More than almost anyone in public life, Joe Lieberman knows from experience how to finesse a vice-presidential question. At the end of an impromptu press conference after a visit to discuss global warming with sixth graders here on Monday, Al Gore's 2000 veep pick was asked if he would be John McCain's running mate this time around. "No," Lieberman says flatly, as if the question were as ludicrous as his joining the antiwar movement. All Lieberman would add when prodded by a follow-up question is, "I think in this, as in so much else, [McCain] has his head screwed on right. I think he's looking for somebody who shares his priorities and would be capable of being president."

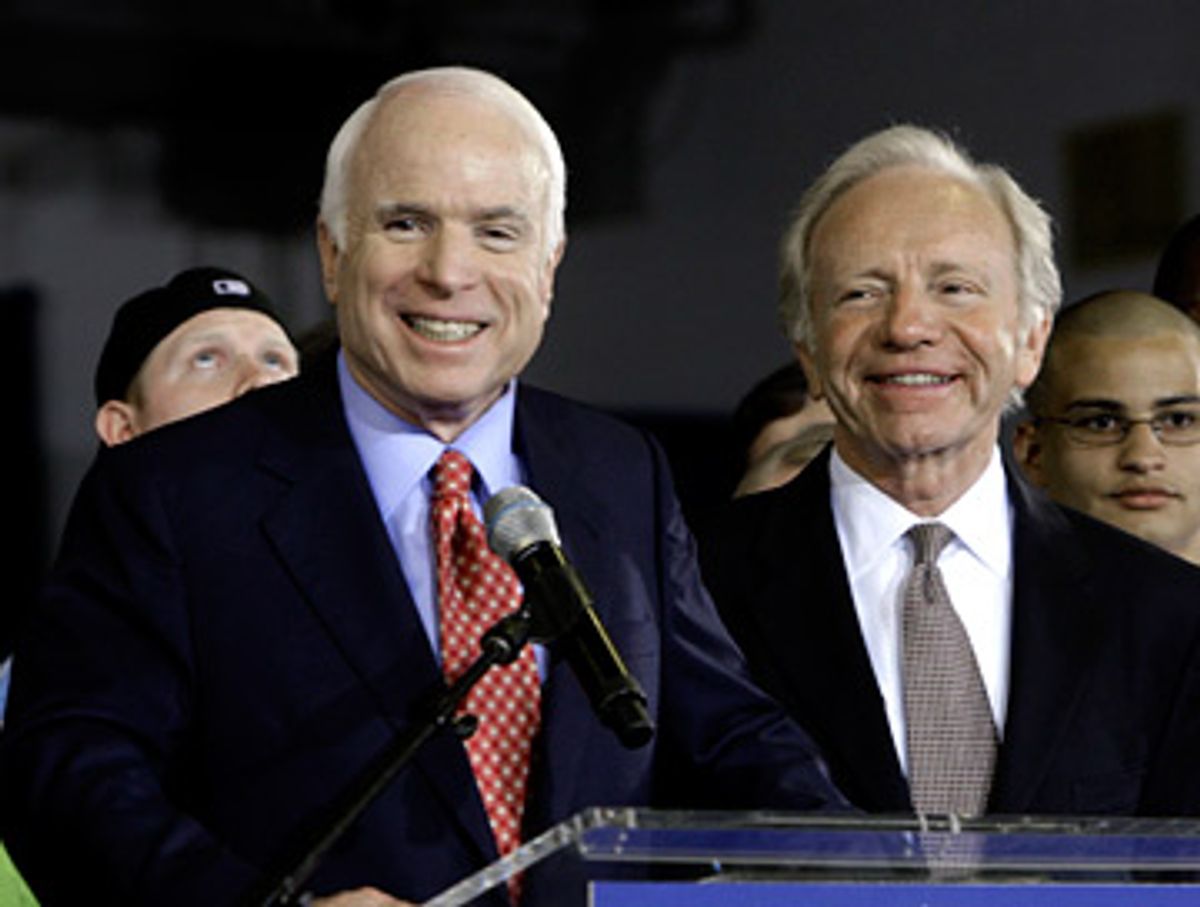

But in a presidential year filled with firsts (African-American nominee, serious woman candidate, former POW to be his party's standard-bearer), Lieberman retains the intriguing potential to become the first Jewish, party-crossing, second-time-around vice-presidential nominee in American history. While McCain is keeping his vice-presidential deliberations intensely private, it is not hard to pick up Republican whispers that the wild-card Lieberman speculation is grounded in reality rather than water-cooler fantasy. No McCain campaign sidekick -- not South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham nor former Hewlett Packard CEO Carly Fiorina -- does more than Lieberman to burnish the GOP candidate's reputation as a different-drummer Republican. As top McCain strategist Charlie Black says about Lieberman (talking in general, not as a potential running mate), "Joe, who is nationally known for having run for vice president and being elected [in 2006] as an independent, is the best possible character witness you can have for McCain's independence and bipartisan approach."

During an interview in his parked car in front of the Hillcrest Middle School, I asked Lieberman if his one-word press conference answer ("no") was a Shermanesque denial of willingness to be vice-president or merely a negative assessment of the odds of being asked. "It's all of that. I have done that," Lieberman says, not exactly taking himself out of the running. The 66-year-old Connecticut senator, who still identifies himself as an independent Democrat, adds, "I just think that John's got to go -- ought to go -- with a Republican because obviously it comes to the convention. I'm not a candidate. I don't think it's going to happen. And at this stage in my life, I am very happy where I am."

The key word in Lieberman's answer may well have been "convention." Because the big question is how the Republican delegates (especially the social conservatives who originally backed candidates like Mike Huckabee) would react to such an against-the-grain V.P. choice. Unyieldingly hawkish on Iraq and eager to work with Republicans in the Senate, Lieberman is reviled by Democratic activists as akin to another famous son of Connecticut -- Benedict Arnold. But in the context of the Republican Party, Lieberman suddenly becomes an ultra-liberal. Would the Republican base tolerate a pro-choice candidate like Lieberman for the heartbeat-away job, a senator who still caucuses with the Democrats and voted with them 81 percent of the time in 2007, according to Congressional Quarterly?

McCain has certainly grappled with this type of problem before. I remember him at his own book party at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York in the spring of 2004, when there was a flurry of talk that John Kerry might ask him to join the Democratic ticket, waving off questions about his intentions by saying in a puzzled tone, "I don't see how that would work." There is no tradition of bipartisanship in choosing a vice-president since the days when the Constitution gave the runner-up job to the second-place finisher in the Electoral College. That is why it is easy to envision angry antiabortion Republicans storming out of the convention in protest over a putative McCain-Lieberman ticket. But it is theoretically possible to imagine political benefits for McCain (who boasts a consistently antiabortion congressional voting record) in demonstrating his independence in his rejection of single-issue litmus-test politics.

Conservative Republican pollster John McLaughlin, who worked for Fred Thompson in the primaries, can see general-election political arguments for choosing Lieberman: "On one hand, it would be a sign than McCain was reaching out and broadening the party. And it would probably attract working-class conservative Democrats, the kind who voted for Hillary in the primaries." But McLaughlin can also picture the political downside: "On the other hand, if you look at Lieberman's record, it is pretty base Democratic, except on the war. And unless McCain has the Republican base in place, which he doesn't yet, he'd have a real problem with his own party." (McLaughlin, for his part, is far more intrigued with the veep potential of Virginia Rep. Eric Cantor, the only Jewish Republican in the House, who is a polling client.)

Lieberman is probably the most passionate advocate for the belief that McCain (despite reversing his position on the Bush tax cuts and speaking at Jerry Falwell's Liberty University) has not changed since the glory days of the 2000 primaries when the Arizona senator was lionized as a maverick Republican that even Democrats could love. As Lieberman put it during our interview, "I am convinced that a McCain administration would be very different from a Bush administration. The first difference is obvious -- the two people. John is such a unique person, so restless. He wants to get things done, he wants reform. As he says, he gets passionate about things. And I was thinking, we probably haven't had a president like McCain since Teddy Roosevelt."

The friendship between Lieberman and McCain pre-dates the Iraq war and harks back to Bill Clinton's second term when both senators on the Armed Services Committee were strong supporters of American intervention in Kosovo. Annual trips to a global security conference in Munich cemented the bonds. As Charlie Black puts it, "Joe's very close personally to McCain. They do compare notes about Iraq and other national-security issues on practically a daily basis. Joe's a close advisor as well as a campaigner."

A vice-presidential choice is often as much about personal chemistry as it is about ideology, geography or, well, political party. That is why, for all the political difficulties, Lieberman's name is apt to keep coming up as McCain mulls whom he wants to be standing next to him bathed in confetti at the GOP convention. It is a strange reality that the selection of Lieberman, who has become too conservative for most Democrats, would signal that McCain, after eight hard-right years of Bush, was truly trying to move the Republican Party toward the center.

Shares