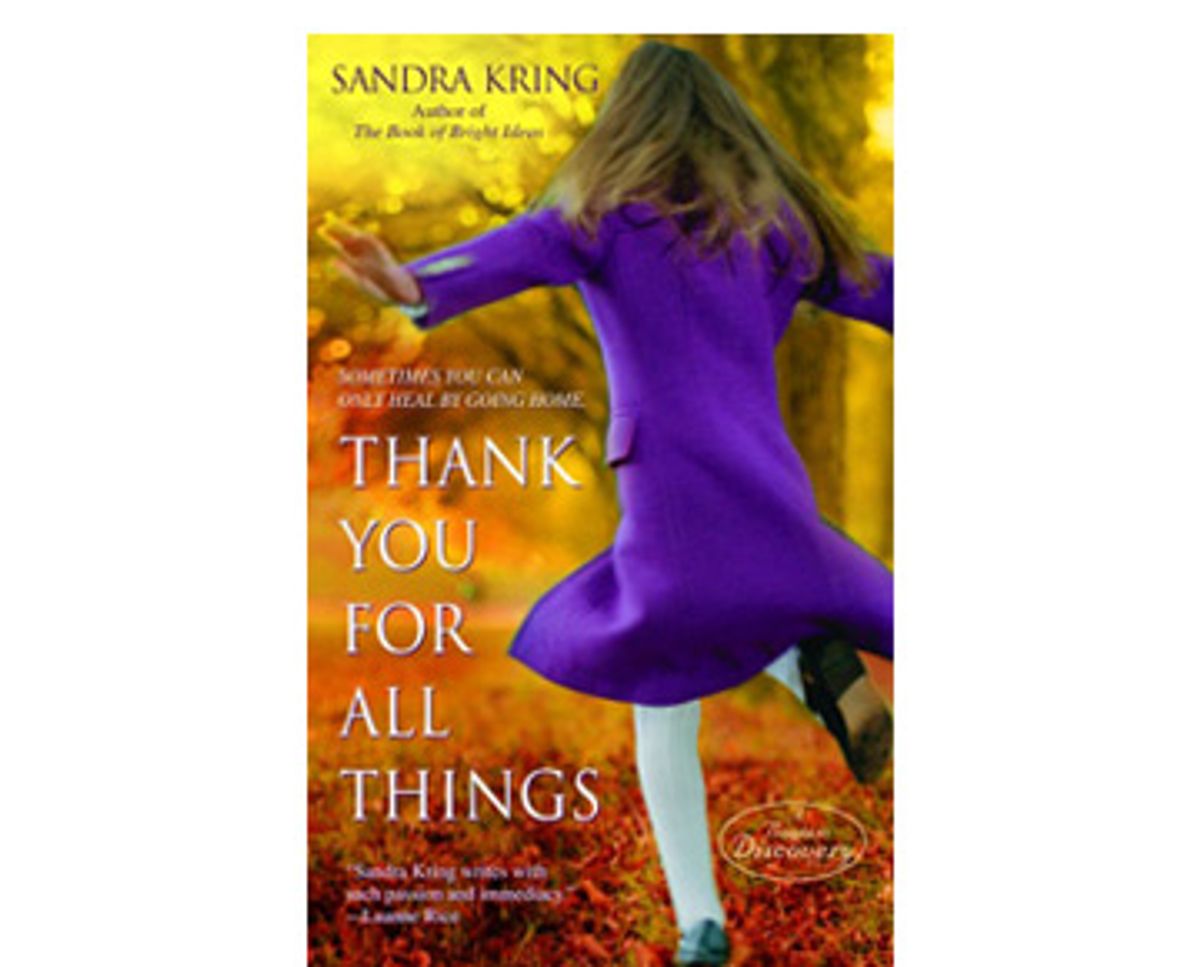

Sandra Kring's delightful and nuanced take on Midwestern America in "Thank You for All Things" feels real and moving -- perhaps because it is so unpretentious.

Like the author's previous books, "Carry Me Home," about a brain-damaged teen who goes off to WWII, and "The Book of Bright Ideas," a tale of two eccentric young girls in the early 1960s, "Thank You for All Things" is set in Kring's home base. The time frame of the new book is contemporary, but some of the themes at work in her previous novels -- the difficulties of adolescence in small-town America, dysfunctional family problems -- have returned and taken even more prominence here. "Thank You" is populated by a deeply messed-up, quirky family comprising three generations. As a group, they are exceptionally intelligent but frustrated and poor, unable to overcome the legacy of violence that has been handed down from Grandpa Sam, who once put his wife Lillian's head through a wall, among other abuses.

The story unfolds from the point of view of Sam's precocious granddaughter Lucy, an unusually empathetic and insightful 11-year-old, though average compared to her twin brother, Milo, a physics prodigy. (Milo's latest project is memorizing the digits of pi.) Lillian, their grandmother, has convinced the twins' mother, Tess, to return to the northern Wisconsin home where she grew up because Sam is dying from mini-strokes and congestive heart failure. Grandma considerably sweetens the sour pot by suggesting that her daughter Tess, a destitute skeptic who writes Christian romance novels for the money, might inherit the house.

A single mom, Tess has kept her twins in the dark about the identity of their father for a long time. Lucy, who fantasizes that he is, among other things, skater Scott Hamilton or a donor to the Nobel sperm bank, hopes to find out something about him from her other relatives and people in the small town. But Tess returns to her hometown only grudgingly; this is the place where a deeply unsettling story about her children's father is set. To reveal it here would be to spoil the book's climax, so let's just say that it's an event dramatic enough that it caused Tess to give up on men entirely. She even rebuffs the earnest advances of her most recent boyfriend, Peter, an infallible, sensitive dude her children clamor for like the dad they never knew. Tess confesses her tormented love for Peter in her journal, which Lucy copies off her mother's computer and reads feverishly, desperate to understand her mother and learn about her family's history.

With a story like this, the risk of sentimentality runs high, and Kring doesn't completely escape moments of unearned pathos. However, she draws her characters very carefully, with wonderfully odd but never extraneous details: Grandpa Sam hates red squirrels, Lillian arranges tables according to principles of feng shui. When Lucy gets emotional, she tends to lose some of her critical distance from, say, her grandmother's immersion in flaky New Age ideas. Based on Lillian's discovery of the Ojibwa belief that if you offer tobacco to an eagle, he will carry your prayers to heaven, Lilian stops the car on the way to Grandpa Sam's house and gives Lucy a cigarette, the contents of which the girl tosses into the air. Lillian regularly consults an "intuitive" named Sky Dreamer, and keeps trying on new names, including "Persephone." Unfortunately, Kring uses some of Lillian's kookiness to support the novel's main points about life -- the tobacco offering returns at the close of the book. But during low-stakes moments, like descriptions of Wisconsin's autumn landscape, Kring's style takes wing:

It is quiet here. Peaceful. I smile as the breeze brushes my cheeks and dries my eyes as if I'm ice skating. I look to the north of the house, where the red maples in low-lying spots are blotched with deep red, and to a patch of sugar maples that are just beginning to tinge with a brighter, orangier red, and I wonder how tall those trees were when Mom was a kid ...

The simplicity of pastoral scenes like this one, and throughout "Thank You for All Things," contrasts elegantly with the turmoil inside the house. At one point, nearly the whole town descends on the place: Lillian, Tess, her estranged brother and sister, a Native American neighbor, Grandpa Sam's mistress, and local madam Maude Tuttle all become tangled in an angry, complicated knot of shared-but-disagreed-upon history.

Kring compares the anger that lets loose in the aftermath of Grandpa Sam's death to a series of rubber bands snapping, and that understatement only barely describes the explosion of grief and accusation that marks the novel's deliciously soap opera-like climax. Lucy only begins to unravel the knot in the final chapter, when she gives a touching, perceptive and honest eulogy for her grandfather -- the sort of eloquent tribute that could only be more moving in real life. By that time, happily, the McGowan family feels utterly genuine.

Shares