Jesus, though.

Oh, I don't mean that. That was a bad metaphor. Oops. I have a lot of complexes, but I don't have a Jesus complex. I'm too deep into shit.

Do you ever have times when you think, "Enough with this stuff. I can't handle stirring the pot anymore"? I mean, do you feel sure that you'll effect change through being outspoken about this stuff?

No, no. Have you been watching "The Wire"? [Laughs.] I'm not effecting change in the slightest. On the other hand, I feel as if I've been able to, in my journalism, in storytelling, in television, and in the way I conduct my life, I've been able to speak openly and aggressively about anything that mattered to me.

In my mind and in the mind of the writers, the season 5 story was about a lot of things. The über-theme, the real lesson to the story, has less to do with the fabricator or even with the editors tolerating sloppy journalism or being obsessed with prizes. It has to do with what isn't on the screen.

What do you mean by that?

[The season] begins with a very good act of adversarial journalism -- they catch a quid pro quo between a drug dealer and a council president -- which actually happened in Baltimore. Not necessarily the council president, but between a drug dealer and the city government. That whole thing with the strip club? That really happened in real life. It was news. The Baltimore Sun did catch that, it was good journalism, so I was honoring good journalism. It ends with an honorable piece of narrative journalism, about Bubbles. And the Baltimore Sun has, on occasion, done very good narrative journalism.

In between those bookends, which I thought were important, because in our minds we weren't writing a piece that was abusive to the Sun or any other newspaper ... the paper misses every story. They miss that the mayor wants to be governor, so ultimately the guy who was the reformer ends up telling people to cook the stats as bad as Royce ever did. Well, in Baltimore that happened. And they missed the fact that the third-grade test scores are cooked to make it look like the schools are improving, when in fact it doesn't extend to the fifth grade, and that No Child Left Behind is an unmitigated disaster. They set out to do a story on the school system, but they abandoned it for homelessness because they're sort of reed thin. Prosecutions collapse because of backroom maneuvering and ambition by various political figures, speaking of Clay Davis ... And when a guy like Prop Joe dies, he's a brief on page B5.

That was the theme, and we were taking long-odd bets that very few journalists would even sense it. That would be the critique of journalism that really mattered to me, because we've shown you the city as it is, and as it is intricately, for four years. It was all rooted in real stuff.

Well, to be fair, reporting at a deep level is an incredibly difficult and largely thankless job.

Hardest job I ever had.

You certainly demonstrated the huge gap between a great reporter like Twigg, who gets pushed out, and a mediocre reporter like Templeton. Templeton walks around in the city looking scared, and sure, he's sort of pathetic, but it's also easy to relate to that, and you can sort of see where it all begins.

Good reporting is epic.

But where's the motivation, when you're paid next to nothing and your editor doesn't know the difference anyway?

And how are you going to go more than surface deep if the veterans, the guys who've worked there for 10 or 15 years, the ones who understand the city dynamic, they're the ones being ushered out the door, because they're the more expensive players?

Well, and they also have strong opinions. The yes men will always survive while the cranky pros get axed.

Absolutely. When I went into journalism, there was this naive belief -- although it didn't seem naive at the time, because I was coming in after Watergate and after [journalist David] Halberstam and after a lot of cool stuff -- that newspapers were going to become better and deeper and more sophisticated, and they were going to start acquiring reality in ever larger chunks. And that would be part of my overall critique, which you can't obviously do in the confines of "The Wire" because it's set in the now, it's not set in 1985. But when the papers were fat ... the afternoon papers got killed by TV, but the ones that survived that were the monopoly papers in their town, like the Sun. They were fat. And at that moment, that was when Wall Street became the paradigm. When the chains bought up everything and they took profits.

Making a profit was their downfall, essentially.

Making an 18 percent profit and thinking that there was nothing else on the horizon and you were the only game in town ... You can't tell me that they were saving the money for a rainy day. Nobody knew that the Internet was going to be what it was. Nobody at my paper did, anyway. And now it is what it is, and there is no money, and they didn't spend the window that they had building something that was so essential and so vibrant and so necessary to understanding the world well that you couldn't do without it. Guess what, I'll pay for online advertising. Shit, I'll pay to be part of your Web site for 10 bucks a month. The chance to create a product where the Internet paradigm would've worked and been profitable, it was pissed away.

Did you think about putting the whole question of the Internet into the Sun's story?

It is in the story in the one place it needs to be in. It doesn't need to be anywhere else. It's in there as the economic preamble, when Whiting gets up on the desk and says, "We have to close the foreign bureaus, and we're going to have another round of buyouts. This is a hard time for newspapers. The Internet is free..." -- whatever it is he says.

If you're saying that there needed to be scenes of the Internet interacting with journalism and bringing down journalism, I will now write you a scene: Interior, garden apartment anywhere. A white male, mid-30s, sits at a laptop computer in his underwear, linking to a Baltimore Sun story. He then scratches his left testicle until satisfied and continues to type commentary about that story onto his blog. Cut to drug corner, and on to the next scene.

The impact of the Internet is that it's pulling the froth of commentary and debate off the top of first-generation news gathering, leaving newspapers with only a first-generation role for themselves, which is not enough for them to sustain readers, and so they're losing young readers. By and large, excusing the fact that there are some first-generation journalists going out and acquiring new information directly for the Web, the vast majority of the Internet is reaction and debate and commentary -- some of it brilliant. But I don't run into a lot of Internet reporters at council meetings and in courthouses.

The issue that's being debated here is whether or not a second-tier regional paper -- that once covered its city, that was trying to get better at explaining the nuances and the particular details of life in the streets of its city and in its boardrooms and its council chambers and in city hall -- is becoming thinner and thinner. And what they're able to capture of the city is thinner and thinner. That's what we depicted. And incredibly, the entire onanistic, self-absorbed, psychically wounded, worried-about-tomorrow world of journalism had nothing to say about that.

Obviously, though, your show is given tremendous respect and attention by critics and the media.

I'm not being pissy about it, I'm cracking up. On some level, it's almost perfect that they missed it. I think that a lot of journalists didn't remark on what the coverage was or wasn't, because the reality is that a lot of editors at a lot of these papers are no longer aware of what they're missing anymore. I think normal viewers got it better than journalists.

When Marlo tastes the blood on his arm -- what insights are given into his soul at that moment? Does he even have a soul?

Sure he does. I don't want to be the kind of person to tell you what the movie means. The thing about that scene, it's an homage to the end of a movie I love a great deal, "The Gambler" with James Caan, the modernized treatment of Dostoevsky. I confess we stole that sequence in some ways. It's not the same sequence, it's not like Brian de Palma with "Battleship Potemkin" on the stairs [the Odessa steps sequence used in "The Untouchables"]. It's not like we stole the filmic sequence, but if you look at the end of "The Gambler," there are some clues there.

Was that Marlo on the street at the start of the ending montage? I thought he might've gone back to running a corner.

After leaving the circle-jerk of developers, he walked up on those kids who were telling an Omar story and challenged them. He wasn't on a corner otherwise. He clearly wants his name back, but whether he's going to get back in the drug game? Unstated in the piece.

Avon, Stringer Bell and Marlo are such different leaders. I think it's clear what drives Avon and Stringer, but Marlo is a real mystery, to the end. What drives him?

Power. Totalitarian power. The desire that only dares to speak its name when a human being is sated with money and fame.

No one really gets out unscathed this season, except for Kima Greggs, maybe. Do you think it's possible to work within any of these institutions and remain honorable?

Bunk, Prez, are OK, maybe. Bubbles, of course, though he is an outsider, struggling only with his own addictions. Sydnor will be fine for a minute or two more, maybe. But no, that's the point of this postindustrial American tragedy. Whatever institution you as an individual commit to will somehow find a way to betray you on "The Wire." Unless of course you're willing to play the game without regard to the effect on others or society as a whole, in which case you might be a judge or the state police superintendent or governor one day. Or, for your loyalty, you still might be cannon fodder -- like Bodie. No guarantees. But only one choice, as Camus pointed out, offers any hope of dignity.

Which of the characters will you miss writing for the most?

I think I'll miss writing about Baltimore. That sounds like a cheap answer. For people who haven't watched the show carefully, who think it's just a brutal and cynical assessment of the city, that may sound like a surprising answer. And Baltimore may not miss me writing about it. But I thought we wrote with a lot of affection for the place, and with a lot of sincerity.

There may be other Baltimore stories, and in fact, Ed and I are looking at other things to do, but I'm never going to sprawl a story over a city that way again.

Is this your masterpiece? It would be hard to create anything else that would be as complex as "The Wire."

Listen, I don't even know if it's a masterpiece. Let's see if it holds up for five years. I think it's pretty good, but you're throwing around some big words there, and I'm not just being falsely modest.

You're very Jesus-like when you speak in such a humble way.

That's how the complex works. [Laughs.] I don't know what it is. I think ["The Wire"] will hold up, and I think it'll hold up as a unified 60 episodes. But I could be wrong. Is anything really a masterpiece? Shit's never finished; it's just abandoned, I think Churchill said that about books. That's true about everything.

I thought someone said that about poems. (And before that, art.)

It's a better line about poems than it is about prose. But the show is very pessimistic about the American empire. I don't delight in pessimism. I would be happy if, 10 years from now, "The Wire" is entirely wrong about the direction the country's headed. I'd be happy about that because I live in Baltimore. I'm an American. I have a vested interest in its turning out better, not worse. But I don't know. So let's wait on that masterpiece shit. I'm not quite sure what we built.

I guess history will determine that.

Right, I mean, by the way, it may just be some dusty DVDs on the shelf, when the machines don't play DVDs anymore. It may not even be worth debating.

Just another outdated technology. Plus, our culture is just getting dumber and dumber, so it may not stand a chance.

The proof in that is that a guy with a C-average degree from the University of Maryland and 13 years of covering cops for a newspaper in Baltimore has a television show, and everyone's arguing over whether it's brilliant or not. OK, that's a culture that's in serious decline.

Shares