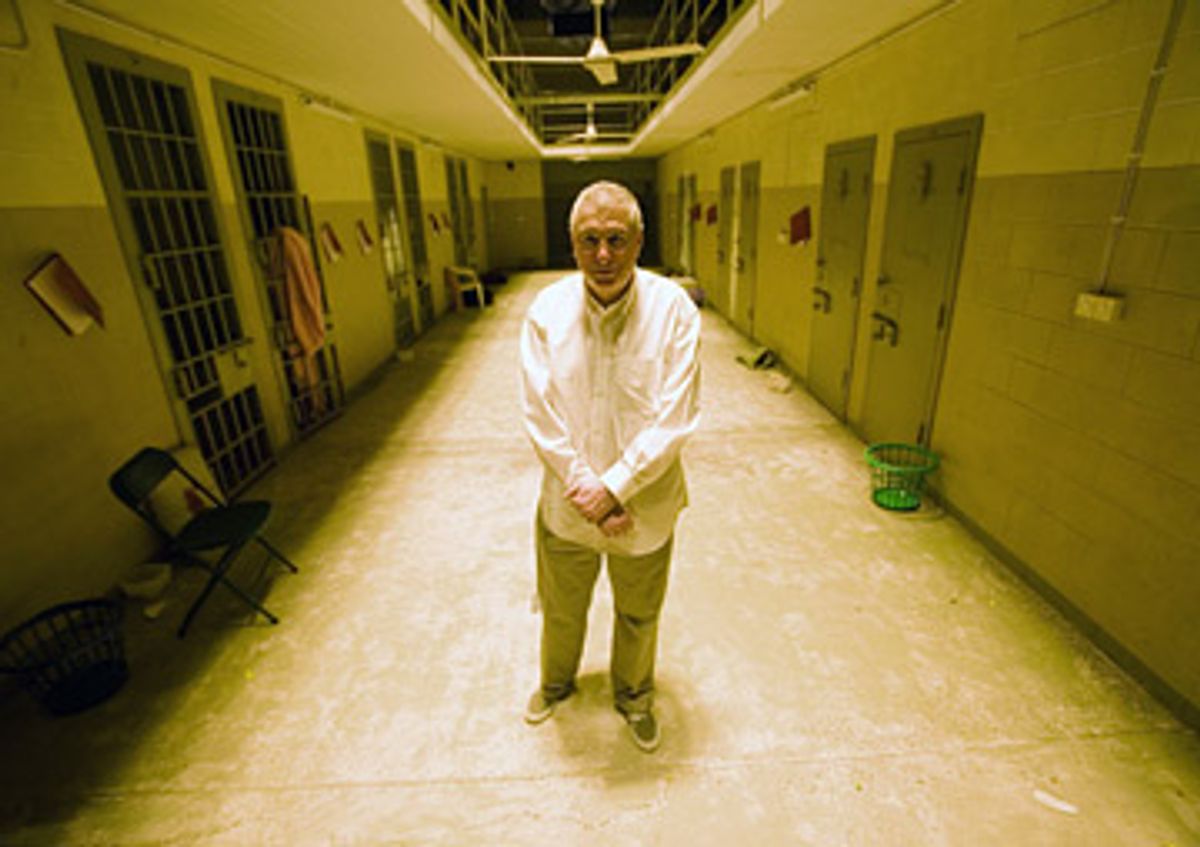

Tony Diaz, a former military-police sergeant who served at Abu Ghraib, stares into Errol Morris' camera and speaks in baffled tones about being called into a shower room at that notorious Baghdad prison where CIA interrogators were beating an Iraqi detainee to death. Diaz says he did not participate in the man's interrogation and did not beat him; he was ordered to hold the man up and help secure his arms, and he followed those orders. While he was doing that, drops of blood fell from the detainee's battered face onto Diaz's uniform, and that troubled him. He hadn't done anything wrong, he told Morris, yet the blood made him feel responsible.

I don't mean to demonize Tony Diaz. Virtually alone among the interviewees in Morris' new film "Standard Operating Procedure," an artful, meditative investigation of the infamous Abu Ghraib photographs and the circumstances that produced them, Diaz seems to be wrestling with his conscience, after his own bewildered and evasive fashion. (Morris has also co-authored a book of the same title with New Yorker staff writer and Paris Review editor Philip Gourevitch, to be published next month.)

Everybody else who was there, from former Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski, who commanded the M.P.'s at Abu Ghraib, down to the specialists and privates who took the fall for the abuses committed there -- including Megan Ambuhl, Sabrina Harman and Abu Ghraib poster-child Lynndie England -- enthusiastically points fingers and passes the buck: Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld did it; I fell in love with the wrong guy; there were black-hat government agents I couldn't control; I was just following orders.

As Morris said to me in our recent interview, welcome to the human species. But at the risk of sounding like a terrorist-coddling America-hater, the human species in our country, circa 2008, has some issues with moral clarity. If I believed that there was any public appetite for a movie like "Standard Operating Procedure," I might also believe that it would spark a public conversation about responsibility for the crimes and abuses committed in our name -- some we know about and a great many more, one suspects, that we don't. If we're honest with ourselves, which is a pretty tall order, we might find ourselves in Tony Diaz's position: We didn't do anything wrong, so how did that blood get on our clothes?

But it's evident, as Morris has observed elsewhere, that the American people don't care about torture. We don't mind it, in fact, as long as we don't have to see it or think about it. If it's called something else, like "harsh treatment" or "stress positions" or "special tactics," so much the better, although I doubt the euphemisms are fooling anybody. Morris' mission in "Standard Operating Procedure," in part, is to restore human dimensions to people like Ambuhl and England and Harman who have arguably committed evil and contemptible acts. Some critics have suggested that Morris is justifying their conduct by placing it in the broader context of the paranoia, conformity and oppression that afflicted the military campaign in Iraq and Abu Ghraib in particular.

I don't see it that way. Intentionally or not, Morris' interviews with these confused, vacuous and morally rudderless people felt to me like a sweeping indictment of those of us who are their fellow citizens and who share the culture that produced them. Lynndie England, in particular, is pretty hard to take. Out on parole after three years in prison, she looks battered and puffy, closer to 40 than 25, and remains completely without insight into how her affair with former Cpl. Charles Graner (the alleged mastermind of many of the abusive acts shown in the photos) led her to collaborate in the sexual humiliation and ritual degradation of Iraqi detainees.

Listening to her talk, I felt only contempt and disgust -- contempt for this beaten-down, dull-witted woman for the things she has done and disgust with myself for being unable to muster more than a faint flicker of compassion. Unfortunately, the people who really deserve our compassion, the Iraqi men brutalized at Abu Ghraib and other places, are absent from Morris' film. He says he tried to find the men in the photographs, but many remain unidentified and others have disappeared. (As for Charles Graner, he remains in prison, and Morris' requests to interview him were refused.)

To some degree, Morris is motivated by a Susan Sontag-style epistemological critique of photography: We think a photograph offers us the unvarnished truth, and all it really gives us is a moment, divorced from context and history. While this does not strike me as the most urgent element of "Standard Operating Procedure," he makes a persuasive case that many of the Abu Ghraib photos don't show us what we think they do, and that some of the episodes depicted were staged specifically to be photographed (and might not otherwise have occurred).

One especially shocking set of photos shows Sabrina Harman, wearing an awkward smile and giving the thumbs-up signal, next to the corpse of Manadel al-Jamadi, the man Tony Diaz saw beaten to death in the shower room. Despite the grotesque inappropriateness of her gesture, Harman had nothing to do with his death, and at least in her mind she was helping to expose the crime. Morris makes the valid point that without her photographs, al-Jamadi would simply be another Iraqi who disappeared into U.S. custody and never came back.

I don't think Morris is arguing that Graner, England, Harman, et al., are morally blameless, but he is suggesting that they were scapegoated for revealing the systematic torture that was already happening on a broad scale at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere, rather than covering it up. They were unprepared, poorly trained soldiers sent into a frightening and lawless "Lord of the Flies" environment, and they were unable or unwilling to resist it. There's enough blame there to pass around.

Perhaps the most chilling moment in the film arrives when Brent Pack, a former special agent with the Army's Criminal Investigations Division who analyzed the Abu Ghraib photos, discusses the most famous ones. Naked men piled in a human pyramid, forced to masturbate, or pulled around on a dog collar? Yes, those incidents count as torture. But a naked man shacked to a steel bed frame with women's panties over his head? Or, most famous of all, the hooded man known only as "Gilligan," standing on a box with fake electrical wires on his fingers? Those things are not torture. That's standard operating procedure.

In person at a New York hotel, Errol Morris was alternately friendly and argumentative, and nearly as evasive as some of his interviewees. As a way of lampooning his critics, he badgered me into apologizing for my prejudices about the Sabrina Harman photos -- prejudices that, with the luxury of hindsight, I'm not sure I ever held. As you can probably tell, the apology was not heartfelt or authentic at the time, but now that I look at the interview again, I won't retract it. I've got plenty of things to atone for. Hey, what the hell is this stain on my shirt?

[To listen to a podcast of this interview, click here.]

You know, in terms of the Abu Ghraib photographs -- how they came about, who is to blame and the climate in which all of it happened -- I find myself almost more bewildered having seen your film than I was before. Is that a good thing?

You have to explain that a little bit more to me. Why are you bewildered?

Well, the question that a lot of people are going to want answered is about who is to blame for the things we saw in the Abu Ghraib photographs. In a sense, your film really isn't about that, is it?

No, it's not. Everybody is, of course, fascinated by that question. Who can I blame? Who can be blamed for this? Who is responsible? Whose fault is it? Questions really not so easy to answer. Part of the problem with this whole story is the photographs seemingly gave us someone to blame. I believe Bush won reelection in 2004 because of the photographs. The day that the Abu Ghraib photographs became public, he could say, "This is the worst day of my presidency." But on the flip side, he had someone to blame for the failure of the Iraq war effort.

The so-called seven bad apples.

The so-called bad apples. You want to know why the war is going south? You want to know why the insurgency is growing? You want to know why the Arab world hates our guts? These guys.

A few people who did a few bad things.

These guys and the photographs that they took that made America look bad. It became an odd blame game. Doesn't matter if you're on the left or on the right -- Salon, I know, is an extreme right-wing publication.

That's right.

It doesn't matter whether you're on the left or the right, these guys are monsters. If you're on the left, you say they're monsters because of Bush and Cheney and Rumsfeld. If you're on the right, they're monsters because they're monsters, they're bad apples. On their own initiative, they chose to do these things that you see depicted in the photographs. What I've tried to do is go beyond that. One of the things that fascinates me about the story is that no one looked beyond the pictures. They saw the pictures and that stopped everybody dead in their tracks. Everyone had an opinion about them. Everyone thought that they knew what was being shown in the photographs, everybody thought they knew what these photographs were about. I felt I didn't.

It surprised me then that no one had ever really talked to any of the people who took the photographs about, "Hey, what did you think you were doing? What's shown in this photograph? What's this photograph about?" Any of that. So that's the genesis of the film; it's trying to contextualize photographs that everybody in the world has seen but nobody knows anything about.

As you develop more and more testimony and interview a lot of people who were present when those photographs were taken, the situation becomes murkier and murkier. I think that's fair to say. All these people who weren't trained for the job were being told to extract information, or make it possible for others to extract information. One of the things that disturbed me greatly is the idea that there were prisoners in Abu Ghraib who were never officially registered, and mysterious people from "other government agencies" whose status was not understood by the soldiers.

Yes, the OGAs.

What the hell was going on there? That's verging on nightmarish fiction about the clandestine operations of the U.S. government.

I would not say verging on nightmarish fiction. I would call this an actual nightmare. I have often described the movie as a nonfiction horror movie. And it is. It was a descent into nightmare. In many ways, I think the entire country is descending into a kind of nightmare because -- big surprise -- I think these photographs have something to say about the entire war effort and something to say about us as a country.

Not something good.

Well, I will allow you to decide. How about this? Something potentially not good.

You interview, among others, the infamous Lynndie England, the young woman who was seen in many of the photographs, and took a lot of the photographs. Also Megan Ambuhl, Sabrina Harman and others who were there. It seems as if you've tried to humanize these people, make them appear as familiar, ordinary Americans. Is that fair?

Yes, it is. It's taking people that everyone looks at as monstrous and bringing them back into the world of people, like you and me. That in itself is going to be controversial.

It already is. I know people who are saying, "He's trying to exonerate them, to say they're blameless because it was Cheney and Rumsfeld that created the situation ..."

That is not true. I do not see these people as lily-white, as blameless, as devoid of responsibility or choice. But I do think that many of the pictures have been misunderstood. That's not the same thing as saying that I think that they share no responsibility for what happened there. I don't believe that.

Going beyond that question that we talked about at the beginning, of who is ultimately to blame, the question of responsibility kind of tortured me as this movie moved forward because ...

Good!

Because there isn't a single person in your film who seems willing to take responsibility for their role, be it large or small.

Well, this is, by the way…

Everybody is passing the buck to someone else.

Yeah, well, welcome to the human species. [Laughter.] What interests me is that we look at things and we want them instantly simplified for us. We want to be told that this person did X, Y and Z and now they're sorry for it and they'd like to apologize, they'd like to ask your forgiveness. When I made "The Fog of War" ...

Your film about Robert McNamara, the former secretary of defense, which won an Academy Award.

Yes. I was asked repeatedly, "Is he sorry? Did he express remorse? Why didn't he say he was sorry and express remorse in the film?" Of course, the whole film is about Robert McNamara's feelings of remorse and regret. But people want a certain kind of morality play. They want their feelings of right and wrong to be unambiguously affirmed. And if it isn't done they tend to get pretty goddamn nasty. I don't see it as my job to get people to say they're sorry. Well, maybe I could try it on you. This is an opportunity I could avail myself of, that I haven't done so far. Are you sorry for this interview?

Not yet.

Would you like to apologize to me right now and get it over with?

I'll save that for another occasion.

I think you should do it now. I know it's going to be very, very difficult for you.

But you think it will be therapeutic in the long run?

I think it's going to help you even more than it's going to help me.

I think I'll pass.

And I'm your friend!

Will you be more my friend if I apologize to you?

I think I'm going to be your friend regardless, I want to say that upfront. But I would like to see you become more of who you are by apologizing to me now.

So this is what people wanted you to do to Lynndie England, for example?

I don't know what the hell people wanted me to do. I know I don't want to do that. Also I had these fantasies -- OK, McNamara is described as the chief architect of the Vietnam War. Now, whether you buy into this or not, let's say he is for the sake of argument. You want to blame someone for the Vietnam War? Let's pick this guy.

So I guess the goal of the interview was, Robert S. McNamara at some point says to me, "Errol, I'd like to apologize for the death of the 2.5 million Vietnamese in the Vietnam War." I ask myself, do I want to hear him say this to me? And my answer? No! I don't want to hear this. First of all, who in the hell am I? I'm a Jew from Long Island. I am not a Catholic priest. I don't want to hear your confession, I don't want to hear you apologize, I don't want to hear you say, "I'm really, really, really sorry." I just want you to tell me your story. I just want to have some kind of access to your skull, as it were. I want to be able to see how you see the world, how you think. If part of that is the excuses you've made for yourself for your behavior, fine. That's part of the deal. I welcome that information.

But by the way, if at any time during the interview you feel the need to apologize to me, you can interrupt at any time and just say you're sorry.

I'll bear that in mind. I wanted to ask you about the question of photography, which plays a big role in this film. You've said …

Are you sorry about photography?

I'm very sorry about photography. I'm sorry that I trusted photography, apparently. One key to your film is the idea that photographs don't always tell us what we think they tell us. We jump to conclusions about them that may not be supported by the evidence, once we know more.

Yeah, that's correct. They tear a piece of reality away, you don't see anything more than the picture. It's kind of obvious but it's forgotten. You don't see above and below, to the left and to the right. You don't see before and after. You don't see all those things that weren't photographed. You see a photograph, you think, "I've seen everything," when you have seen very, very, very little. In fact, you may not even see what's in the frame of the picture. The Sabrina Harman picture of the smile and the thumbs up [with al-Jamadi's body]. Good lord, I'm talking to Salon. You have outed more of these pictures over the years than anyone else. It's kind of part of the Salon brand, the photographs of Abu Ghraib. This picture, easily found on your site, of Sabrina with her thumbs up and the smile.

Next to a dead guy.

Next to a dead guy, al-Jamadi. Now, people, OK, here's a chance for you to say you're sorry. I've been looking for it. You looked at that photograph, and what did you think?

I was horrified by it, of course.

Go on.

I was horrified because the expression on her face is one of apparent enjoyment. She seems to be relishing this moment, standing next to someone who appears to have died a violent death.

OK, do you think that she's responsible for his violent death?

One asks oneself that question. I didn't know for sure.

But isn't there the assumption? You see this . . .

Sure, you could look at it and assume, probably. I can't tell you what I thought at the time.

It's hard to remember what I thought when I first saw the photograph, because now I know so much more about it. I remember this argument that I had with one of my editors. We were editing that section on al-Jamadi, and he was saying to me, "How can you get past that smile? She's a monster." And I said, "I can get beyond it very easily." What are we looking at in this photograph? We're looking at a man who was murdered by the CIA, by a CIA officer who has never been charged with any wrongdoing in connection with this man's death. He was brought in by Navy Seals and CIA operatives early in the morning of Nov. 4, 2003. Within two and a half hours of his arrival at Abu Ghraib, he was dead. He walked in under his own power, and two and a half hours later he was dead. The various officers conspired to find a way to sneak the body out of the prison without anyone knowing that a murder had occurred. They wanted to pose him as a heart attack victim.

Sabrina had been told by her commanding officer that this man had died of a massive heart attack. Sabrina's father and her brother are cops. She herself wanted to be a forensic photographer. She went into the Army because she thought she would get money for an education and she could pursue this career. She and [Ivan] Frederick and [Charles] Graner got the extra key, stole into the shower room and took these pictures. Most people don't remember the pictures of the corpse, the forensic photographs that she took, over a dozen of them, showing the nature and extent of al-Jamadi's injuries. She was in no way involved with the coverup, she was in no way involved with the murder, she was lied to by her commanding officers and she imagined herself as exposing the military and the crime that occurred there by taking the photographs. The way I look at it is, under a different set of circumstances, she would be given a Pulitzer Prize in photography and not a year in military prison. And what is her crime? No one else was ever in prison in connection with al-Jamadi's death. What is her crime?

Exposing it.

Her crime is exposing a murder! It's actually even worse than that, her crime is embarrassing America, the administration and the military. The crime isn't murder! God forbid the crime should be murder. Now, here's your opportunity: You thought certain things about that photograph. I'd like you, right now, to apologize to me for having thought those things!

I apologize for having those thoughts cross my mind. I'm deeply sorry.

It's a deal.

"Standard Operating Procedure" opens April 25 in New York, Los Angeles and other major cities, with wider release to follow.

Shares