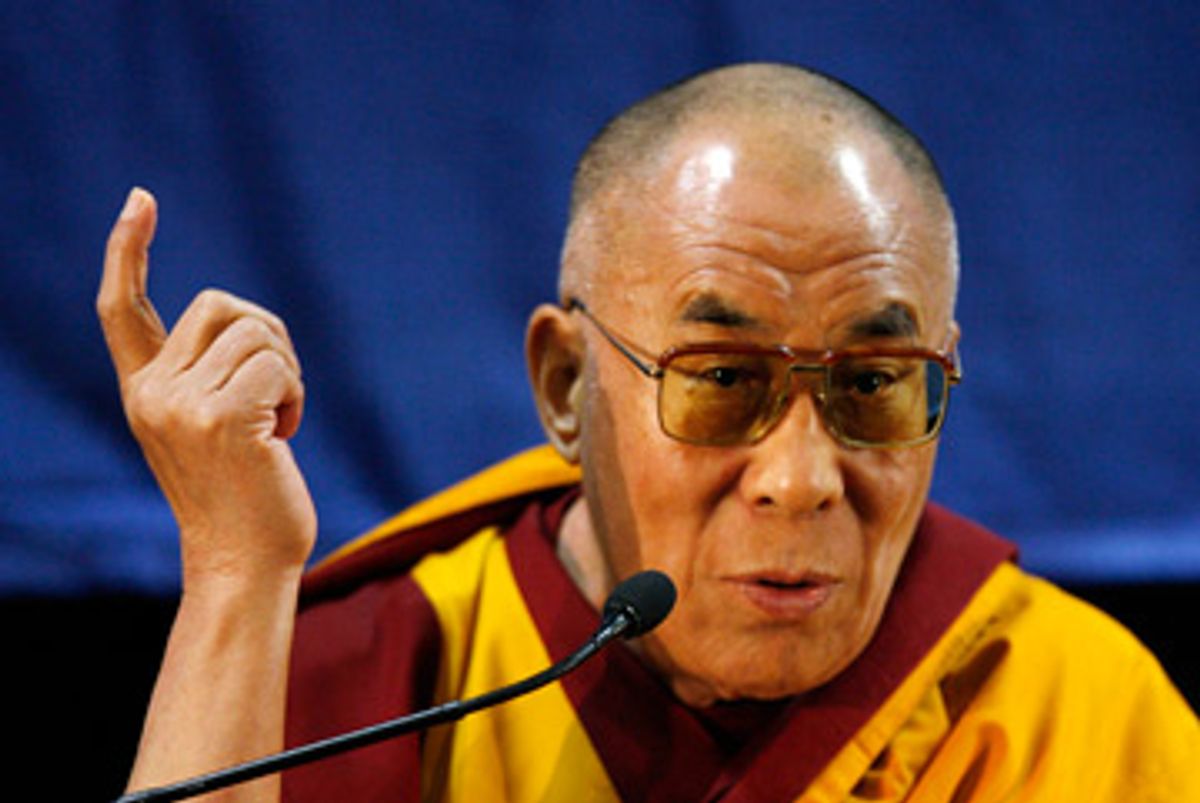

It takes a particular form of confidence to sit across a negotiating table, armed only with moral courage and wearing religious robes, facing representatives of one of the world's biggest armies and one of the five official nuclear powers in the world. That's just what is happening this week, as representatives of the Dalai Lama -- whom the Chinese continue to call "the splittist monk," or, as in an official commentary in the New China News Agency yesterday, "a flunky" – went to Beijing, ignoring the insults and instead praising reports that nearly 1,000 Tibetans have been released from Chinese jails.

The Dalai Lama has not had it easy. This is the year of the Olympics in Beijing, which many supporters of China would like to take place unchallenged. The run of the Olympic torch earlier this summer was marred by protests in Western capitals that pitted pro-Tibet activists, some of whom are resisting the Dalai Lama's nonviolent convictions, against fiercely nationalist Chinese students and residents. The Dalai Lama found that government officials in several Western countries historically sympathetic to the Tibetan cause were curiously unavailable this year; even in Germany, where Chancellor Angela Merkel has been vocal in condemning China's human rights record, this year the Dalai Lama could only meet junior officials.

At one level, the struggle for Tibet's autonomy has become symbolic: Tibetan independence appears impossible, and while awareness about the cause has risen, nobody wants to do anything about it for fear of offending China. Meanwhile, writing in the New York Times last month, Nicholas Kristoff mentions two Tibetan monks, released recently from Chinese prisons, where they have been beaten. Their patience is wearing thin. Till when can we continue to remain nonviolent, they ask Kristoff.

Those monks are not alone. Younger Tibetans are increasingly frustrated, as they can't see any light at the end of the tunnel. Jamyang Norbu, an acclaimed Tibetan writer in exile, believes the Dalai Lama's approach is too conciliatory; the cause, he says, has now been fossilized in its own myths.

Keeping the idea of Tibet alive is a formidable challenge. First, there is the rise of China. Second, the perceived strategic insignificance of Tibet. And third, what Tibetan activists call China's cultural genocide in Tibet, as Han Chinese are making Tibetans a minority in their own land. Since the Chinese influx, Tibetan culture has been desecrated by the opening of karaoke bars and brothels near monasteries and the building of in-your-face retail centers opposite the Potala Palace. Many Tibetans have grown up with only a dim recollection of the Dalai Lama and a limited awareness of their faith and traditions.

During the recent uprisings, some Tibetan activists have turned violent in the face of Chinese provocation. Has nonviolence had its day?

It would be a great tragedy if the Tibetan movement were to cast aside its nonviolent activism, passive resistance, or civil disobedience because violence seems more expedient. The pursuit of nonviolence gives the Tibetan movement its moral appeal. And there is no reason to believe that a violent uprising will succeed. If Tibetans turn violent, they will have given up their moral appeal. Violence, after all, has not given Palestinians the freedom they have sought, either.

Indeed, of all the world leaders in major struggles of national identity today, the Dalai Lama comes closest to following the model associated with Gandhi, who was assassinated 60 years ago this year. The key difference between them is that Gandhi fought a colonial power, Britain, which was democratic at home. Tibet's oppressors aren't. Does this mean nonviolence has only limited appeal and that it can work only in certain contexts?

At one level, the Indian struggle does seem like an exception. Gandhi used his training as a barrister from London to argue to the British that their rule was unjust and illegal. And the British agreed and left. But it was never that simple: Gandhi's struggle lasted a full three decades, and during that period, the British often responded with force, and at other times with cunning, subterfuge, and divisive politics. They left in 1947 when they found that sustaining the empire was no longer possible economically, politically, or morally.

And the Dalai Lama's struggle is not the only such: Even after the Prague Spring faded, the playwright Vaclav Havel insisted that he'd live the truth, not lies that the Soviet-backed Czechoslovak government imposed. Like Gandhi, Havel was jailed, but he never gave up. His patience and stubbornness were rewarded: Two decades later, Havel became the Czech Republic's president. Democracies, even flawed ones, understand this moral force: That's why Israel expelled the nonviolent activist Mubarak Awad in the 1980s; now, Sari Nusseibeh is giving Gandhian tactics another chance in the Middle East.

Violence always appears more expedient in the short run. But the whole point of nonviolence is the choice of certain means over others to attain particular ends. In February 1922, Indian activists were marching through a small town called Chauri Chaura in northern India, ostensibly part of Satyagraha, the nonviolent movement Gandhi founded. They ran into a group of policemen. The activists shouted slogans; the police beat them up. Just then, a larger group of activists arrived and chased the policemen, who ran to the local police station. The activists locked the police station from outside and burned the building, killing over 20 policemen.

It was an isolated incident, and Gandhi could have viewed it as such. But he termed the incident "a divine warning" and decided that tempers had to cool. He would not surrender the moral authority he sought to base, violent instincts; Gandhi knew what violence begat: more violence. In one of the more memorable statements attributed to him, Gandhi said: "An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind." Against the advice of his senior allies, he suspended the movement.

That's the answer to what the Dalai Lama should do if the Tibetan uprising turns violent – suspend the movement. He can do so, because his sense of "time" differs from that of leaders in business and politics. Corporations think of the next quarter. Politicians in a democratic society think of the next election. Communists think a generation ahead. But in the Dalai Lama they have a unique rival. If he has to, he is prepared to wait for his next incarnation in order not to surrender his moral authority.

Can the suffering of his followers wait that long, though? Some are losing patience; some want freedom in this world, not from the world. Can the Dalai Lama keep them calm even as he tries to shame the Chinese into doing the right thing?

Overwhelming evidence seems to suggest not. This week's talks are unlikely to yield much, if any, progress, and could push more Tibetans to the boiling point. But listen to Gandhi again: "When I despair, I remember that all through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants and murderers and for a time they seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall -- think of it, always."

Shares