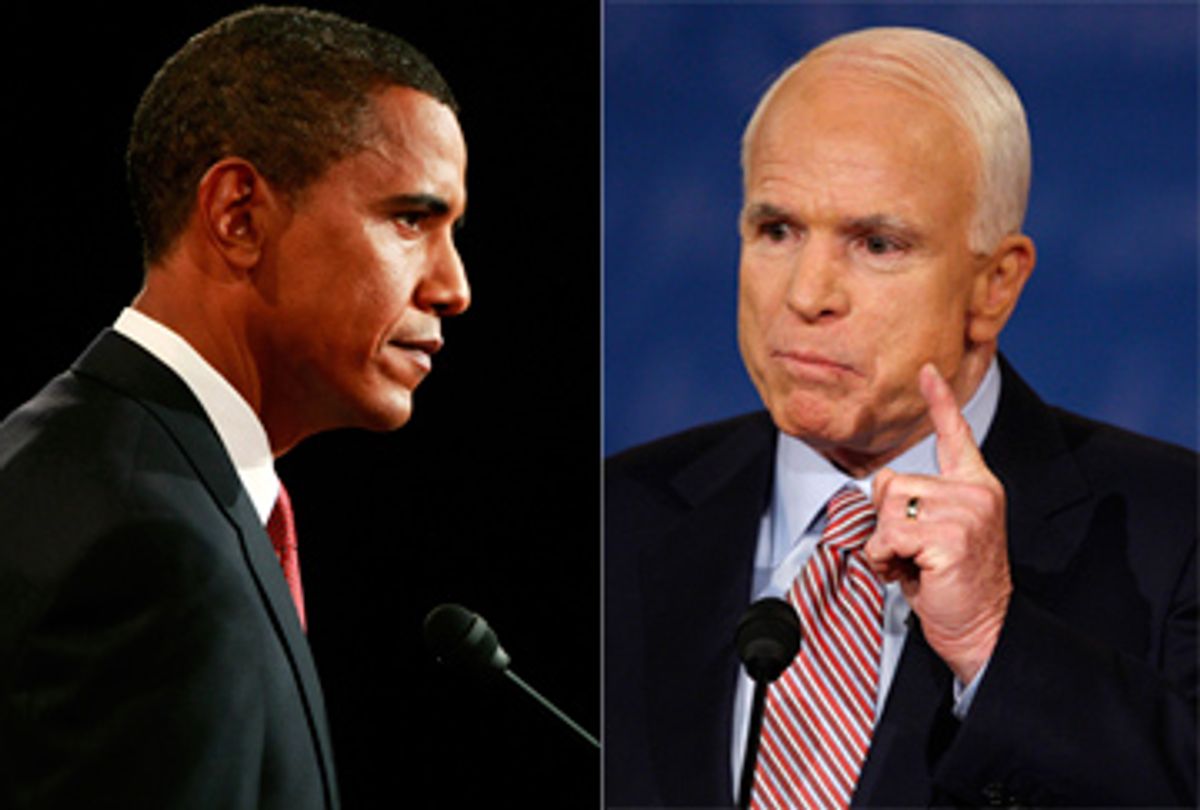

Forty-eight years ago when John Kennedy and Richard Nixon faced off for an hour in a television studio in Chicago, the idea of two presidential nominees meeting on the same stage for a clash of ideas was electrifying. Friday night in Oxford, Miss., when Barack Obama and John McCain stood at dueling lecterns for the first time, both candidates sometimes found it difficult to ignite.

The debate went 97 minutes by the clock, but at times it played longer. For most of the evening, both cautious and well-programmed candidates conducted the debate as if it were the opening salvo of a long war, not a conflict that would be decided by a lightning thrust of a sudden breakthrough. It was almost as if the whole thing was a rehearsal for the two more presidential match-ups to follow, not to mention next Thursday night's land-of-contrasts debate between Sarah Palin and Joe Biden. It is tempting to split the difference and call the imperiled-until-the-last-moment Miracle in Mississippi debate a draw. But what is almost impossible to assess (and, please, do not regard the overnight polls, the focus groups and the instant analysis from the pundit pack as definitive) is how this eagerly anticipated telecast played with undecided or persuadable voters.

For a candidate who claimed that he had spent the prior 48 hours concerned only with the future of the American financial system (and almost did not make the odyssey to Oxford), McCain certainly had a steel-trap memory for attack lines. Especially when the topic turned to foreign policy in the second half of the evening, McCain was like a bantam-weight fighter trying to win a bout on points by peppering Obama with tiny jabs (some of them wildly misleading). Obama -- who could frequently be observed shaking his head and quietly saying, "That is not true" -- tried to be both resolute and reassuring without losing his composure. The back-and-forth details of the debate may have mattered less than the first-term Illinois senator's ability to say with conviction, "That will change when I'm president of the United States."

Obama's weakest moments may have come when he tried too often to be a consensus builder even there onstage wrestling for possession of the Oval Office. "Sen. McCain is absolutely right" seemed to have been Obama's mantra for the evening. McCain, even though he began the evening with a hymn to bipartisanship, did not return the favor. Playing Nixon to Obama's Kennedy, McCain repeatedly tried to portray his rival as untested and unready. As the two men sparred over Obama's belief that rigorous pre-conditions should not deter America from negotiating with nations like Iran and North Korea (an issue that had been a point of contention with Hillary Clinton in the primaries), McCain snapped, "This is dangerous. It isn't just naive; it's dangerous." Stressing Obama's purported inexperience, however, may be a risky tactic for Republicans less than a week before Palin (who governs a state smack-dab between Russia and Canada, thank you) debates Biden, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Both Obama and McCain were much crisper when moderator Jim Lehrer toured the world's trouble spots (Iran, Afghanistan, Georgia) in what was originally supposed to be a national-security-only faceoff than during the first half of the debate when the topic switched to the American financial crisis. The difference between the two halves of the debate was an illustration of the virtues of rehearsal (they both had mastered their foreign-policy briefing books) versus the fuzziness of spontaneity (neither candidate ever mentioned Washington Mutual, whose collapse this week was the biggest bank failure in American history).

The 72-year-old McCain did little to gloss over his age, boasting at one point that Henry Kissinger has "been my friend for 35 years," which would date the relationship back to 1973, the year of Obama's 12th birthday. But while McCain never became lost in his prepared remarks (as the then-73-year-old Ronald Reagan did during his first 1984 debate with Walter Mondale), there were a few times when the Republican nominee might have said, "Stop me if you've heard this one before." McCain, for example, twice said that he had not been elected "Miss Congeniality in the United States Senate." More tellingly, though most voters presumably missed it, old national-security-hand McCain stumbled over the pronunciation of a series of names of world leaders, struggling to master Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (Iran) and Asif Ali Zardari (Pakistan).

During the free-form final moments of the debate -- when a question about a possible terrorist attack morphed into the equivalent of closing statements -- Obama resorted to a bold tactic as he went out of his way to stress his unusual parentage: "My father came from Kenya. That's where I get my name. And in the '60s, he wrote letter after letter to come to college here in the United States because the notion was that there was no other country on Earth where you could make it if you tried. The ideals and the values of the United States inspired the entire world. I don't think any of us can say that our standing in the world now -- the way children around the world look at the United States –- is the same." This gambit, which almost certainly had been honed during debate prep sessions, clearly reflected a political calculation that up-for-grabs voters yearn for, well, morning in America to replace the bitter aftertaste of the Bush years.

The immediate aftermath of a presidential debate is a prime time to acknowledge the built-in limitations of the omnipresent political polls. Even if Wall Street were healthy (ha!), too much would be happening in too short a period of time right now for public attitudes to harden into something that is reliably measurable. In a conference call with reporters Tuesday, McCain's pollster Bill McInturff accurately described the period from the first debate until the final one (Oct. 15 at Hofstra University) as "a two-and-a-half-week black hole." As McInturff put it, "We'll wait three or four days after those last debates are over -- and we'll know where we'll be at." McInturff's comments -- which were made before McCain put the debate into jeopardy -- came across less as spin than as an admission of humility by a veteran Republican pollster.

Passionate partisans may be the worst debate judges in the world, since they find it nearly impossible to grasp how voters still unsure of their presidential pick would react to seeing Obama and McCain go head-to-head. For all the needling fact-check press releases from both campaigns, nothing said by either candidate Friday night seemed like an obvious gaffe that would be remembered by undecided voters on Election Day. In all likelihood, more Americans were confused than convinced when the debate devolved into penny-ante disputes that Obama dismissed as "Senate inside baseball."

Friday night was not a transformational moment like the first Kennedy-Nixon debate. Some swing voters may have found McCain mean or Obama green. But most voters -- and this is an impressionistic guess -- may have regarded the Oxford debate merely as the slow-starting first act of a potentially gripping three-act drama, one likely to end with fireworks and fisticuffs at Hofstra University on Oct. 15.

Shares