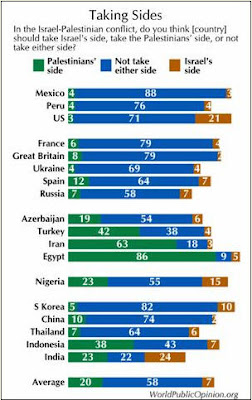

One of the most striking aspects of our political discourse, particularly during election time, is how efficiently certain views that deviate from the elite consensus are banished from sight -- simply prohibited -- even when those views are held by the vast majority of citizens. The University of Maryland's Program on International Policy Attitudes -- the premiere organization for surveying international public opinion -- released a new survey a couple of weeks ago regarding public opinion on the Israel-Palestinian conflict, including opinion among American citizens, and this is what it found:

A new WorldPublicOpinion.org poll of 18 countries finds that in 14 of them people mostly say their government should not take sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Just three countries favor taking the Palestinian side (Egypt, Iran, and Turkey) and one is divided (India). No country favors taking Israel's side, including the United States, where 71 percent favor taking neither side.

The worldwide consensus is crystal clear -- citizens want their Governments to be neutral and even-handed in the Israel-Palestinian conflict, not tilted towards either side. And that consensus is shared not just by a majority of American citizens, but by the overwhelming majority. Few political views, particularly on controversial issues, attract more than 70% support among American citizens. But the proposition that the U.S. Government should be even-handed -- rather than tilting towards Israel -- attracts that much support. That's not an "anti-Israeli" view -- to the contrary, it's a position that America can and should resolve that violent, four-decades-long dispute by being even-handed rather than one-sided.

And that consensus is shared not just by a majority of American citizens, but by the overwhelming majority. Few political views, particularly on controversial issues, attract more than 70% support among American citizens. But the proposition that the U.S. Government should be even-handed -- rather than tilting towards Israel -- attracts that much support. That's not an "anti-Israeli" view -- to the contrary, it's a position that America can and should resolve that violent, four-decades-long dispute by being even-handed rather than one-sided.

Similarly, when asked "How well do you think Israel is doing its part in the effort to resolve the Israel-Palestinian conflict," citizens around the world, by a large margin, believe that Israel is doing either "not very well" or "not well at all" (54% -- compared to 23% that say it's doing "very well" or "somewhat well"). And there, too, that worldwide view corresponds to American public opinion as well. 59% of Americans say Israel is doing either "not very well" or "not well at all" -- compared to only 30% that say it's doing "very well" or "somewhat well." And Palestinians don't fare much better worldwide (38-49%) and fare worse in the U.S. (15-75%).

Yet not only is the view of "even-handedness" completely unrepresented among mainstream political figures in the U.S., it's deemed political death to go anywhere near expressing that view. Back in 2003, then-presidential-candidate Howard Dean expressed the exact position favored by an overwhelming majority of Americans, yet triggered an intense and even ugly controversy by doing so:

Dean's Israel troubles began at a Sept. 3 campaign event in Santa Fe, N.M. When it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he said that day, "It's not our place to take sides." Then, on Sept. 9, he told the Washington Post that America should be "evenhanded" in its approach to the region.

That's all Dean said. It's a view held by more than 70% of Americans. It ought to be completely uncontroversial -- if anything, it ought to be that view that is deemed a political piety. But what happened? This, according to an excellent account of that "controversy" in Salon by Michelle Goldberg:

The media and the Democratic establishment reacted as if Dean had called Yasser Arafat a man of peace. On Sept. 10, 34 Democratic members of Congress, including House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, wrote Dean an open letter. "American foreign policy has been -- and must continue to be -- based on unequivocal support for Israel's right to exist and to be free from terror . . ." they wrote. "It is unacceptable for the U.S. to be 'evenhanded' on these fundamental issues . . . This is not a time to be sending mixed messages; on the contrary, in these difficult times we must reaffirm our unyielding commitment to Israel's survival and raise our voices against all forms of terrorism and incitement."The Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz reported that Dean had badly damaged his own campaign. "Sources in the Jewish community say that Dean has wrecked his chances of getting significant contributions from Jews . . ." the paper wrote. "Many believe Dean's statement will drive more Jews toward Lieberman and Kerry, enabling Kerry to take the lead again."

Dean was roundly attacked by the political elite for uttering "anti-Israel" comments, notwithstanding the fact that Dean is married to a Jewish woman, raised his children as Jews, and, most amazingly of all, had a campaign that was managed by Steve Grossman, a former President of AIPAC. But no matter: Dean had uttered a Forbidden Thought -- forbidden even though it is embraced by the vast majority of Americans -- and thus Grossman and Dean had to subject themselves to abject Apology Rituals:

According to the Dean campaign, the uproar involved semantics, not substance. "Here's what I think happened," says Grossman, Dean's campaign co-chair. "Howard made some comments in someone's backyard in New Mexico that were shorthand, if you will, for some of his Middle East views. In the course of those remarks and some others in the subsequent days, he used some language that gave people consternation, and it was immediately jumped on by Joe Lieberman and John Kerry that somehow Howard Dean was breaking faith with this 55-year tradition of the United States' special relationship with Israel, which is patently absurd". . . .If Dean's Israel position really puts him far out on the left, it proves that not showing unequivocal support for the Jewish state remains a political poison pill -- for members of either political party. . . .

After all, according to Grossman, the candidate remains in sync with the goals of Bush's Israel policy. . . . No serious candidate took a position to the left of Bush. Indeed, it's precisely because there's no real leftist alternative that Dean's been cast in that role. . . . . But a campaign is always more about images and impressions than carefully formulated positions, and that's where Dean has blundered.

It was conventional wisdom that that Dean had committed some grave mistake even though, as The Nation's John Nichols highlighted at the time, Dean was expressing the overwhelming majority view even back in 2003:

More troubling is the condemnation by Pelosi and other party leaders of even a hint of "evenhandedness." That smacks of the old game of positioning Democrats to the right of the Republicans on Middle East policy -- in a perceived contest for Jewish-American votes and contributions. The problem with this approach, as Middle East scholar Stephen Zunes points out, is that "this suggests you cannot be firmly committed to Israel and question [Israel's hawkish Prime Minister] Ariel Sharon's policies. If that's where Democrats put themselves, they don't leave room to debate Bush on the issue." They'll also have a tougher time appealing to American voters -- 73 percent of whom, according to a recent University of Maryland poll, prefer that the United States not take sides.

It's pretty extraordinary that in a democracy, the political elite is able to render completely off-limits a view that the vast majority of Americans support. They actually render majority-held views unspeakable and then remove the issue entirely from what is debated. No matter what one's views are, there is no denying that our policy towards Israel is immensely consequential for our country. Yet, by virtue of the fact that presidential candidates are required to affirm essentially the same orthodoxies, there's very little difference in their positions towards Israel and therefore our current policy approach towards Israel will simply not be part of anything that is debated, even though most Americans overwhelmingly oppose that course.

Indeed, as soon as he secured the Democratic nomination, Barack Obama made a pilgrimage to AIPAC in order to avoid the "Howard Dean mistake" and to vow that there would be no such debate over Israel in this election:

I have been proud to be a part of a strong, bi-partisan consensus that has stood by Israel in the face of all threats. That is a commitment that both John McCain and I share, because support for Israel in this country goes beyond party. . . .And then there are those who would lay all of the problems of the Middle East at the doorstep of Israel and its supporters, as if the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the root of all trouble in the region. These voices blame the Middle East's only democracy for the region's extremism. They offer the false promise that abandoning a stalwart ally is somehow the path to strength. It is not, it never has been, and it never will be.

Our alliance is based on shared interests and shared values. Those who threaten Israel threaten us. Israel has always faced these threats on the front lines. And I will bring to the White House an unshakeable commitment to Israel's security.

That starts with ensuring Israel's qualitative military advantage. I will ensure that Israel can defend itself from any threat -- from Gaza to Tehran. Defense cooperation between the United States and Israel is a model of success, and must be deepened. As President, I will implement a Memorandum of Understanding that provides $30 billion in assistance to Israel over the next decade -- investments to Israel's security that will not be tied to any other nation.

In fairness, Obama did attack what he called the "failed status quo"; disputed that "America's recent foreign policy has made Israel more secure"; and pointed to "eight years of accumulated evidence that our foreign policy is dangerously flawed." Moreover, Obama -- to his great credit -- spent the primary season making some important and unorthodox points about Palestinian suffering and pointing out that the President should not be blindly supportive of everything Israel's right-wing does, that being "pro-Israel" doesn't mean a refusal to oppose Israeli actions.

But by uttering such Forbidden (though quite mainstream) thoughts, Obama was mercilessly attacked as anti-Israel and even anti-Semitic, and with the nomination secured, the crux of his June AIPAC speech was an affirmation of our political establishment's mandated Israel orthodoxy: the continuation of America's one-sided alliance with Israel, as highlighted by commitments such as this:

Finally, let there be no doubt: I will always keep the threat of military action on the table to defend our security and our ally Israel. Sometimes there are no alternatives to confrontation. . . . That is the change we need in our foreign policy. Change that restores American power and influence. Change accompanied by a pledge that I will make known to allies and adversaries alike: that America maintains an unwavering friendship with Israel, and an unshakeable commitment to its security. . . .As members of AIPAC, you have helped advance this bipartisan consensus to support and defend our ally Israel. And I am sure that today on Capitol Hill you will be meeting with members of Congress and spreading the word. But we are here because of more than policy. We are here because the values we hold dear are deeply embedded in the story of Israel.

Again, the point has nothing to do with one's views of the best policy towards Israel. The point is that a position which the vast majority of Americans embrace is one that, simultaneously, is forbidden to be expressed, and the election consequently will involve no debate over that issue.

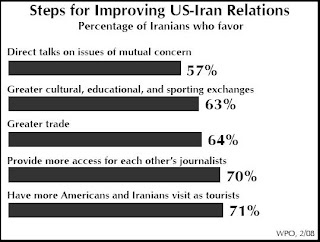

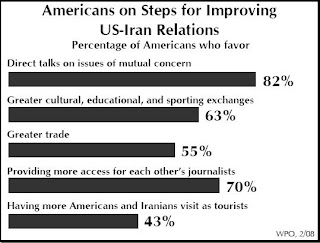

That profoundly anti-democratic dynamic is by no means confined to Israel. That's just an example. A different University of Maryland poll was released in April of this year, which surveyed public opinion in Iran and the U.S. regarding the disputes between those two countries. The populations of both countries have strikingly similar views with regard to those matters, with large majorities favoring the same deal to resolve the dispute (Iran has the right to develop nuclear energy accompanied by IAEA inspections to prevent weaponization), and large majorities also favor the NPT's goal of "eliminating all nuclear weapons." More strikingly, the citizens of both countries overwhelmingly favor the same policies of rapproachment and cooperation, rather than the bluster, threats, and ongoing provocative acts engaged in by both of their governments:

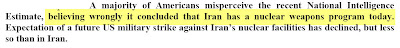

Remarkably, this desire for cooperation rather than confrontation is the view of most Americans despite the Iraq-level misinformation and propaganda which our political elite has disseminated about Iran:

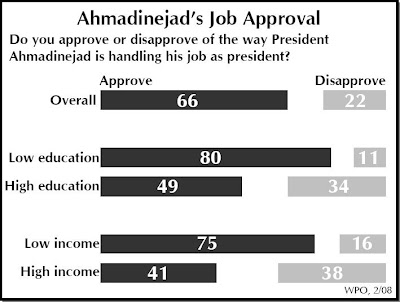

And while Iranian President Ahmadinejad is depicted by our political class as the Equivalent of Adolf Hitler, savagely oppressing Iranians as some sort of insane, vicious tyrant, that isn't how they see it:

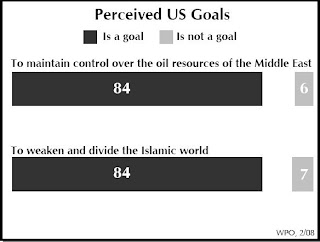

Iranian public opinion distinguishes between the U.S. Government and the American people -- holding favorable views towards the latter and unfavorable views towards the former ("some portrayed the American people, like the Muslim people, as victims of the American government") -- and to the extent there is "anti-Americanism" in Iran, it is based on this widespread assessment:

That, too, is a belief widely held in many places in the world, yet is one that no mainstream politician in the U.S. could express.

There are all sorts of reasons why our presidential elections center on personality-based sideshows (even Washington Post ombudsman Deborah Howell said as much about her own paper's coverage today). Those gossipy matters are easier for our slothful, vapid media stars to digest and spout. They require very few resources to cover. The campaign consultants who run national political campaigns are experts in P.R. strategies for packaging personalities and indifferent to policy debates, etc. etc.

But one principal reason is that so many of the Government's most consequential actions are concealed behind a wall of secrecy and thus not subject to public debate. Meanwhile, those policies which are publicly disclosed are kept off-limits from any real debate and, even when they are debated, public opinion is almost completely marginalized in favor of the minority elite consensus (see, for instance, the endless Iraq war even in the face of long-standing, overwhelming support for its end).

That remarkable dynamic of debate-suppression is most conspicuous -- and most urgent -- when the policies favored by the political establishment are ones that are vigorously rejected by the citizenry. Thus we have the extraordinary fact that a policy that has long been favored by the vast majority of Americans -- even-handedness in the Israel-Palestinian conflict -- is one that no mainstream American politician of any national significance can espouse without triggering an immediate end to their political career. That discrepancy is a rather potent commentary on how our democracy functions.

Shares