"Is he still alive?" a friend asked me not long ago.

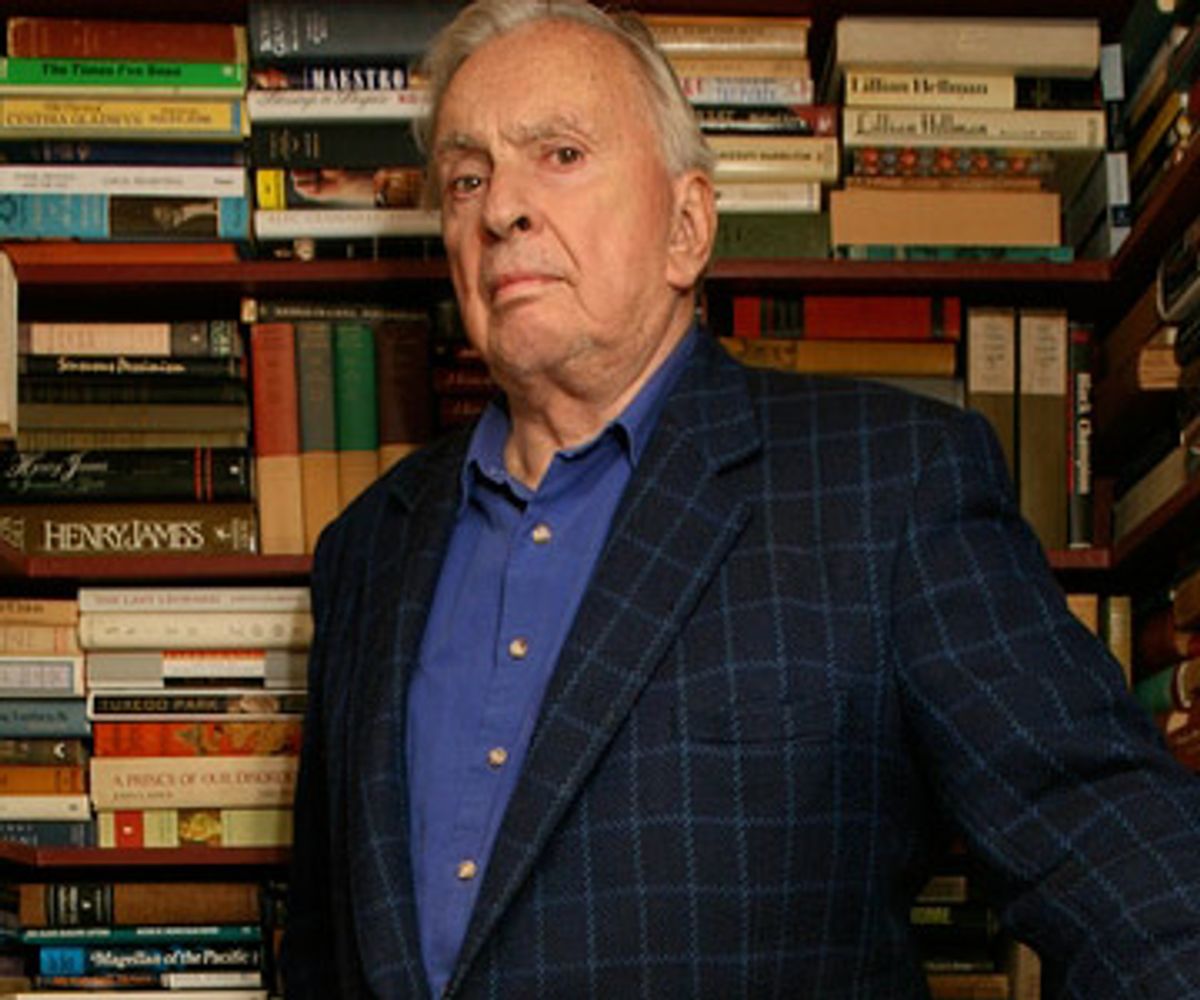

Casual observers might be excused for thinking of Gore Vidal in posthumous terms. A twilight pall suffused his most recent memoir, "Point-to-Point Navigation," which described the death of Vidal's longtime companion even as it ladled out retribution against longtime enemies. Many of those enemies have likewise passed on, and in recent appearances, Vidal has had to squeeze his proud, patrician figure into a wheelchair.

The old lion may be enfeebled, but he still has teeth. Doubters are referred to Deborah Solomon's recent New York Times Magazine interview, in which Vidal responded to the question "Were you chaste?" with a line that Groucho Marx might have coveted -- "Chased by whom?" -- and succinctly described his feelings on the death of William F. Buckley: "I thought hell is bound to be a livelier place, as he joins forever those whom he served in life, applauding their prejudices and fanning their hatred."

In the course of what must have been a terrifying conversation, Solomon managed to ask Vidal why critics prefer his essays to his novels. "That's because they don't know how to read," he replied. By now he has schooled us in the dangers of conventional wisdom, but in this case, the conventioneers have it right. Vidal has never produced a great novel (though not for want of trying) because he was, from the start, an essayist manqué.

It was his misfortune, perhaps, to come of age in postwar America, when the novel was still the royal road to glory. His first book, "Williwaw," was published when he was still 19. Several more followed, among them the succes de scandale of "The City and the Pillar," one of America's first fictional depictions of homosexuality (and barely readable today). But the field-clearing fame that the young Vidal clearly hungered for, the kind his rival Truman Capote snatched up right out of the gate -- all this eluded him.

Vidal would later blame his arrested development on the homophobia of mainstream review outlets, especially the New York Times. (To this day, the Gray Lady remains high on his shit list.) But he would also write, revealingly, of William Dean Howells, who, unable to get his poems published, "went off the deep end, into prose." Something similar happened to Vidal. Unable to claim his seat in Valhalla by fictional means, he came at it subterraneously -- through the literary journal -- brandishing not a sword but a quiver of aphorisms, smeared at the tips with invective.

Vidal, of course, would go on to write a great many more novels, most of them historical, a good many of them bestsellers. What he could never do was convince us that we were reading about someone other than Gore Vidal. "Burr," to cite one of his best works, was lively and rebarbative, and yet there was no way to reconcile its cynical, astringent protagonist with the quixotic historical figure who leapt from folly to folly. Burr was, of course, Vidal. As was Lincoln, as was Grant. As was Myra Breckinridge (though, in retrospect, she might better be described as Vidal's countercultural alter ego, which may explain why she is the most persuasive of his fictional personae).

Vidal's essays, by contrast, have all the strengths of his novels with this additional grace: They don't have to make a show of inhabiting other minds. And so the qualities of the originating mind -- wit, phrasemaking, autodidacticism, a talent to inflame -- stand out all the more starkly.

For proof, we may call up "The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal," assembled by Jay Parini, the author's literary executor (more whiffs of the posthumous). That word "selected," of course, implies a certain amount of cherry-picking. Juvenilia, senilia, outmoded usages, casual tribalisms have all presumably been cast away. Or have they? To Parini's credit, more than enough remains to show why and how Vidal gets under people's skin.

There is enough, too, to show that Vidal was, in some respects, well ahead of his time. His defense of homosexuality as "a matter of taste" (in the midst of the '60s), his calls for limits on executive power, his attack on "the National Security State" ... these still walk the razor's edge of topicality. Mere weeks after the Iraq war was joined, Vidal was calling attention to the prisoners in Guantánamo Bay. Some 15 years before Christopher Hitchens' "God Is Not Great," Vidal was declaring that monotheism was "the great unmentionable evil at the center of our culture."

He was not always so prescient. Taking his cues, probably, from Paul Ehrlich, he predicted that the entire planet would be overrun with famine by ... 2000. Some 28 years before that, he was declaring with great confidence that "the South is not about to support a party which is against federal spending ... Southern Democrats are not about to join with Nixon's true-blue Republicans in turning off federal aid."

But federal aid was the least of it. Southerners were breaking from the fold for cultural, not economic reasons, and American culture, in general, is one of Vidal's most notable blind spots. By his own choosing. Like Sinclair Lewis, he speaks of "our brainwashed majority," of the "hypocrisy and self-deception" that mark our "paradigmatic middle-class society." Unlike Lewis, he gives no signs of having actually lived there. The grandson of a U.S. senator, he was raised in privilege in Washington, D.C., and absconded as quickly as he could to Europe, sequestering himself for many years in a villa in Ravello, Italy, where he could get the right altitude on his native land.

But an aerial shot won't show you where all the bunkers are. No surprise, then, that wherever Vidal actually enters the bunker, his political reportage sparks to life. There's a deft analysis of Theodore Roosevelt that draws on conversations with Alice Longworth, and a wry and splendid take on his one-time pals the Kennedys ("The Holy Family," he calls them) that offers welcome ballast to the hagiographies of Schlesinger and Sorensen.

The old injunction to "write what you know" can be crippling for a writer of fiction, but for a writer of essays, it is close to an imperative. And there are clearly places Vidal hasn't been -- the corporate boardroom, for instance -- and things he doesn't know (though he doesn't always know it). His broad-brushed attacks on American power elites have earned him a reputation in many quarters for paranoia. In reality, he is simply vague (although vagueness is a prerequisite for paranoia). "The Few who control the Many through Opinion," he announces, "have simply made themselves invisible." A mercy for him, because he is excused from describing them at any length. He mutters darkly of "cash in white envelopes" and the "1 percent that owns the country" and the "elite" that is "really running the show." Beyond that level of signifying, he rarely ventures.

Which means that he can't exactly be proven right or wrong -- although history has done a fine job of vindicating him. If anything, the backroom corporate dealmaking of the current administration has shown that Vidal wasn't paranoid enough. We might venture to conclude, then, that he has been right more often than he has been wrong. The only problem is that he's often right for the wrong reasons. He disdains the U.S. power elite not because it oppresses the common man but because it savages his own vision of America, a history-steeped mythos that ignores (when it doesn't condemn) the multicultural realities of today's nation.

But if it's difficult to fix Vidal's standing as a political intellectual, there is no such difficulty in measuring his ability to read and assay literature. Indeed, the real contribution of Parini's collection is to remind us -- how exactly did we forget? -- that Vidal has been from the start one of our finest literary critics. Not simply because of those lancing quips. ("Might Updike not have allowed one blind noun to slip free of its seeing-eye adjective?" he wonders in a review of "In the Beauty of the Lilies.") But because the act of reading other people's books frees Vidal from having to swallow all the oxygen in the room. In much of his political writing, knowingness passes for knowledge. Here, that tends to fall away, and what's left is a man genuinely engaged with the matter at hand and willing to be changed by it.

In his long analysis of the French New Novelists, for example, Vidal cogently makes the case for theoreticians like Alain Robbe-Grillet and Nathalie Sarraute before parting ways, reluctantly but firmly. "There is something old-fashioned and touching," he writes, "in [the] assumption ... that if only we all try hard enough in a 'really serious' way, we can come up with the better novel. This attitude reflects not so much the spirit of art as it does that of Detroit."

"The French mind," he adds, "is addicted to the postulating of elaborate systems in order to explain everything, while the Anglo-American mind tends to shy away from unified-field theories. We chart our courses point to point; they sight from the stars. The fact that neither really gets much of anywhere doesn't mean that we haven't all had some nice outings over the years."

There is a refreshing lack of doctrine in that judgment, and Vidal's strength as a critic is that he refuses to matriculate into anyone's school. An exhaustive study of the "Art Novels" of Barth, Barthelme and Gass leads him back to his first conclusion: "I find it hard to take seriously the novel that is written to be taught." But the road that leads him there is cobbled with dazzling insights. "I suspect that the energy expended in reading 'Gravity's Rainbow' is, for anyone, rather greater than that expended by Pynchon in the actual writing. This is entropy with a vengeance. The writer's text is ablaze with the heat/energy that his readers have lost to him."

With other authors, Vidal can be quite startlingly generous. I was surprised to learn that he considers Thornton Wilder "one of the few first-rate writers the United States has produced." Kudos are likewise extended to Italo Calvino and to Edgar Rice Burroughs (a boyhood favorite). Vidal almost single-handedly salvaged the fortunes of the late Dawn Powell, who, in his perfect formulation, "hammered on the comic mask and wore it to the end."

Vidal even has a grudging word or two for smut merchants. "By their nature," he writes, "pornographies cannot be said to proselytize, since they are written for the already hooked. The worst that can be said of pornography is that it leads not to 'antisocial' sexual acts but to the reading of more pornography. As for corruption, the only immediate victim is English prose."

On at least one occasion, as I recall, Vidal has confessed that his primary passion in life is not writing but reading, and judging from these deeply informed essays, I can well believe it. Others may suspect him of less pure motives. His social circle has been notable for its glamour, and his willingness to grant audiences to every reporter who comes calling has passed well beyond compulsion. Interviews, in general, bring out his very worst grandstanding impulses and goad him into his most insupportable statements (a bizarre defense of Timothy McVeigh, for instance, and the usual cockamamie theorizing about 9/11).

Vidal's well-documented reputation as a go-to provocateur has made it all too easy to overlook his astonishing work ethic: 24 novels, five plays, two memoirs, screenplays, television dramas, short stories, pamphlets and more than 200 essays. As this particular collection makes clear, Vidal writes to live. Approvingly, he recalls the final days of Edmund Wilson: "He was perfect proof of the proposition that the more the mind is used and fed the less apt it is to devour itself. When he died, at seventy-seven, he was busy stuffing his head with irregular Hungarian verbs. Plainly, he had a brain to match his liver."

Plainly, too, Vidal has a brain to match his self-regard. And late at night, when the blandishments of ego subside and a new book lies open in his lap, his lifelong, half-requited love for the novel still burns bright -- no matter that the novel itself is fading into insignificance. "Our lovely vulgar and most human art is at an end," he wrote in 1967, "if not the end. Yet that is no reason not to want to practice it, or even to read it. In any case, rather like priests who have forgotten the meaning of the prayers they chant, we shall go on for quite a long time talking of books and writing books, pretending all the while not to notice that the church is empty and the parishioners have gone elsewhere to attend other gods, perhaps in silence or with new words."

Shares