We were all wrong about Barack Obama's exotic past.

The same folks who once whispered that B. Hussein Obama was a mole for radical Islam are now decrying his links to an even more anti-American cult: the United Church of Christ.

And it wasn't Honolulu, or Jakarta, or Nairobi that put Obama in touch with folks supposedly bent on undermining heartland values. It was the heart of the heartland's biggest city: the South Side of Chicago, where Obama launched his political career. The South Side is responsible for the black nationalist preachers and violent radicals-turned-professors whose sound bites and rap sheets have now mired Obama in the worst patch of his presidential campaign. But without them Obama wouldn't have had a seat in the state Senate, much less a shot at the White House. And now the black street cred and lefty bona fides they provided, so crucial to Barack Obama's early local success, are proving corrosive to his national ambitions.

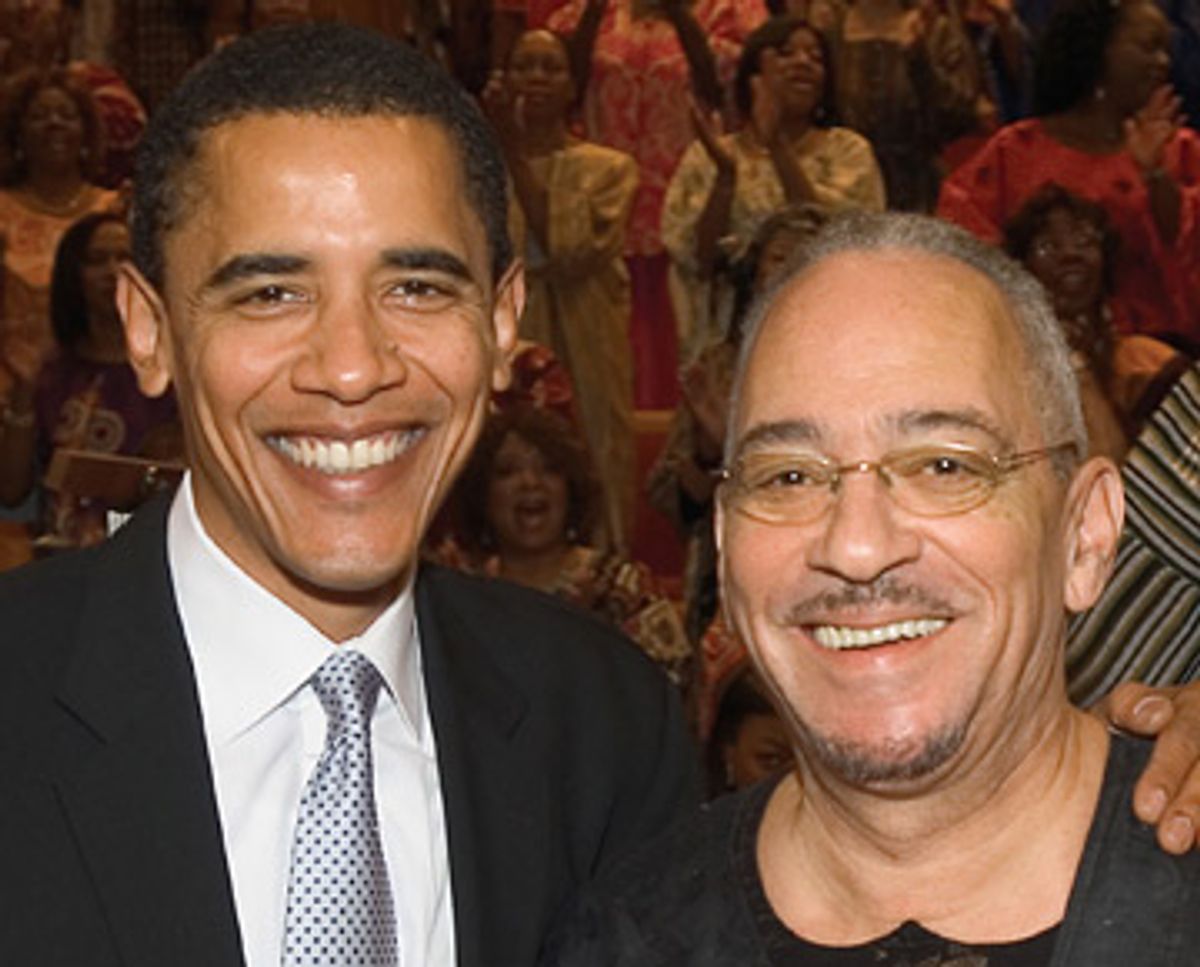

Obama suffered his biggest embarrassment of the campaign last week when his pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, was shown on ABC News changing the words of "God Bless America" to "Goddamn America."

Wright is the recently retired pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ. One of America's most liberal Protestant denominations, the UCC runs TV ads welcoming gays who can't find a pew elsewhere. With 8,500 members, Trinity United is its largest church. Wright built that congregation with a black Christian philosophy, which connected Bible stories to the struggles of an oppressed people. He was like an African-American rabbi, promoting his flock's pride in their heritage by preaching in a dashiki and organizing trips to Africa. He tended to their worldly needs with a day care center, a credit union and a drug and alcohol program.

As a young biracial man building a black identity, Obama found Wright's Afrocentrism appealing. The first time he visited the church, in 1985, he saw a "Free South Africa" sign on the lawn. With a sermon titled "The Audacity of Hope," Wright relieved Obama of his agnosticism, gave him the theme of his political career, and introduced him to the preaching style he uses so dramatically on the stump.

But joining a black mega-church was also a quick way for a young man on the move on the South Side of Chicago to address some gaps in his résumé.

In any American town, it's not uncommon for anyone launching a business enterprise that depends on name recognition and personal contacts to join the Lion's Club or the Rotary and one of the biggest churches on Main Street. In "Audacity of Hope," Obama is talking about networking when he describes what brought him to Wright's church in 1987.

He was a community organizer then, and one of the black ministers with whom he was consulting suggested that the work would go more smoothly if he joined a congregation. "It might help your mission," said the pastor, "if you had a church home ... It doesn't matter where, really." The pastor was talking about Obama's community organizing mission, but he was also giving him good advice about politics.

When Obama picked a "church home," he chose one that helped him with another weak spot in his biography. Before Obama joined Trinity United, Rev. Wright warned Obama that the church was viewed as "too radical ... Our emphasis on African history, on scholarship..." But Obama joined anyway. With that act, he had become significantly blacker -- and more like local voters. Part of the cultural divide between the half-Kenyan Hawaiian and his Chicago neighbors, most of them products of the Deep South's black diaspora, was bridged.

Twenty years later, Wright has been caught saying stuff that some black folks say when white folks aren't listening. Wright built one of the biggest congregations on the South Side with his black empowerment rhetoric. His parishioners didn't necessarily find it outlandish when he thundered that the U.S. government cooked up HIV as a form of inner-city genocide, or that America brought 9/11 on itself. The government hasn't always been a friend to blacks. Whites so seldom venture into black churches, however, they were shocked to hear Wright's politically inspired riffs.

It does not seem credible for Obama to claim equal surprise, to claim unfamiliarity with Wright's more aggressive opinions. Obama quoted Wright at length in "Audacity of Hope" -- and took the name of his book from one of the first sermons he heard Wright deliver. As he wrote in "Audacity of Hope," when he looked through the "Black Value System" that guided Wright's church, he saw "A Disavowal of the Pursuit of Middleclassness." That first sermon included a comparison of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre in South Africa, which claimed 69 lives, to Hiroshima.

In fact, Obama seems to have known that Rev. Wright was not someone he could bring to Iowa. Last year, Obama asked his pastor to deliver the invocation before his presidential announcement in Springfield, Ill., then withdrew the offer. As white America learned more about Wright, Obama started comparing him to a crazy uncle. Finally, last Friday, he condemned his statements and kicked him out of the campaign. Wright did his final service to Obama by retiring on Feb. 11, a month before ABC aired his sermons.

But Trinity United is only part of Obama's South Side baggage. Wright may seem racially divisive; Hyde Park, the neighborhood north of Trinity United where Obama eventually settled, is about coexistence. In a city famous for de facto segregation, Hyde Park is biracial -- and intellectual, and earnest, and liberal unto the point of lefty. Hence the lesser of Obama's recent unpleasantnesses: Outside of a Politico article and some huffing and puffing on conservative blogs, the outrage over Obama's ideologically incorrect white friends has not reached Wright-ian proportions, but there is always time.

Walking past the brownstone two-flats on Woodlawn Avenue, you can hear the occasional Sonny Rollins riff unrolling from the open windows of the book-lined sun rooms. When Harper Court still had chess tables, you could watch black blitz hustlers smoke nerdy University of Chicago students, hooting, "I want them panties off!" as they swept away bishops and rooks. (The tables were torn up after the chess scene got too rowdy.) You can still lunch on the $6 mac and cheese at Valois Grill ("See Your Food"). Priced for the budgets of grad students and winos alike, it inspired the great book "Slim's Table," a study of the wary relationship between the campus and the ghetto. Hyde Park just lost its food co-op, but it still has one for the other essential of life: the Seminary Co-op Bookstore, an underground warren of books with colons in the titles, has sections devoted to "gender studies" and "epistemology."

Hyde Park's intellectual life has been dominated by two contradictory strains. The first is neoconservatism: Allan Bloom wrote "The Closing of the American Mind" at U. of C., and Paul Wolfowitz studied under Leo Strauss. The second and by far numerically superior force is the humorless liberalism that makes every elite campus such an anal-retentive place. Hyde Park is our most uptight neighborhood. In 1995, the Princeton Review named U. of C. America's "worst party school," inspiring this joke: "Q: How many University of Chicago students does it take to screw in a light bulb? A: Quiet! I'm trying to study in the dark." The neighborhood invariably elects a goo-goo alderman who pulls killjoy stunts like, you know, asking to see what's in the mayor's budget before voting on it. The most famous, Leon Despres, who just turned 100, once spent five days at Trotsky's place in Mexico City. The only reason Hyde Parkers don't drive Volvos is that they're too long to parallel park.

Obama began teaching constitutional law at U. of C. in 1993. When he decided to run for state Senate, in 1995, his district encompassed Hyde Park, as well as the weary black neighborhoods to the west, with threadbare street corners that might hold a liquor store, or a chicken shack. (It did not include Trinity United.) One of his first campaign events was at the home of Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn. Ayers and Dohrn were the '60s most glamorous radical couple: the Bonnie and Clyde of the Weather Underground, they spent 11 years underground after an accidental bombing that destroyed a Greenwich Village townhouse, killing three of their comrades. Ayers came from an upper-class background -- his father was CEO of Commonwealth Edison -- so when he came in from the cold, he didn't do prison time, the way some biker toolbox bomber would have. Instead, he became a professor of education at the University of Illinois-Chicago, and a fixture in Hyde Park liberal circles. The outgoing state senator, Alice Palmer, introduced Obama to local activists at the home of Ayers and Dohrn. Obama later served with Ayers on the board of the Woods Fund, which supports projects in poor Chicago communities. Ayers is also a member of Public Square, which organizes events that combine arts with social justice.

"Bill and Bernardine are respected members of the community," says a friend of the couple. "He's extremely involved in education policy nationally."

Another acquaintance, though, calls him a "narcissist," because he promoted his memoir "Fugitive Days" by saying, "I don't regret setting bombs. I feel we didn't do enough." Ayers posed for Chicago magazine with an American flag wadded at his feet.

In Hyde Park, Obama also met Rashid Khalidi, who recently became the first Arab-American scholar to make the pages of the National Enquirer, where he was called "a harsh critic of Israel" in an article titled "Obama's Secrets."

In 2000, when Khalidi was a professor at U. of C., he held a coffee for Obama's congressional campaign. I was at the event, which Obama attended with his wife, Michelle, and their toddler Malia. Khalidi's wife, Mona, set out pita and hummus and Khalidi, a Christian Arab born in New York to a Palestinian father and a Lebanese mother, praised Obama in unaccented English. Khalidi was head of the Center of International Studies, so his support suggested Obama was a faculty darling. There was talk that year that Obama was backed by a "Hyde Park Project" -- a group of well-funded, mostly white intellectuals aiming to push him up the political ladder.

Khalidi is a proponent of a Palestinian state, and has represented Palestine at international conferences, but he also recognizes Israel's right to exist.

Like Ayers and Obama, Khalidi was a member of the Woods Fund board, where he granted $75,000 to the Arab American Action Network, which was run by his wife. The AAAN is a social service agency aiding Southwest Side Arabs, but the right-wing Web site World Net Daily nonetheless has insisted it is anti-Israeli. That wasn't radicalism, it was nepotism, Chicago style.

Obama's tenure as Hyde Park's state senator gave him two advantages he has used to become the Democratic front-runner. The first is his ability to build a biracial coalition. Representing the campus and the 'hood, Obama had to appeal to educated whites and inner-city blacks. Those groups are now the pillars of his presidential support. As a state senator, he promoted bills that pleased both constituencies: opposing racial profiling, reforming death penalty laws, stiffening ethics requirements for legislators, providing health insurance for poor children.

Obama has also benefited from the district's leftist, academic bent. In Hyde Park, he ran with a crowd that harshly opposed this country's policies in the Middle East. Khalidi has gone so far as to say "we owe reparations to the Iraqi people." When Obama spoke against the Iraq war in 2002, it was hardly a gutsy stand. (He didn't have to take a stand at all, since the Illinois General Assembly can't declare war on foreign countries.) But it looks good now next to Hillary Clinton's "aye" vote. Obama comes off as a principled progressive because he represented a district that demanded clean government and liberal social policies -- values cherished by activist Democrats.

To Obama's credit, he hasn't repudiated anyone from his past. His campaign strategist, David Axelrod, admits that Obama and Ayers are "friendly." And Obama denounced Wright's comments without rejecting the man himself. How can he? Wright played an important role in shaping him as a politician. Ayers and Khalidi nudged him along the way. To apologize for knowing them would be to apologize for who he is: an African-American, a Christian, a city dweller, an academic, a liberal. Most of those would be exotic qualities in a president. And maybe that's the real problem.

Shares