A minute past midnight on Aug. 2, bookstores across the country will for the first time repeat a ritual once reserved for a single author: J.K. Rowling. They'll stay open late and begin selling copies of "Breaking Dawn" by Stephenie Meyer, the fourth novel of the Twilight series, at the first moment they're officially permitted to do so. Tens of thousands of fans plan to congregate for these release parties, message boards have shut down to guard against leaked spoilers, and as many as a million readers will be blocking out an entire weekend to bury themselves in the book.

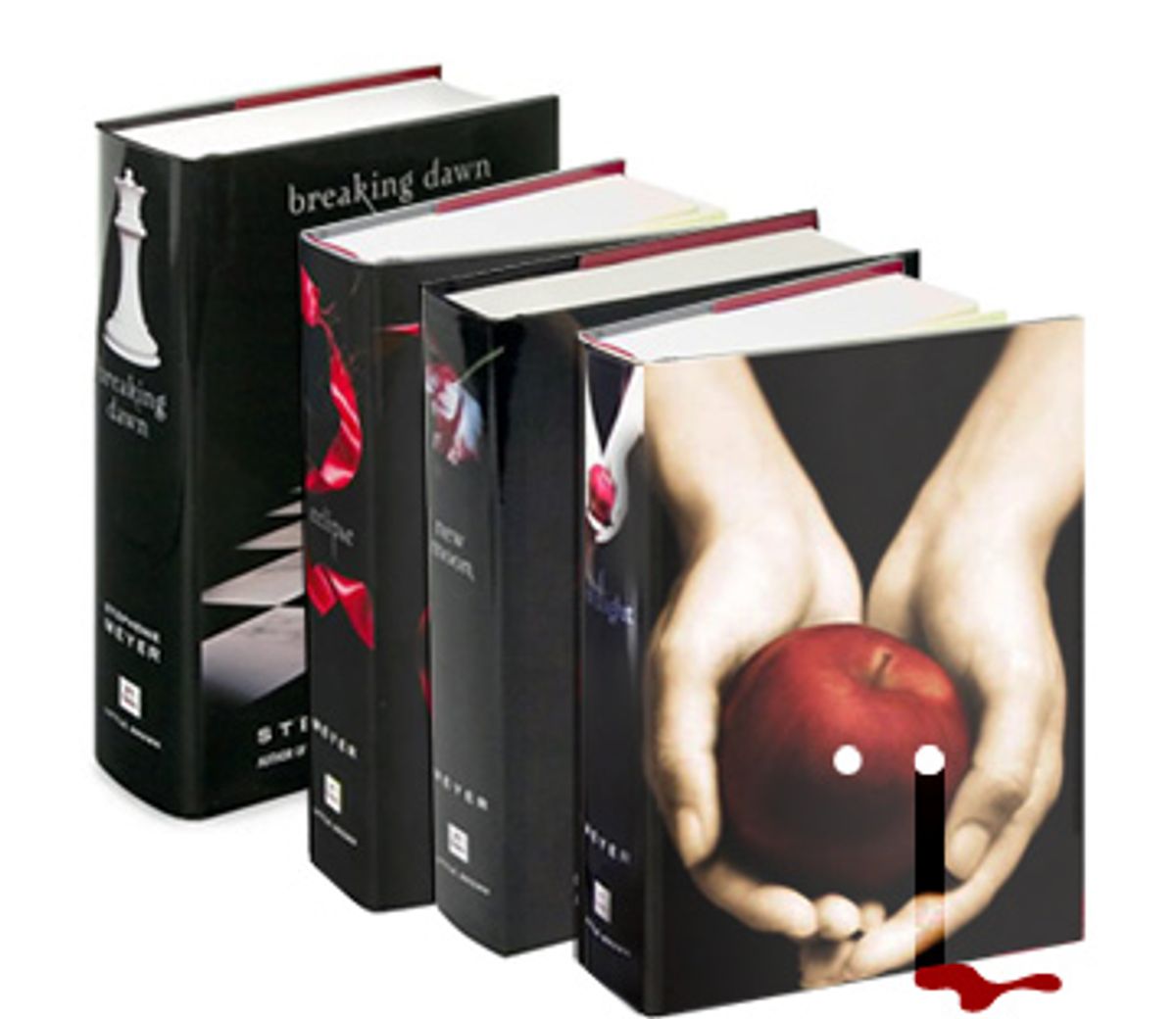

The preceding three installments in the series -- "Twilight," "New Moon" and "Eclipse" -- occupy the top slots in Publishers Weekly's bestseller list for children's fiction (they are categorized as Young Adult, or YA, titles), and are among the top five overall bestsellers on USA Today's list. In May, Publishers Weekly reported that 5.3 million copies of the Twilight books had sold in the U.S. alone. When a movie based on the first novel comes out in December, expect to see book sales jump to numbers that approach Rowling's eight-figure numbers.

No wonder the media has heralded Twilight as the next Harry Potter and Meyer as the second coming of J.K. The similarities, however, are largely commercial. It's hard to see how Twilight could ever approach Harry Potter as a cultural phenomenon for one simple reason: the series' fan base is almost exclusively female. The gender imbalance is so pronounced that Kaleb Nation, an enterprising 19-year-old radio show host-cum-author, has launched a blog called Twilight Guy, chronicling his experiences reading the books. The project is marked by a spirit that's equal parts self-promotion and scientific inquiry -- "I am trying to find why nearly every girl in the world is obsessed with the Twilight books by Stephenie Meyer" -- and its premise relies on the fact that, in even attempting this experiment, Nation has made himself an exceptional guy indeed.

Bookstores have been known to shelve the Twilight books in both the children's and the science fiction/fantasy sections, but they are -- in essence and most particulars -- romance novels, and despite their gothic trappings represent a resurrection of the most old-fashioned incarnation of the genre. They summon a world in which love is passionate, yet (relatively) chaste, girls need be nothing more than fetchingly vulnerable, and masterful men can be depended upon to protect and worship them for it.

The series' heroine, Bella Swan, a 16-year-old with divorced parents, goes to live with her father in the small town of Forks, Wash. (a real place, and now a destination for fans). At school, she observes four members of a fabulously good-looking and wealthy but standoffish family, the Cullens; later she finds herself seated next to Edward Cullen in biology lab and is rendered nearly speechless by his spectacular beauty. At first, he appears to loathe her, but after a protracted period of bewilderment and dithering she discovers the truth. Edward and his clan are vampires who have committed themselves to sparing human life; they call themselves "vegetarians." The scent of Bella's blood is excruciatingly appetizing to Edward, testing his ethical limits and eventually his emotional ones, too. The pair fall in love, and the three books detail the ups and downs of this interspecies romance, which is complicated by Bella's friendship with Jacob Black, a member of a pack of Native American werewolves who are the sworn enemies of all vampires.

Comparisons to another famous human girl with a vampire boyfriend are inevitable, but Bella Swan is no Buffy Summers. "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" was at heart one of those mythic hero's journeys so beloved by Joseph Campbell-quoting screenwriters, albeit transfigured into something sharp and funny by making the hero a contemporary teenage girl. Buffy wrestled with a series of romantic dilemmas -- in particular a penchant for hunky vampires -- but her story always belonged to her. Fulfilling her responsibilities as a slayer, loyalty to her friends and family, doing the right thing and cobbling together some semblance of a healthy life were all ultimately as important, if not more important, to her than getting the guy. If Harry Potter has a vampire-loving, adolescent female counterpart, it's Buffy Summers.

By contrast, Bella, once smitten by Edward, lives only for him. When he leaves her (for her own good) at the beginning of "New Moon," she becomes so disconsolate that she resorts to risking her own life, seeking extreme situations that cause her to hallucinate his voice. This practice culminates in a quasi-suicidal high dive into the ocean, after which, on the brink of drowning, she savors visions of her undead boyfriend: "I thought briefly of the clichés, about how you're supposed to see your life flash before your eyes. I was so much luckier. Who wanted to see a rerun, anyway? I saw him, and I had no will to fight ... Why would I fight when I was so happy where I was?" After Edward returns, the only obstacle she can see to her eternal happiness as a member of the glamorous Cullen family is his stubborn refusal to turn her into a vampire: He's worried that she'll lose her soul.

Otherwise directionless and unsure of herself, Bella's only distinguishing trait is her clumsiness, about which she makes frequent self-deprecating jokes. But Bella is not really the point of the Twilight series; she's more of a place holder than a character. She is purposely made as featureless and ordinary as possible in order to render her a vacant, flexible skin into which the reader can insert herself and thereby vicariously enjoy Edward's chilly charms. (His body is as hard and cold as stone, an ick-inducing detail that this reader, for one, found impossible to get past.) Edward, not Bella, is the key to the Twilight franchise, the thing that fans talk about when explaining their fascination with the books. "Perfect" is the word most often used to describe him; besides looking like a male model, Edward plays and composes classical music, has two degrees from Harvard and drives several hot cars very, very fast. And he can read minds (except, mysteriously, for Bella's). "You're good at everything," Bella sighs dreamily.

Even the most timorous teenage girl couldn't conceive of Bella as intimidating; it's hard to imagine a person more insecure, or a situation better set up to magnify her insecurities. Bella's vampire and werewolf friends are all fantastically strong and fierce as well as nearly indestructible, and she spends the better part of every novel alternately cowering in their protective arms or groveling before their magnificence. "How well I knew that I wasn't good enough for him" is a typical musing on her part. Despite Edward's many protestations and demonstrations of his utter devotion, she persists in believing that he doesn't mean it, and will soon tire of her. In a way, the two are ideally suited to each other: Her insipidity is the counterpart to his flawlessness. Neither of them has much personality to speak of.

But to say this is to criticize fantasy according to the standards of literature, and Meyer -- a Mormon housewife and mother of three -- has always been frank about the origins of her novels in her own dreams. Even to a reader not especially susceptible to its particular scenario, Twilight succeeds at communicating the obsessive, narcotic interiority of all intense fantasy lives. Some imaginary worlds multiply, spinning themselves out into ever more elaborate constructs. Twilight retracts; it finds its voluptuousness in the hypnotic reduction of its attention to a single point: the experience of being loved by Edward Cullen.

Bella and her world are barely sketched -- even Edward himself lacks dimension. His inner life and thoughts are known to us only through what Bella sees him say or do. The characters, such as they are, are stripped down to a minimum, lacking the texture and idiosyncrasies of actual people. What this sloughing off permits is the return, again and again, to the delight of marveling at Edward's beauty, being cherished in his impermeable arms, thrilling to his caresses and, above all, hearing him profess, over and over, his absolute, unfailing, exclusive, eternal and worshipful adoration. A tiny sample:

"Bella, I couldn't live with myself if I ever hurt you. You don't know how it's tortured me ... you are the most important thing to me now. The most important thing to me ever."

"I could see it in your eyes, that you honestly believed that I didn't want you anymore. The most absurd, ridiculous concept -- as if there were any way that I could exist without needing you!"

"For this one night, could we try to forget everything besides just you and me?" He pleaded, unleashing the full force of his eyes on me. "It seems like I can never get enough time like that. I need to be with you. Just you."

Need I add that such statements rarely issue from the lips of mortal men, except perhaps when they're looking for sex? Edward, however, doesn't even insist on that -- in fact, he refuses to consummate his love for Bella because he's afraid he might accidentally harm her. "If I was too hasty," he says, "if for one second I wasn't paying enough attention, I could reach out, meaning to touch your face, and crush your skull by mistake. You don't realize how incredibly breakable you are. I can never, never afford to lose any kind of control when I'm with you." As a result, their time together is spent in protracted courtship: make-out sessions and sweet nothings galore, every shy girl's dream.

Yet it's not only shy girls who crush mightily on Edward Cullen. One of the series' most avid fan sites is Twilight Moms, created by and for grown women, many with families of their own. There, as in other forums, readers describe the effects of Meyer's books using words like "obsession" and "addiction." Chores, husbands and children go neglected, and the hours that aren't spent reading and rereading the three novels are squandered on forums and fan fiction. "I have no desires to be part of the real world right now," posted one woman. "Nothing I was doing before holds any interest to me. I do what I have to do, what I need to do to get by and that's it. Someone please tell me it will ease up, even if just a little? My entire world is consumed and in a tailspin."

The likeness to drug addiction is striking, especially when you consider that literary vampirism has often served as a metaphor for that form of enthrallment. The vampire has been a remarkably fluid symbol for over a hundred years, standing for homosexuality, bohemianism and other hip manifestations of outsider status. Although the connection between the bloodsucking undead and romance fiction might seem obscure to the casual observer, they do share an ancestor. Blame it all on George Gordon, aka Lord Byron, the original dangerous, seductive bad boy with an artist's wounded soul and in his own time the object of as much feminine yearning as Edward Cullen has been in the early 21st. Not only did Byron inspire such prototypical romantic heroes as Heathcliff and Mr. Rochester (a character Meyer has listed as among her favorites), he was the original pattern for the vampire as handsome, predatory nobleman. His physician, John William Polidori, wrote "The Vampyre," a seminal short story that featured just such a figure, Lord Ruthven, patently based on the poet. Before that, the vampires of folklore had been depicted as hideous, bestial monsters.

Bram Stoker's Count Dracula was the English bourgeoisie's nightmare vision of Old World aristocracy: decadent, parasitic, yet possessed of a primitive charisma. Though we members of the respectable middle class know they intend to eat us alive, we can't help being dazzled by dukes and princes. Aristocrats imperiously exercise the desires we repress and are the objects of our own secret infatuation with hereditary hierarchies. Anne Rice, in the hugely popular Vampire Chronicles, made her vampire Lestat a bisexual rock star -- Byron has also been called the first of those -- cementing the connection between vampire noblemen and modern celebrities. In recent years, in the flourishing subgenre known as paranormal romance, vampires play the role of leading man more often than any other creature of the night, whether the mode is noir, as in Laurell K. Hamilton's Anita Blake series of detective novels or chick-lit-ish, as in MaryJanice Davidson's Queen Betsy series.

The YA angle on vampires, evident in the Twilight books and in many other popular series as well, is that they're high school's aristocracy, the coolest kids on campus, the clique that everyone wants to get into. Many women apparently never get over the allure of such groups; as one reader posted on Twilight Moms, "Twilight makes me feel like there may be a world where a perfect man does exist, where love can overcome anything, where men will fight for the women they love no matter what, where the underdog strange girl in high school with an amazing heart can snag the best guy in the school, and where we can live forever with the person we love," a mix of adolescent social aspirations with what are ostensibly adult longings.

The "underdog strange girl" who gets plucked from obscurity by "the best guy in school" is the 21st century's version of the humble governess who captures the heart of the lord of the manor. The chief point of this story is that the couple aren't equals, that his love rescues her from herself by elevating her to a class she could not otherwise join. Unlike Buffy, Bella is no hero. "There are so many girls out there who do not know kung fu, and if a guy jumps in the alley they're not going to turn around with a roundhouse kick," Meyer once told a journalist. "There's a lot of people who are just quieter and aren't having the Prada lifestyle and going to a special school in New York where everyone's rich and fabulous. There's normal people out there and I think that's one of the reasons Bella has become so popular."

Yet the Cullens, although they don't live in New York, are rich and fabulous. Twilight would be a lot more persuasive as an argument that an "amazing heart" counts for more than appearances if it didn't harp so incessantly on Edward's superficial splendors. If the series is supposed to be championing the worth of "normal" people, then why make Edward so exceptional? If his wealth, status, strength, beauty and accomplishments make him the "best" among all the boys at school, why shouldn't the same standard be applied to the girls, leaving Bella by the wayside? Sometimes Edward seems to subscribe to that standard, complaining about having to read the thoughts of one of Bella's classmates because "her mind isn't very original." But then, neither is Bella's. In a sense, Bella is absolutely right: She's not "good enough" for Edward -- at least, not according to the same measurements that make Edward "perfect." Yet by some miracle she -- unremarkable in every way -- is exempt from his customary contempt for the ordinary. Then again, by choosing her he proves that she's better than all the average people at school.

Such are the tortured internal contradictions of romance, as nonsensical as its masculine counterpart, pornography, and every bit as habit forming. Search a little deeper on the Internet and you can find women readers both objecting to the antifeminist aspects of Twilight and admitting that they found the books irresistible. "Sappy romance, amateurish writing, etc.," complained one. Still, "when I read it, I just couldn't put it down. It was like an unhealthy addiction for me ... I'm not sure how I could read through it, seeing how I dislike romances immensely. But I did, and when I couldn't get 'New Moon' I almost had a heart attack. That book was hypnotizing."

Some things, it seems, are even harder to kill than vampires. The traditional feminine fantasy of being delivered from obscurity by a dazzling, powerful man, of needing to do no more to prove or find yourself than win his devotion, of being guarded from all life's vicissitudes by his boundless strength and wealth -- all this turns out to be a difficult dream to leave behind. Vampires have long served to remind us of the parts of our own psyches that seduce us, sapping our will and autonomy, dragging us back into the past. And they walk among us to this day.

Shares