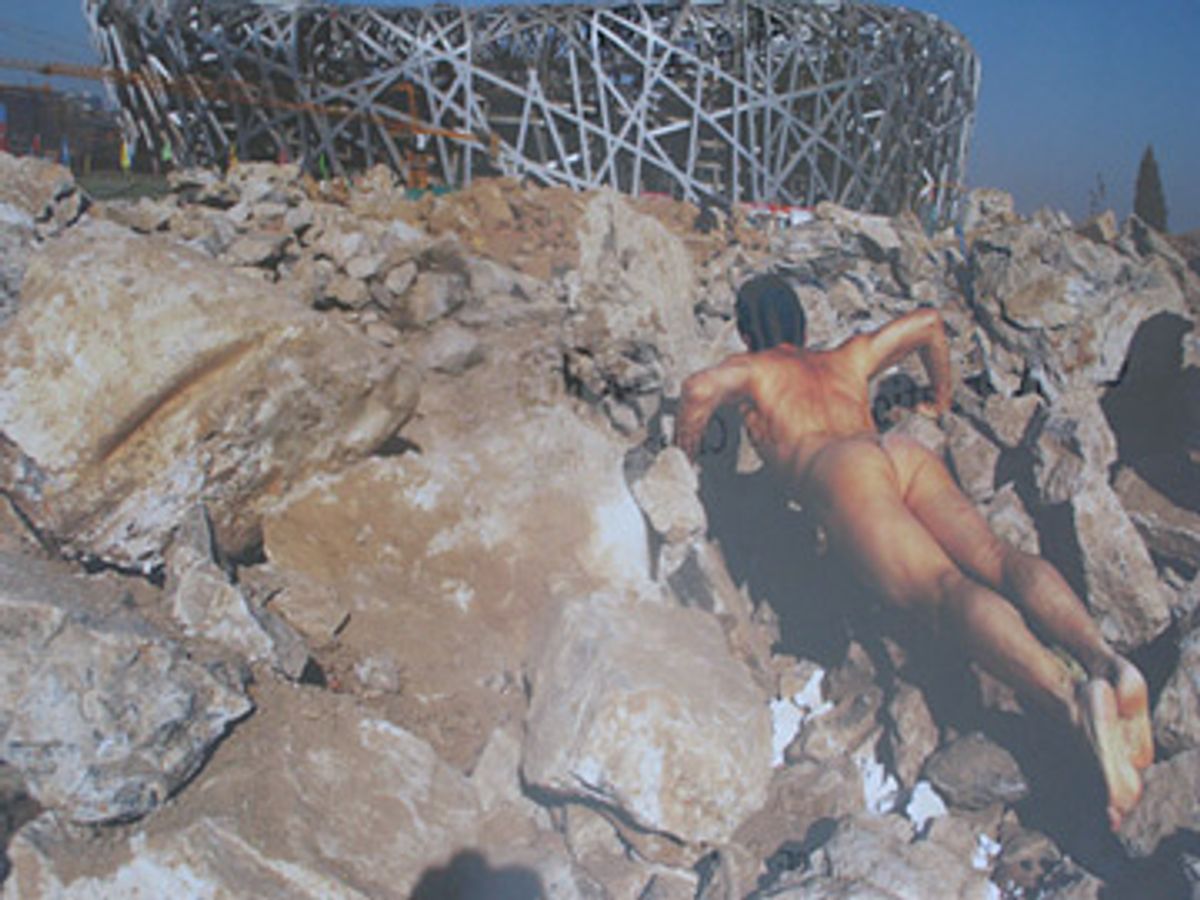

Photo by John Krich

Artwork from Beijing's 798 art district.

A contingent of merry, mindless militants from the bad old days wave a banner. But this one isn't red; it bears Olympic rings instead. A naked man sprawls illicitly in the tangle of construction rubble surrounding China's gleaming new stadiums. The vaunted symbol of the National Stadium is surrounded by waltzing security guards or columns of giant, Dali-esque ants, and a runner in one photo collage wears the entry number of the Tiananmen massacre: "1989."

Obliquely, but in more ways than anyone expected to be allowed, Beijing's estimated 10,000 artists are responding, if not participating, in the Olympics. But, as Huang Rui, a painter credited with founding the 798 art district, commented to me earlier, "The only golds, silvers and bronzes Chinese artists receive are for the rising prices."

On a spare afternoon between events, I headed for 798 -- which, in a country obsessed with lucky numbers, is fast becoming China's most well-known trifecta, designated by the government itself as one of the five top spots for Olympic tourists to visit. Named for a Czech-built electronics factory transformed into the compound's central gallery space, the area in a northeastern suburb called Dashanzi began like many an "artists" village in Beijing. I remember visiting the first of these scruffy encampments on the outskirts of town, where artists worked and began informally selling in cheap space far from the eyes of officialdom. Sometimes, it was not far enough, as I myself was once witness to a sudden public security raid in which several premature rebels -- one infamous artist signed his work with the name emblazoned across his white headband, "Evil Doer" -- were hauled off to indeterminate incarceration.

Back in the early '90s, I was introduced to a childhood friend of my ex-wife's. Even then, Ai Weiwei was a striking figure with his cultivated goatee, Mandarin tunic and dour manner. He had just returned to China after years of scrounging as a sidewalk artist and "King" of the East Village -- that archetypal artists village in New York. For all his underground credentials, he had taken residence in a wing of a very ample courtyard home -- the legacy of being part of a former cultural elite as the son of Ai Qing, the official poet of socialist ecstasy under Mao who was later sent to clean toilets in remote Xinjiang province.

Weiwei railed against the cultureless barbarity, fearful conformity and lack of international awareness in his homeland. He tinkered with making surreal objects (shovels covered in fur, etc.) à la Marcel Duchamp and helped organize shows, catalogs and galleries to counter officially approved realism, infamously under the slogan "Fuck Off." Later, I stayed in his big, minimalist studio compound in the open land around Beijing -- a first of many architectural experiments he took on -- where he also briefly sold antique furniture and amassed a collection of ancient objects that showed up in his sculptures and vase-shattering performances.

This time, he isn't answering my phone calls. And it isn't because he's in trouble for his many open calls to stay away from an Olympics staged by what he has labeled a tyrannical, fascist regime. On the contrary, he has an appointments secretary to filter requests because he has become so famous -- not so much for being the "godfather" of the Chinese avant-garde, with works now fetching millions in Europe, but because he is credited with inspiring the Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron with creating the main Olympic Stadium as a "bird's nest." On the eve of the Olympic Games, he published a statement in England on why he is continuing to boycott the icon he helped forge, though he has toned down his rhetoric a good deal, conceding the Olympics are a great moment for the country but hinting that the "courage" shown by the athletes and organizers should also be aimed at combating autocracy and restrictions on free expression wherever they are found.

If the arts have gone establishment, the other main symbol is 798. I was somewhat dreading to see the place full of ugly government signage, bland group homages to sport, encroaching fashion outlets, tacky souvenir stands and trendy cafes, even the presence of "museums" sponsored by Nike and others. Indeed, all of these are there, while many of the genuine low-rent geniuses have fled from gentrification and ever-increasing police patrols. Yet even the veteran nose-thumbing Gao brothers, while complaining they can't show their Chairman Mao outfitted with enormous breasts, had a new building and thriving rooftop cafe. Spurred by the slick, Belgian-funded Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, which aims to become the MOMA of China, many of the exhibits seemed better mounted and more wisely curated.

All in all, aside from direct reference to China's present-day leaders, or troubling issues like Tibet or workers' rights, everything from the authority shocking to the downright pornographic seemed to be on offer. Perhaps yesterday's striving artists are now driving BMWs, but, as a cultural asset, 798's wealth of sheer audacity and talent amid such sophisticated modernist design would be the envy of any other city in Asia, Tokyo included.

Not only that, but newer artists seem to be moving away from the knee-jerk use of campy communist imagery and the overdone merger of pop art with Chinese mythology, and heading toward more personal and less imitative ways of responding to the enormous material handed them by China's contradictions. China doesn't look to dominate just gold medal counts to come but world visual arts and photography as well.

How is it that Chinese young people seemed to "get" modern art, even performance and installation works, right from the start? And how to explain why Beijing has always been a center of ferment and enormous free personal space amid regimentation?

Maybe it's the yin of the yang, the opposite signs of the coin. But after my day at 798, I enjoy my first all-nighter, hopping from a party on a marble boat within an imperial park to a "bed" bar outfitted with antique platforms in the open air of a decrepit hutong courtyard to drunken strolling down the dark, silent and urine-soaked alleys of a tile-roofed China where all that counts, all that has ever counted, is how cleverly people can transcend their downtrodden state and declare their humanity to hidden no-name bars behind heavy doors where students shoot pool and shoot the shit until dawn.

As though to put a pointillist point on my day at 798, my taxi back to the hotel at 5 a.m. passes a young Chinese man standing in the midst of a major Beijing thoroughfare, completely buck naked but for the platform heels borrowed from his girlfriend.

So far, he gets my Olympic gold.

Shares