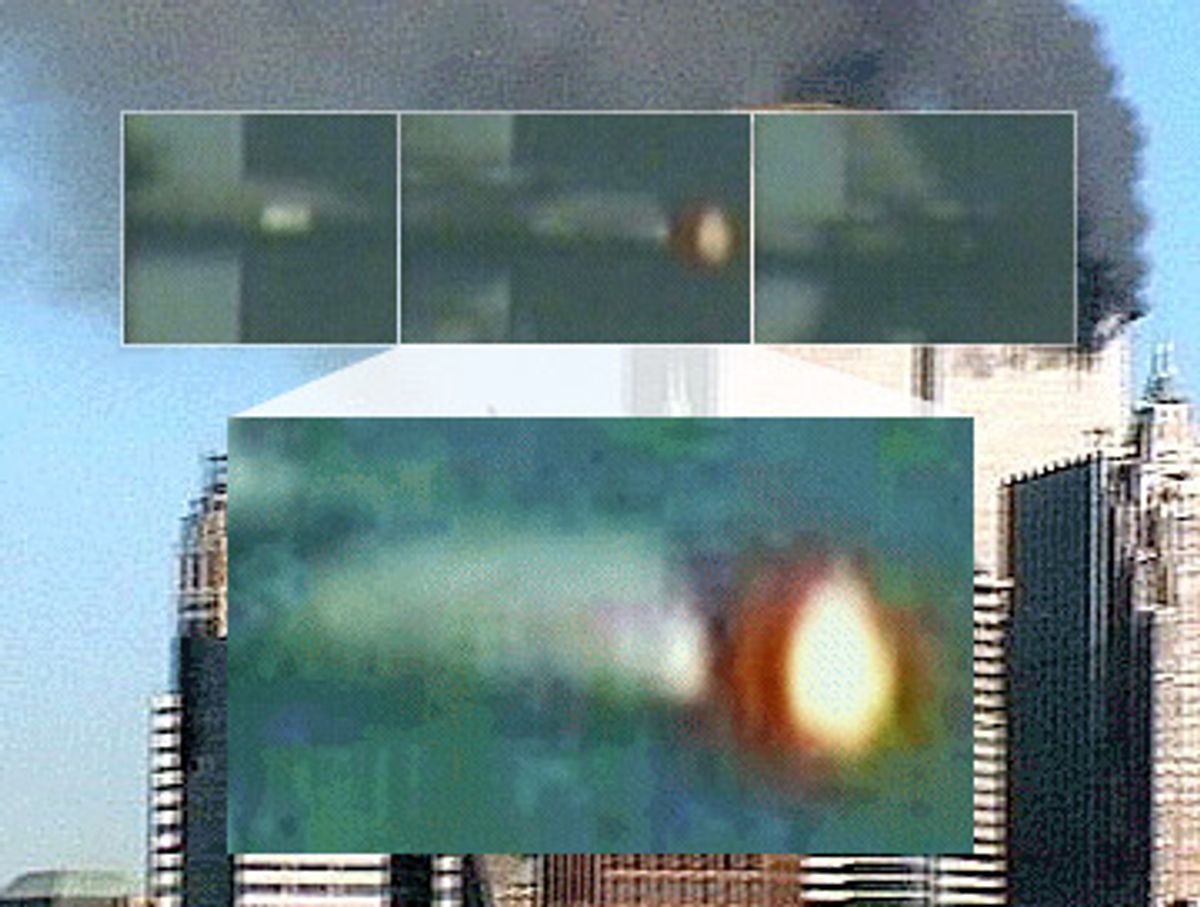

Images from Letsroll911.org

Note: Over the next few days in Machinist, I'll be running excerpts from my new book, "True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society." The book argues that new communications technologies are loosening the culture's grip on what people once called "objective reality." Here, I discuss one aspect of this trend, why the spread of digital cameras doesn't necessarily foster "truth."

Excerpted from "True Enough" by Farhad Manjoo (Wiley, 2008)

In the summer of 2006, I met Philip Jayhan, a member of the self-described 9/11 "Truth Movement," at Conspiracy Con, an annual Northern California gathering of adherents to outré ideas. Jayhan is a clean-cut, chain-smoking fellow in his middle 40s with dusty blond hair and a quick, meandering, argumentative style. When I told him I believed the official theory of 9/11, he raised an eyebrow in a way that suggested more sorrow than anger. Then, on his laptop, he pulled up his Web site, LetsRoll911.org, and played the video clip that long ago prompted him to question everything.

The scene -- it was filmed by one of the many TV cameras aimed at the World Trade Center towers that morning; you can watch it here -- begins with the hulking silver mass of the South Tower filling the frame. In slow motion, Flight 175, the second plane to hit the World Trade Center, jerks into the picture. Then, near the front of the fuselage, an indistinctly shaped bright gleam appears on the undercarriage of the plane. This illuminated slice, Jayhan believes, is the exhaust plume of a missile.

The entire sequence takes place over the course of just a few frames of video -- in less than a split second at the film's full speed. But Jayhan says that in this quick moment, we're witnessing something dastardly: Just before Flight 175 hits the building, a missile jettisons from the plane, falls a few feet away, and then flies straight at the tower.

I couldn't see it. For me, the video was too blurry, drained of color; like so much about 9/11 and its aftermath, the sequence seemed lost in shades of gray. And when I looked into Jayhan's theory later, I saw that several thorough investigations have ruled out the possibility of a missile on Flight 175.

I couldn't see it. For me, the video was too blurry, drained of color; like so much about 9/11 and its aftermath, the sequence seemed lost in shades of gray. And when I looked into Jayhan's theory later, I saw that several thorough investigations have ruled out the possibility of a missile on Flight 175.

Yet Jayhan remains a believer, and he is not alone. Polls show that a large percentage of Americans question the official story of 9/11; an unbelievable number suspect, like Jayhan does, that the government had a hand in the attack.

Here's what's most interesting about this movement: 9/11 conspiracy theorists -- from Jayhan to the provocateurs who produced the popular film "Loose Change" -- all rely on photos to make their case, the same images that the rest of us use to support our version of the story.

More photos used to mean better proof -- a better representation of the "truth." You might reason, for instance, that if only we had better photographic evidence from the Kennedy assassination than Abraham Zapruder's iconic 26-second film, we'd know exactly what happened there. We wouldn't argue -- as many Kennedy researchers do -- about what Zapruder's film means: Does it prove that there are two shooters there, or just one? Does it show that Oswald had enough time to get off three shots, or just the opposite?

In the decades since Kennedy's death, we've achieved photographic ubiquity. Today, billions of tiny cameras record everything, and broadcast it all immediately online. The world, now, is constantly watched, each of us Zapruder himself.

Strangely, though, all these images have not pushed us toward greater collective agreement about what has happened, or what is happening, in the major controversies of the day. Sept. 11 is a primary exhibit, but in other issues, too, photos seem to prompt more disagreement than agreement: Images did not settle, for instance, what really happened between American and Iranian boats on the Strait of Hormuz in January. Indeed, the brilliant pictures that now come at us daily often only blur the truth, casting reality itself wide open for debate.

One cause of this is a phenomenon psychologists call "selective perception," which was described, most famously, in a study by social scientists Albert Hastorf and Hadley Cantril in the early 1950s. The pair set out to determine how an Ivy League football championship game -- in which Princeton trounced Dartmouth -- had been perceived so differently by fans of the opposing teams. Each campus was in an uproar over what each described as the other side's blatantly unsportsmanlike play.

Hastorf and Cantril showed a film clip of the game to groups at each school -- two fraternities at Dartmouth and two eating clubs at Princeton. They asked the students to act as unbiased referees, marking down all infractions they could spot. The results were remarkable: The Dartmouth fans mainly noticed Princeton's errors, while the Princeton fans concentrated on Dartmouth's.

The fans weren't deliberately overlooking things, Hastorf and Cantril stress. This was a matter of visual perception: Each side, that is, really did "see" a completely different game. When one Dartmouth alumnus was shown a film of the game, he decided it must have been badly edited. He'd heard that his side had played dirty, but where were those parts on the movie? He simply could not see them.

To understand how opposing fans saw the game so differently, consider what a football game really is: organized chaos. "There's an instant before it collapses into some generally agreed-upon fact when a football play, like a traffic accident, is all conjecture and fragments and partial views," Michael Lewis points out in "The Blind Side," his fantastic exploration of the modern game. But it's not just car accidents and football plays that are like this; nearly everything is.

Think about a schoolyard at recess, a baseball game, a political debate. Think about a confrontation at sea, a presidential assassination, a terrorist attack. Or just think about all that happened to you yesterday: Every "thing" that occurs is really a million smaller things involving a million people. But which of the million things, and which of the million people, do we notice? And which do we overlook?

Hastorf and Cantril argued that it is the stratified structure of football, and of life, that explains the difference between what the Dartmouth fans "saw" and what the Princeton fans "saw" when they watched an identical movie of the season-ending game. There are countless "occurrences" during a football game, but we only notice one of these occurrences "when that happening has significance," they wrote.

The rub is that not everyone finds the same things significant, so even if we're watching the same event, you and I might see different things. What you notice in a photograph or a video is a function of a personalized calculus -- an idiosyncratic, unconscious filter, built up over a lifetime, that you apply to all that you take in. When the Dartmouth alumnus watched the film of the game, he interpreted the images through a mind reared at Dartmouth. To him, the idea of a Dartmouth footballer playing dirty did not -- could not -- register. So he didn't see it.

Which brings us back to 9/11-doubter Philip Jayhan. Jayhan has long harbored a deep distrust of the government and of the institutions that exert power on the world. Given his worldview, it's clear Jayhan really believes that he sees a missile shooting out from Flight 175.

Or, to put it more accurately, he really does see it. A billion things happened to a million people on 9/11, and if you watch all the videos and listen to all of the audio, there's a lot that you'll find significant, and there's a lot you'll overlook. Some of it you've really got to puzzle out. Jayhan puzzles it out according to his own thoughts about how things work in society. And as a consequence of his ideas about the world generally, he is naturally prone to seeing something in those pictures that I -- as a consequence of my own vastly different beliefs about the world -- do not.

There are, of course, many other ways in which pictures deceive us today -- through digital manipulation, for example, or as a result of selective viewing (when blogs you favor only show you pictures of an event that support your view).

Together, these forces have diminished the power of photographic proof. We think that what we see in pictures -- or what we hear on tape -- gives us a firm hold on fact. But increasingly, the pictures and the sounds we find ourselves believing may only be telling us one version of true.

Shares