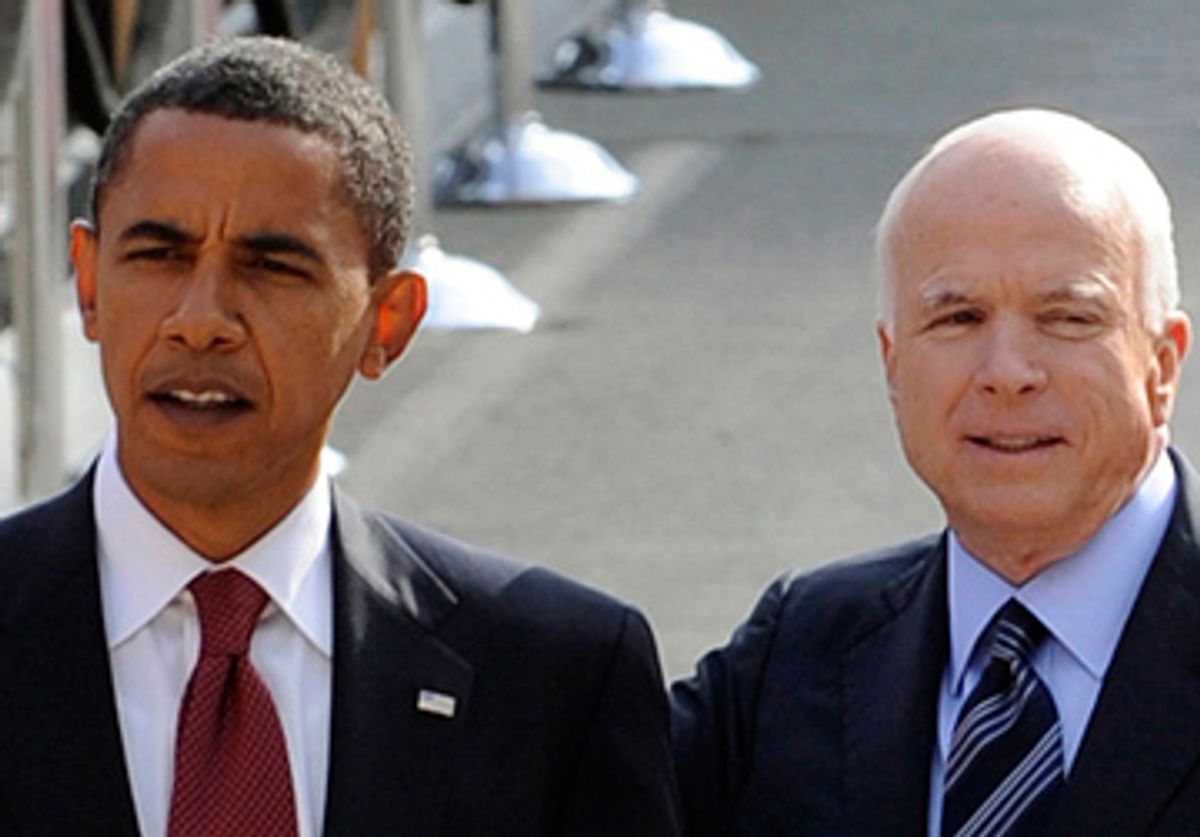

On the anniversary of 9/11, the virtuous John McCain showed up for a single day, as if the solemnity and sorrow of the occasion had penetrated his hard campaign carapace. From his joint appearance with Barack Obama at ground zero in the morning through their consecutive interviews on national service at Columbia University that evening, McCain reminded America that we have known a politician by that name who cared about honor, independence and decency.

Meanwhile, his newer doppelgänger appeared on television in horrifically dishonest and inflammatory commercials savaging Obama over sex education, assuring us smugly that "I'm John McCain and I approved this message." The vicious John McCain never went away, even for those few hours.

And that is the contradiction now confronted by the national press corps, whose members desperately wish to believe in the old McCain they adored rather than the new McCain who nauseates them. Some pretend that what they see is not really happening, or doesn't matter; others wrinkle their noses but cannot quite muster indignation; and a few, very few, realize that the campaign is being debased by the man who once denounced this ugly style of politics and promised reform.

Probing those issues is sensitive and painful for the press corps that still loves him, but the Arizona senator's appearance at Columbia to discuss national service -- a safe, worthy topic that does not lend itself to Swift-boat-style attacks -- provided a perfect opportunity for two nationally prominent journalists. Judy Woodruff of PBS and Richard Stengel of Time magazine, the Columbia forum's interlocutors, were plainly relieved to encounter the agreeable McCain who says only kind things about his opponents, prays for the recovery of his beloved friend Ted Kennedy, understands the importance of government, and speaks movingly about the values that unite us as Americans.

That smirking creep who accuses Obama of wanting to subject 6-year-olds to "comprehensive sex education" was not onstage. Instead there was only a familiar fellow whose answers, while occasionally dotty or inelegant, were nevertheless always well meant and sometimes witty.

Many of the questions posed by Stengel and Woodruff were softer than cotton candy. ("Senator, we have less than a minute in this block. But do you think the length of your service in Washington gives you a unique understanding of the changes that need to be made?" asked the gentle Judy.) Such indulgence may have been inevitable under the circumstances, since the service forum was not a press conference or a debate. Tough interrogation might have looked like an ambush.

For everyone involved, in any case, the clear agenda was to establish the next administration's legislative and programmatic benchmark on national service -- and that was accomplished when both Obama and McCain committed to expand AmeriCorps and encourage other volunteer initiatives, both public and private. That left plenty of time for meandering discussion of the importance of national service, the exceptional character of America and other matters that called for patriotic bloviation. To their credit, Woodruff and Stengel did not wholly avoid the sore subject of that other McCain. But they didn't press hard.

When Woodruff asked him about the "derisive" attitude toward Obama's community organizing expressed by Sarah Palin and other speakers at the Republican convention, she gave him the opportunity to disown that "kind of language."

McCain's response was revealing -- not because he said anything new but because he adopted the same style of obfuscation that the politicians of the Bush family have traditionally used to distance themselves from the thugs who act on their behalf.

He began by acknowledging that politics "is a tough business." Then he tried to blame Obama by suggesting that "the tone of this whole campaign would have been very different" if only the Democrat had accepted his proposal to hold a dozen joint town hall meetings. He said that Palin was only "defending herself" by attacking Obama. And finally he claimed, contrary to every utterance on the subject at his convention, that he respects Obama's "outstanding" record of community service.

This exercise in excuse making went unchallenged until Stengel asked McCain whether the "ugly" tone of politics would drive young people away from public service -- and what had happened to his hopes and promises of a "different" and "high-minded" campaign.

"Has it been rough? Of course. And again, it isn't the final recipe or the only answer," he replied, again demanding that Obama accept his "request" to "go around America" together. This sounded more and more like a rehearsed response. Woodruff followed up by asking plaintively whether it "is naive of people to expect that politics could be a little less rough-and-tumble and even nasty."

McCain's answer was the same as that a man like Karl Rove might offer:

"The people make the final judgment with their votes. They make the final judgment about campaigns and how we present ourselves to the American people. And I think that that will be the ultimate test of what kind of campaigns do we run."

In other words, the only test of campaign tactics is whether they work. So now we know that there are not really two McCains, one good and one bad. There is only one McCain, and he has two faces.

Shares