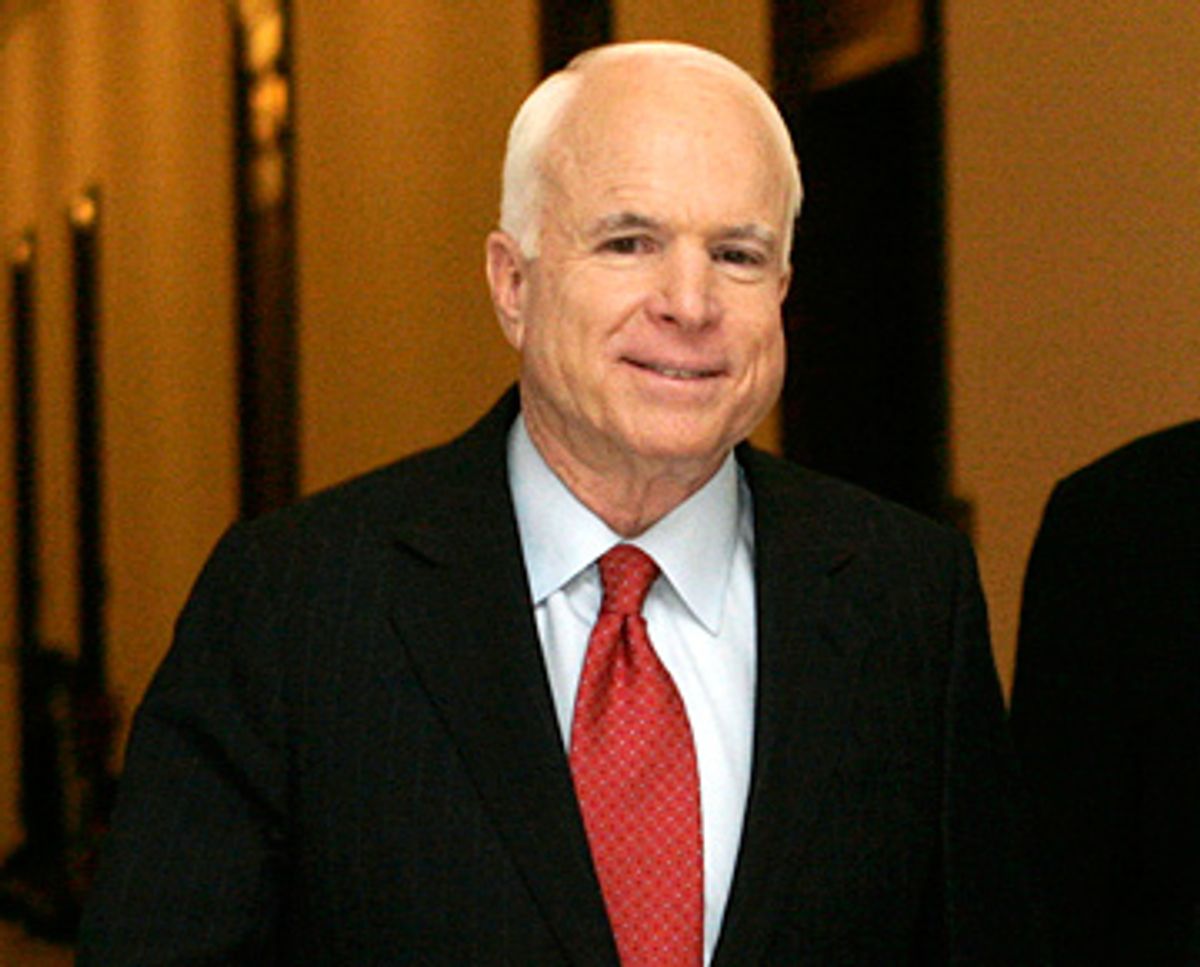

John McCain's incoherent and opportunistic campaign, which he never "suspended" for 30 seconds, now poses an imminent threat to the world economy. Nobody in the McCain camp, including the policy-challenged candidate, seems able to articulate a firm position on how to restore the stability of the financial markets and prevent a catastrophic lending freeze.

Instead, the Arizona senator is running around trying to insert himself into photo ops and ingratiate himself with House Republicans whose only apparent objective is ideological obstruction. How can he provide leadership when his own viewpoint is increasingly opaque -- and the only thing that remains clear is his desperation about his worsening poll position?

Actually, McCain was clearer in his positions and objectives before he went to Washington for the White House meeting that blew up negotiations over a bailout bill on Thursday afternoon. When he showed up at the Clinton Global Initiative for a breakfast speech, he reiterated his promise to stop campaigning and return to the capital, where he hoped that Barack Obama would join him in "putting politics aside" and "dealing in a straightforward bipartisan way" with the bailout legislation. "I'm an old Navy pilot," he said, never missing a chance to mention his war record, "and I know when a crisis calls for all hands on deck."

The Republican nominee then went on to enumerate five critical issues that had to be resolved before the Treasury proposal could have any chance of passage: a bipartisan oversight board; a provision for taxpayers to recover at least a portion of the Treasury funds; a completely transparent process for expenditure of those funds; a rejection of any "earmarks" for favored companies or any other purpose in the bill; and a guarantee that no Wall Street executives will profit from taxpayers' money.

On those issues, as of approximately 9:30 that morning, McCain declared he would be unyielding and yet bipartisan. "In this crisis, we must work together again ... We must draw on the best ideas of both parties and work together for the common good."

Those particular clichés were irrelevant to the problem at hand on Capitol Hill, as he should have known by then but surely learned when he arrived in Washington -- where the ideas of Republicans and Democrats in the House are diametrically opposed. His Republican colleagues in the Senate were on the verge of agreement with the Democratic congressional leadership in both houses and the White House until the House Republicans decided to smash the bipartisan plan.

Amazingly, McCain decided to connive with the right-wing bloc -- in contradiction of his own stated objectives and his supposed bipartisanship, which Democrats in both chambers plainly shared. At the White House meeting he reportedly said almost nothing, except to indicate that he was working with the House Republicans (which their spokesman, Rep. Mike Pence of Indiana, confirmed later). He sat passively while House Republican leader John Boehner sabotaged the agreement with a phony mortgage insurance proposal.

Yet the tentative agreement that the Republican minority capsized, with his assent, met all of the requirements that McCain had listed as necessary for his support only hours earlier! The original deal announced by the congressional negotiators, with the assent of the White House and the Treasury, stipulated that the bailout would be subject to strict oversight by an independent inspector general and regular Government Accountability Office audits. Any "inappropriate or excessive" compensation would be forbidden to executives whose firms received bailout funds, and the government would take equity shares in those companies to protect the interests of taxpayers.

Well before the end of the day, however, McCain had abandoned the positions he had taken at the Clinton breakfast -- and his spokesman was insisting that the senator had no firm position on the bailout bill because he wanted to be in a position to lead. Or something like that.

There was never any likelihood that McCain would make any independent intellectual contribution to the discussion at the White House, or anywhere else. But he could have helped herd House Republicans into an agreement that met the criteria he had claimed were important to him, in the bipartisan manner that he had demanded in such ringing words. He didn't, because he meant none of it.

By the time you read this -- and certainly by the time he appears in Oxford, Miss., for the first presidential debate -- the former straight talker will probably have adopted some new stance, in his panting eagerness to appear presidential. His attempts to game this dangerous situation, his waffling between bipartisanship and ideological rigidity, his shiftiness on the real issues and his obvious lack of concentration on the problems that must be resolved -- suggest that he is in fact unfit to serve in the office he desires. Once again he has proved that his claim to put country first is hollow. He was more than willing to take America down as he gambled for that prize.

Shares