If Joe Biden's many years in the public eye have provided occasional material for his detractors, then far too little time has been spent listening to the substance and meaning of his remarks. Paying attention would have revealed that the unifying theme animating his views for three decades is the same concept that first motivated his entry into elective office: abuse of power.

Whether it's global or local -- from the Balkans and the Middle East to domestic violence -- Biden typically is among the first to respond when a cause pricks his conscience. For Biden, these are not merely political issues. They are personal challenges that compel action, usually in the service of a dutiful allegiance to the lessons hammered home by his parents. No speech, no interview, no television appearance is complete without reference to the guiding hands of Jean Biden and the late Joe Biden Sr.

Every reporter who has covered Joe Biden possesses dozens of stories referencing a familial anecdote or aphorism, all intended to provide a window into Biden's formative political thinking.

For example, nearly everyone on Capitol Hill has heard Biden quote his mother saying, "Out of every bad thing that happens, if you search hard enough, you'll find something positive." These weren't just words to get Biden through the personal hell of the loss of his first wife and daughter; they were the touchstones of his thinking in the immediate aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001. That is the basis of his oft-heard refrain during the Bush years that the worst thing this administration has done repeatedly for seven-plus years is squander opportunities.

Biden was keen to deliver justice to the Taliban and al-Qaida, but few others spoke with his eloquence about unifying a divided America, about taking advantage of Europe's sympathies, about how this was a moment to bring together the entire civilized world, emphasizing the important ties that could bind East and West to combat the new century's fascism, terrorism and intolerance.

In his father's worldview, there are the haves and have-nots, and what distinguishes them most is not acquisition of wealth or a particular lifestyle, but the humility and grace with which they handle their lot in life. Those who forget their roots, or whose station leads them to detachment from those less fortunate, are among the most irredeemable of souls in the Biden universe.

Biden loves to quote his father saying that "it's a lucky man who wakes up every morning, puts both feet on the ground, and knows what he wants to do." Biden reveres his father for many reasons, but surely one of the most important lessons is about duty and obligation, and to whom they are owed: to family above all else, but also to community and to oneself.

And it's also a call to action, to find a useful and productive life, humble and ordinary though it may be. Simply put: Stand up and be somebody. It would be more than enough for Biden if his tombstone read, "He made his family proud."

How does this play out in his approach to real-life political issues?

As the Balkan wars of the 1990s unfolded, few in Washington believed the United States should get involved in what appeared to be another round of a centuries-old, brutal conflict that seemed to promise only endless bloodshed for outsiders foolish enough to get trapped in someone else's ethnic struggles.

Biden has always been Eurocentric, defining America's interests as closely tied to the security of Europe, and convinced that the fate of southeastern Europe was inextricably linked to the well-being of the rest of the continent and, by extension, the United States. But the tipping point for Biden was the abuse-of-power issue he had absorbed from his father decades earlier, and he could not abide witnessing another genocide in Europe.

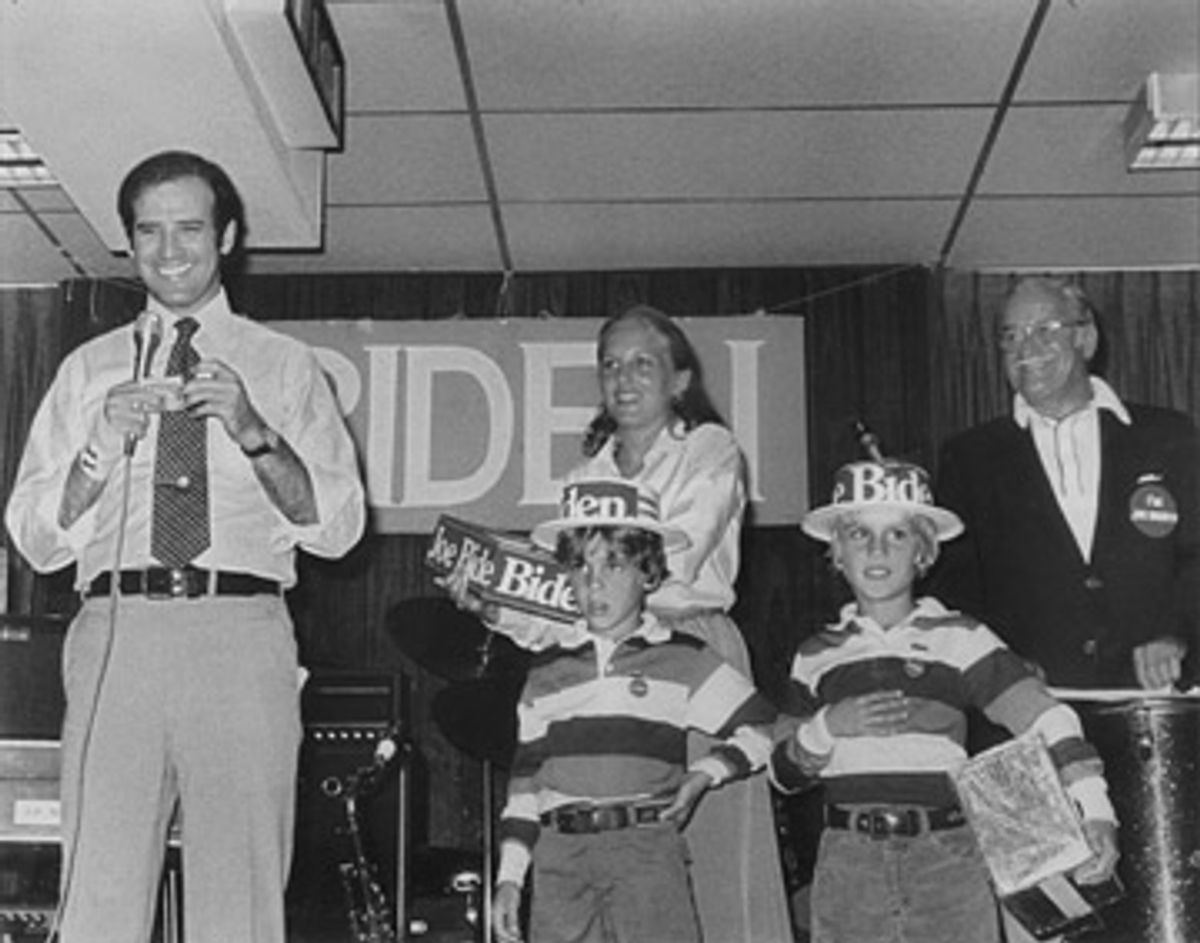

Many years earlier, when Biden's sons, Beau and Hunter, turned 13 little more than a year apart, he took them, separately, to the Dachau concentration camp outside Munich, Germany. It was critical for Joe Biden to teach his sons what his father had impressed upon him: the immorality and unacceptability of turning a blind eye to abuse of power, with Dachau representing the ultimate consequences of the unwillingness to confront evil.

Biden traveled to the Balkans virtually every year throughout the 1990s and finally succeeded in convincing an initially reluctant President Clinton -- and an even more recalcitrant Sen. John McCain -- that saving Muslim lives from a genocidal fate was a wise and just use of American military force. The iconic moment came in a face-to-face meeting between Biden and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic when the senator told the tyrant he was a "war criminal" who one day would be held accountable at the Hague, a prescient statement few others dared whisper.

Years later, accompanying Biden to Libya, I witnessed firsthand the senator's unique brand of personal diplomacy and his willingness to speak truth to power. Moammar Gadhafi had asked Biden to come to Libya to address a large convention at the time he was seeking a rapprochement with the United States. Biden agreed to go only after Gadhafi consented to a one-on-one meeting. We were ushered into Gadhafi's large tent in Sirte. There was minimal small talk before Biden asked why we were really there, why Gadhafi had embarked on his new approach. Gadhafi replied by asking, "Why not -- after all, the normal state of affairs between nations should be one of cooperation and friendship."

To which Biden responded without hesitation, "Well, you blew a passenger plane out of the sky, you've supported terrorists, and until recently you were developing nuclear weapons, that's why not." Gadhafi realized his jive had been rejected, and he resorted to honesty. "It's true we supported the PLO, the Sandinistas, the IRA and others, and they've all ended up on the White House lawn -- why not me?"

Biden succeeded in getting the despot to admit his real purpose was far from democracy building, as Gadhafi's single-minded interest was to secure Western know-how to develop Libya's natural resources quicker.

But the best moment came minutes later when Biden interrupted the maximum leader's soliloquy on the virtues of Libyan democracy by asking, "Please tell me, in your democracy can the people get rid of you?" After the translation was complete, it was hard to avoid glancing at the goons with automatic weapons lining the sides of the tent. "No, they can't," said Gadhafi, "because I am special. I started the revolution and they respect that."

"Oh, I understand," said Biden. "We had someone like that, too. George Washington. But after eight years, we got rid of him."

His commitment to passing his signature legislation, the Violence Against Women Act, similarly arose from lessons learned long ago about the moral centrality and need to uphold human rights and redress society's injustices.

Yes, Joe Biden can be glib. And he's the first to admit there are times he talks too much, even to his detriment, so that a phenomenal 15-minute speech turns into a good 25-minute speech and ends up as a maddening 40-minute speech.

But listen closely to what Biden actually says and means. Understand the values and principles that underpin his views. And try to appreciate his ability to connect the dots better than almost anyone else in public life when it comes to articulating a uniquely optimistic foreign policy and domestic agenda that are elevated by the simple but profound lessons learned in the humble home of Jean and Joe Biden Sr.

Shares