In the years between Mary Lou Retton's historic victory at the 1984 Olympics and Kim Zmeskal's dominance in the early 1990s, American gymnastics was in a bad way. Most of our gymnasts lacked the finesse of their counterparts in Eastern Bloc states like Russia and Romania, where children were plucked from their homes almost as soon as they could walk, and U.S. coaches struggled to produce another breakout star. Jennifer Sey was one of their best hopes.

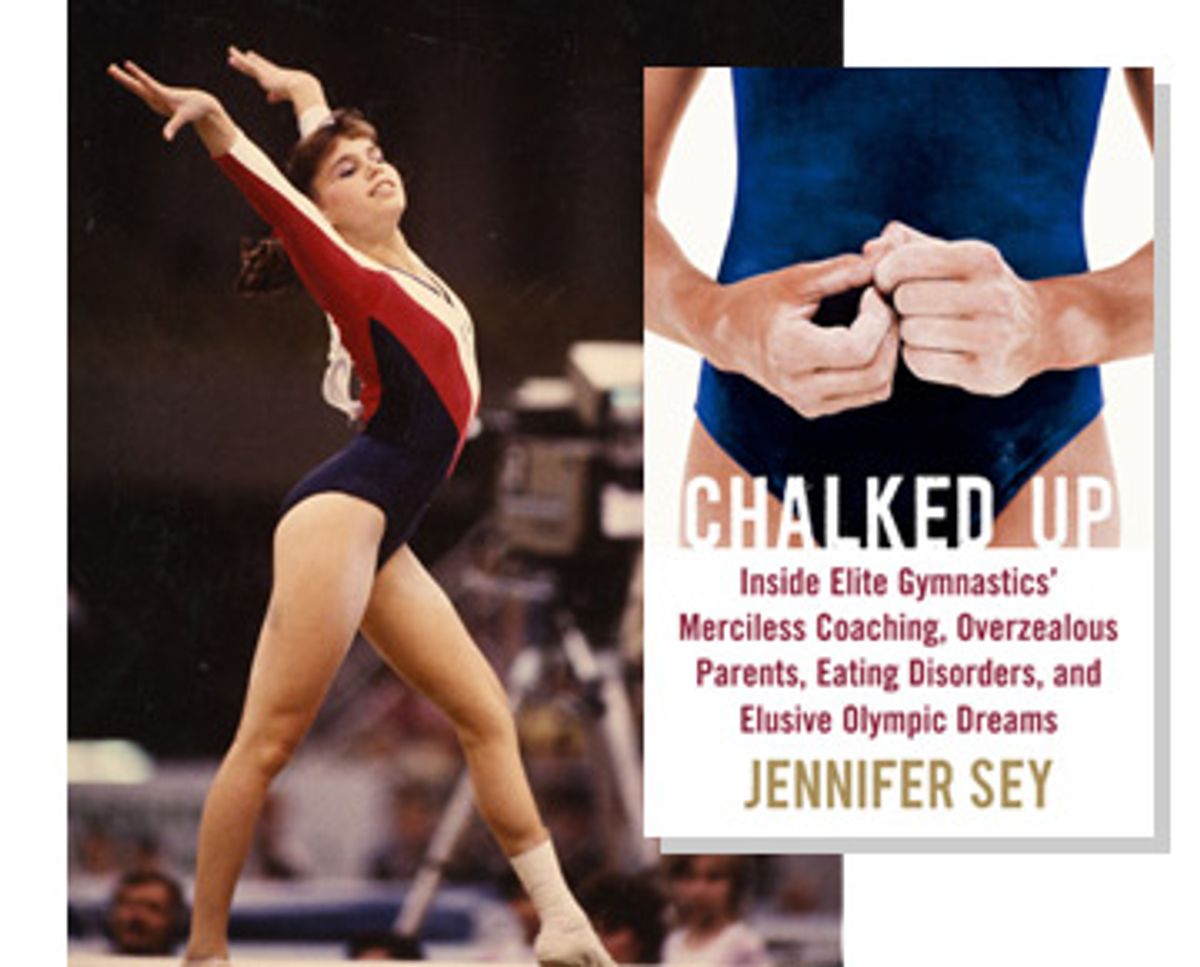

At 15, Sey left her New Jersey home for the Parkettes National Gymnastic Training Center in Allentown, Pa., where she boarded alone in an unheated room in exchange for a chance to become a champion. Under the tutelage of Bill and Donna Strauss, a husband-and-wife coaching team notorious for producing winners by any means necessary, she accomplished just that -- nabbing the U.S. National title in 1986. But Sey was never quite talented or powerful enough to be hailed as the second coming of Retton and eventually, burned out by the pressure to stay skinny and the pain of competing on barely healed broken bones, she retired.

In her new memoir, "Chalked Up," Sey recounts the casual brutality of the sport to which she devoted her childhood. There was the coach who hurled a folding chair at a girl who couldn't perform a difficult maneuver on the uneven bars, and the one who used the gym's loudspeaker to humiliate a 10-year-old for gaining one pound. Sey herself spent the last few years of her career on a fruit and laxative diet, working out for eight hours a day while recovering from a series of increasingly nasty injuries, including a clean break of the femur, the strongest bone in the body. Eating disorders were rampant in the sport, and physical and sexual abuse not uncommon, despite -- or perhaps because of -- the fact that women's gymnastics is dominated by little girls.

Sey spoke with Salon by phone from her home in San Francisco.

What struck me when reading your book was how incredibly hard it is to protect young gymnasts when there are so many incentives for coaches and other adults not to act in the kids' best interests.

I think this is tied to our culture as a whole and how we prioritize winning over everything else. That's why you see steroid use. It's even related to corporate malfeasance -- winning is the most important thing, so the ends justify the means. The problem is exacerbated in gymnastics, because the girls are so young that they're ripe to be taken advantage of. It doesn't happen all the time -- I was just writing about what my experience has been -- but it is a powder keg of circumstances.

Is it possible that you were just the victim of rogue coaches? I know the Parkettes Training Center has a particularly bad reputation -- it was even the subject of an unflattering CNN documentary in 2003.

[This behavior] is endemic to the sport. I think my coaches employed some tactics in my training that were pretty tough to take, pretty aggressive and harsh. They were known at the time for being incredibly tough on us about our weight, which I think has been tempered over the years. But I wouldn't want to make any sort of judgment that they're better or worse than anyone else. I think their perspective is, "You come to us to become champions, and this is what will be required."

Were they actively encouraging you to develop an eating disorder?

Yes, absolutely. I don't think they would say, "Go throw up," or "We want you to be anorexic," but the fact is that they were asking us to do things that were impossible without engaging in behaviors that were dangerous. People weren't quite as sophisticated in their understanding of eating disorders then as they are now, so I don't know if they understood that there were long-term psychological and physical effects.

Back in the early '90s, Christy Henrich, whom I competed with, died from anorexia. She'd been told that she wasn't a viable athlete at the weight she was competing at, and she proceeded to whittle herself down to about 55 pounds. There was sort of an outcry, and the sport came under scrutiny for that, and there has been a shift, which is great. I also think the skills [today] are so incredibly difficult that they require a lot of power, and that has prompted a change. The sport can be a bit trendy, and certain body types come in and out -- I hope this one sticks, but we'll see.

I'm fascinated by what made your coaches Bill and Donna Strauss tick -- you portray them as so nasty to the young girls in their care, and so oblivious to their mental and physical health. Does it bother you that they're still coaching kids?

I was willing to take [the abuse] because I wanted to win. So I don't actually have a problem with them coaching. What I would like is for the methods they employ around weight to be modified -- that wreaks havoc on young girls. I would like for there to be some guidelines for no training while you're injured. I called [the Strausses] out because they were my coaches, but I don't think they are so different from others who coach at the highest levels today. What made them tick was that they wanted girls who won, they wanted their club to be the best, and that clouded their vision.

You portray the Parkettes team doctor, Dr. Dixon, as something of a charlatan, a man who deferred to your coaches about medical decisions and sent you back to the gym to train with a concussion in one instance, a freshly broken ankle in another.

The way he would probably present himself is that he aided you in getting back to your goal. It's easy to look back and say that as a doctor, he should have had my physical and mental health at heart, but he saw my best interests as getting me back into the gym so I could compete and win. I think that most orthopods and specialists who treat high-level athletes are probably very similar. If you talk to the doctor for the San Francisco 49ers, they probably send people into play who aren't 100 percent. What made the situation unique is that we were children.

In one scene, you describe the indignity of getting bawled out about your weight by the National Team coach, Don Peters, when you were actually extremely tiny and suffering from an eating disorder. But in the same passage, you describe two fellow gymnasts, Pam and Yolande, as "lumber[ing]," "lumpy" and "elephantine."

The fact is, when you have an eating disorder, you don't see things clearly -- body dysmorphia is part of the disorder. I thought of myself as not nearly as thin as I would've liked to be, and I saw other people in an unclear way as well. What I was trying to do is put you into the mind-set I was experiencing at the time. I looked at those girls, and I thought they were bigger than me. They weren't big, but I was 16 years old, and I didn't see my body clearly. I didn't have the luxury of any kind of objectivity. I saw them as heavy, because the accepted aesthetic was thinner.

Do you still see that?

No! I've seen pictures since, and I think it's horrendous that I could've thought that. But if I recall, I did indicate that a girl was elephantine within the sport of gymnastics, within that world. Yolande was heavy -- she was 10, 15 pounds heavier than the average girl who competed at that level. I don't think I was casting aspersions so much as providing context.

Throughout the book, you make elliptical references to male coaches who are attracted to young girls and imply that your own personal coach, John, was one of them. What did you mean when you said that he was "lewd and lascivious" and "may have liked being near all the barely dressed teens, but … never explicitly let on"?

He was never inappropriate with us, but he was a really flirty guy, and we all saw that. And sometimes the women he flirted with were very close to our age -- 18, 19 years old, and we were 15 or 16. There were a lot of things he did that made me feel weird -- he was a weird guy. The conditions of the sport are strange, and that was what I was trying to say. Most men that coach women gymnasts have never been gymnasts themselves. So I always wondered, even as a child: Why do these men want to coach little girls? In some instances, it's purely financial. But I think in the minority of cases, there are men who are interested in little girls.

You repeat a rumor that Don Peters had a sexual relationship with a young gymnast in his care. That's a pretty explosive charge -- do you have any evidence for it?

I was trying to point to what our mind-set was, what it was like for us. We understood that there was a strong likelihood that there was an impropriety there. Whether or not it was true was kind of beside the point. We lived in an environment where there was some illicit behavior suspected, and none of the adults would intervene. Nobody cared enough about her to dig into it. Whether it was true or not, somebody should have said something, somebody should have done something, somebody should have asked.

Do you think it was true?

I don't think it's pertinent to the story I was trying to tell.

What if Don reads the book and feels that you are libeling him?

I'm sure he will read the book -- I think most coaches will. It was a hot rumor, and I was trying to explain the conditions we were working under, so I don't have a problem if he reads it. My intent has never been to write an exposé about all the tawdry things that happen in gymnastics, just to explain what it was like for me and for girls like me.

But it will be functioning as an exposé ...

Absolutely, I understand that's how people will read it.

What kind of reaction are you anticipating from coaches and others in the gymnastics community?

For people who love gymnastics, who want to see it thrive, I think they'll say, "Yes, this exposes a dark side to our sport, but we have practices and regulations in place to try to overcome some of these things." I think that people who feel defensive about it will be very angry. The Strausses, who have an advance copy, are already quite defensive about it. But this is what happened to me. I'm not trying to bring them down, and I'm not trying to bring their gym down. But all coaches have an obligation to realize that they're not just raising champions, they're raising young women. Hopefully they'll maybe think twice about some of the practices they might employ. I love the sport -- I don't want the sport to go down. I just want people to think differently.

Shares