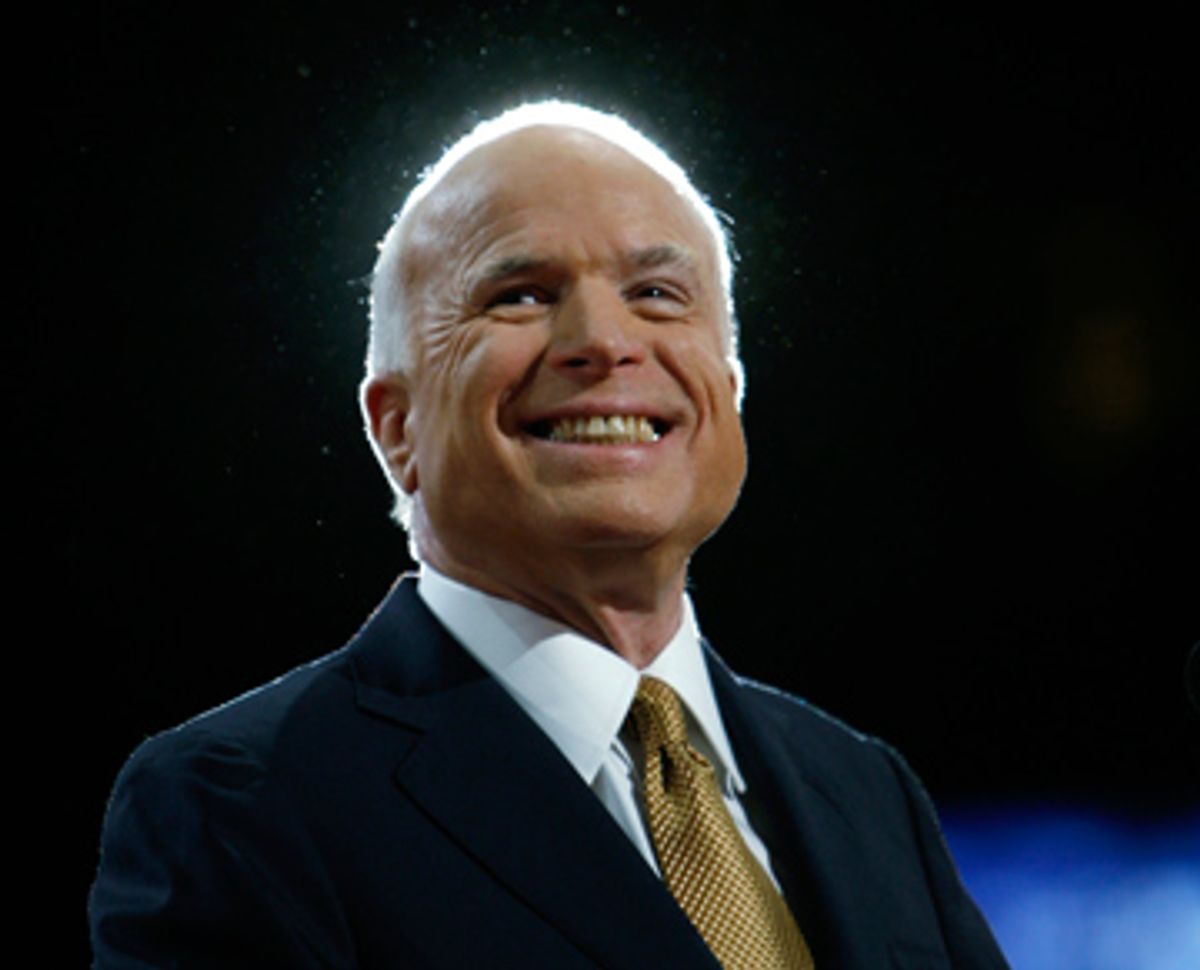

Eight years after he may well have transformed the Republican Party had he defeated George W. Bush for the nomination in 2000, John McCain finally had his moment to stand bathed in triumphant light at his party's convention. His acceptance speech Thursday night was a mirror of McCain the contradictory political figure -- sometimes unorthodox and daring, sometimes plodding and pedestrian; rich in character, light in policy substance, much stronger in its sincere tone than in its rhetorical gloss.

It was an imperfect speech, delivered by a candidate who modestly described himself as "an imperfect servant of my country," that does not begin to compare with Barack Obama's dazzling Denver finale or Sarah Palin's electrify-the-conservative-base star turn. But in political terms, McCain may have found the right words to appeal to the voters he needs to win, especially an older generation in hard-pressed normally Democratic industrial states like Michigan and Pennsylvania.

The overarching theme of McCain's speech -- wisdom through suffering -- could have been lifted from Greek tragedy. McCain retold his POW story with an honesty at odds with the hagiography that others at the convention have used to describe his heroism. ("They worked me over harder than they ever had before, for a long time, and they broke me.") But from that low point, "hurt and ashamed," he said that he was, in effect, reborn as a true patriot. "I was never the same again," McCain declared. "I wasn't my own man anymore. I was my country's."

No presidential nominee in American history has endured anything remotely akin to McCain's five and a half years as a prisoner in North Vietnam. That is why simplistic efforts to reduce McCain to a generic Republican -- a cardboard cutout from the Karl Rove book of paper-doll politicians -- fail to account for his periodic assertions of political independence. Even the glossy biographical film that preceded McCain's speech was filled with phrases rarely heard about a presidential nominee at his own convention: "Some call him hot-headed ... The isolation could have produced a bitter, broken man ... [He is] outspoken, brash, but honest."

That is why some of the strongest passages in the speech were an attempt to airbrush President Bush out of the history books and re-create a competent, conservative, non-corrupt Republican Party. "I fight to restore the pride and principles of our party," McCain said, while glossing over the identity of the individuals who so tarnished the Republican name. "We were elected to change Washington and we let Washington change us." In this cause of Republican reinvention, McCain even recycled a John Kennedy line from the 1960 campaign: "I will reach out my hand to anyone to help me get this country moving again." Both JFK and McCain took aim at a similar target: a hapless Republican president who had left the country stuck on a railroad siding.

American elections rarely grant a political party a do-over after an incumbent president fails most tests in office. The Republicans paid a price for Herbert Hoover for five presidential elections in a row. Hubert Humphrey was sacrificed on the altar of Lyndon Johnson's Vietnam War and Gerry Ford did not survive his efforts to disassociate himself from a president named Nixon. The reality that McCain, though trailing in most polls, is competitive with Obama is a tribute to the Arizona senator's resilience and his adroitness at playing the character card.

After two days of sliming Obama as an out-of-touch cosmopolitan who will endanger American security because he lacks Sarah Palin's experience, the Republicans shifted tactics in a belated effort to accentuate the positive. McCain even briefly hailed Obama and his supporters by saying, "You have my respect and admiration."

But that did not prevent McCain from later mocking Obama's charisma by claiming, "I'm not running for president because I think that I'm blessed with such personal greatness that history has anointed me to save our country in its hour of need." McCain also grotesquely distorted Obama's centerpiece domestic proposal by insisting that the Democratic nominee wants to "force families into a government-run healthcare system where a bureaucrat stands between you and your doctor."

At the Democratic convention, speaker after speaker assailed McCain's voting record, his presumed allegiance to Bush and his shopworn conservative domestic agenda. But with the exception of John Kerry, who lamented how McCain had changed in the pursuit of power, the Democrats dared not challenge their GOP rival's character. The Republicans, in contrast, have taken a Snidely Whiplash approach to Obama's character while finding it almost too tedious to joust with the Democrats on issues.

Both McCain and Obama owe their nominations in large measure to their diametrically different positions on the Iraq war. But while Obama has increasingly downplayed the Iraq issue to reach general-elections voters mired in the economic downturn, McCain is still running proudly as the Sire of the Surge. A year ago, who would have guessed that Iraq would figure more prominently at the Republican convention than when the antiwar Democrats descended on Denver? But like virtually everything in his campaign, McCain's talk of the surge is less about a formula for lasting victory in Iraq than it is a mechanism to again stress his sterling character in embracing an unpopular cause: "I'd rather lose an election than see my country lose a war."

As a naval aviator, who has both dropped bombs and been beaten as a POW, McCain spoke with quiet conviction when he said, "I hate war. It's terrible beyond imagination." Then abandoning, at least rhetorically, the jingoistic, go-it-alone style of the Bush administration, McCain stressed, "I will draw on all my experience with the world and its leaders ... to build the foundations for a stable and enduring peace." This section of the speech underscored McCain's political challenge in preaching strength to male voters (and moose hunters of the Sarah Palin variety) while reassuring women in particular that he will not heedlessly drag the nation into another war.

Little mentioned amid the fireworks in Denver and the balloon drops here in St. Paul is that for the first time since 1976, the American people will be permitted to hold a national election without a Bush or a Clinton on the ballot. In fact, it is difficult to imagine two more unlikely presidential nominees -- a survivor of a brutal prisoner of war camp and the first African-American to transcend American's segregationist past. Now that the conventions are over, it is worth fantasizing about a fall campaign that would prove worthy of Barack Obama and John McCain.

Shares