The funniest comic strip currently running doesn't appear in any newspapers. Until very recently, Chris Onstad's 7-year-old "Achewood" -- a warped fantasia about a bunch of anthropomorphic animals getting into trouble -- was almost entirely an online phenomenon. Onstad has self-published nine collections of the strip, but "The Great Outdoor Fight," a hardcover edition of a story line from 2006, is the first "Achewood" book to be widely distributed, and it suggests that the native format of the American daily strip is shifting, very quickly, from newspapers to the Internet.

Online comic strips are barely out of their infancy. There has been a lot of theoretical discussion of the ways cartooning on the Internet might take advantage of not being printed on paper, from motion enhancement to the "infinite canvas" of the computer screen, but relatively few Web comics are both technologically innovative and worth seeking out. Most of the best online cartoonists' work, in fact, still looks a lot like newspaper strips, in much the same way that early TV shows tended to be very much like successful radio shows but with pictures. "Achewood" is no exception. In some ways, it's formally conservative; Onstad's minimalist artwork has a lot in common with strips from "Garfield" to "Life in Hell" to "Dilbert," all of which are designed to get their visuals across even when they're squished down to the postage-stamp dimensions at which most papers run their funnies.

But it's impossible to imagine "Achewood" running next to "Blondie" and "The Family Circus," for reasons that have to do with both its form and its content. Onstad is in a position where he can do anything he wants with it. If a strip's not ready to go on a particular day, he skips a day; individual strips can be as short or long as they need to be. His characters can curse up a storm. He can mess with the tone of "Achewood" any time he feels like it (and the strip's rare failures are mostly ambitious experiments rather than going-through-the-motions gags). He isn't beholden to a syndicate, or to daily newspapers' need to worry about offending their audience, or to anyone except himself. "Achewood" couldn't possibly have evolved without the Web -- not because of its "infinite canvas" but because of its infinite possibilities.

The flip side to comic strips' liberation from print is that the most successful Web comics -- "PvP," "Diesel Sweeties," "Wondermark" -- often turn into print books eventually, and some work better than others when they're transferred to wood pulp. "Achewood" makes the transition to print miraculously well. "The Great Outdoor Fight," in particular, works as a stand-alone story; Onstad doesn't bother to explain who any of his characters are, but their personalities and relationships are obvious from the get-go.

The core of this volume is the friendship between Ray Smuckles, a wealthy, reckless cat, and his best friend, a brilliant but withdrawn cat who goes by the nickname Roast Beef. Art about male friendship is a tricky thing to pull off, and very often contextualizes it in violence -- a tradition that Onstad pushes to its parodic limits. "The Great Outdoor Fight," as its title suggests, is also all about dudes wailing on each other: The GOF is a long-standing annual event ("3 days. 3 acres. 3,000 men"), in which guys pummel each other until only one is left standing, and that final combatant becomes a cultural hero.

As usual with Onstad's stories -- and even, sometimes, his individual strips -- "The Great Outdoor Fight" starts nowhere near where it ends. Todd, a stuttering cokehead squirrel, hits up Ray for venture capital to create a series of anatomically incorrect attachments for cellphones, which somehow leads to a visit from Ray's mom, who drinks a little too much Chablis and lets it slip that the father Ray barely knew won the Great Outdoor Fight in 1973. Ramses Luther Smuckles, as it turns out, was a pioneering fighter -- as Roast Beef puts it, "He was like the Thomas Edison of handing a dude his ass!" -- who fought under the name Rodney Leonard Stubbs ("The Man With the Blood on His Hands"). And although he never quite says so, Ray is clearly desperate for some kind of connection with his father.

So Ray qualifies himself for the fight by devious methods, signs himself up as "Son of Rodney" and joins forces with Roast Beef, who knows much more about the GOF's history and traditions. Between Beef's strategic insights and Ray's inherited gift for mayhem, they manage to demolish most of the competition, although Ray has second thoughts once he has blood on his own hands. But only one man can win the Great Outdoor Fight, and Ray realizes he may have to thoroughly kick his best friend's ass -- the rules, in fact, say he has to "beat him 'til he can't crawl, see, or cry" -- since the last two men standing have only an hour to settle their conflict until the organizers run them over with Jeeps.

Summarized like that, "The Great Outdoor Fight" doesn't sound nearly as funny as it is. But that's part of why it works as well as it does: Onstad wisely builds a rock-solid dramatic structure beneath the story's flurry of absurdity. That's an impressive trick, since he's also clearly winging it -- he has claimed that he never plans his story arcs ahead of time, and has also noted that he "had no idea what the Great Outdoor Fight was before like the eighth panel of nine in the strip right before it became something."

Onstad's flavor of comedy takes a while to get used to (although it also gets funnier with repeated readings). He virtually never bothers with conventional punch lines, and he plays almost all his jokes absolutely straight. One of the "bonus features" included in the new book is a deadpan glossary of Great Outdoor Fight terms: "A fighter who is 'Made in the Milling' comes by his victories naturally, without strength or combat training, study, nutritional supplements, the development of personal philosophies, or use of alcohol or drugs (unless he has used drugs and alcohol since very early in life)." There are at least six jokes built into that sentence, and all but the last sneak up on you.

As with "Arrested Development," one of the few comedies that works at all like "Achewood," Onstad's humor is often cumulative: Ray's habit of using "the hell" as an all-purpose intensifier ("The hell look at all that mayhem") is amusing on its own, funnier as he keeps doing it, and funnier still when it becomes clear from context where he picked it up. And when Roast Beef, who always speaks in a smaller-than-normal font with no punctuation, actually uses an exclamation point or two, it's obviously a big deal; it's also hilarious once you notice it.

Onstad's not particularly virtuosic as an artist: He sticks to a single line thickness, never draws a background if he can possibly get away with it, hides virtually all of his characters' eyes behind glasses, and recycles the same few three-quarter head-and-upper-torso shots whenever feasible. He lets his language handle what his drawings can't. (We don't actually get to see Ray taking on many of the GOF's "tick-pimps, boilbacks, and yard-sleepers" -- although Onstad's invention of all three of those slurs to toss off in a single caption is funny enough that it doesn't matter.)

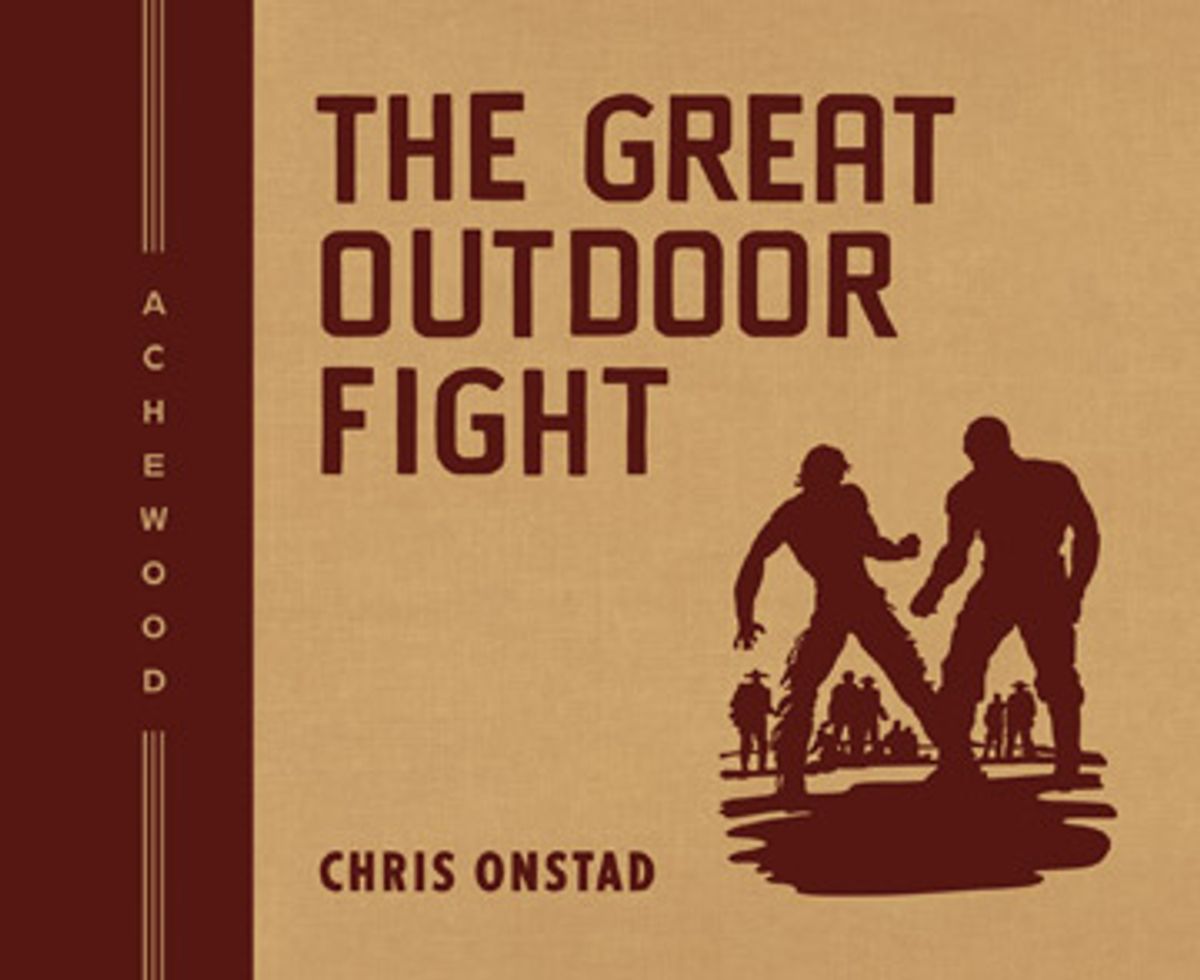

Still, Onstad can make a few lines say a lot -- Ray's emotions are almost entirely conveyed by the tilt of his eyebrows and the position of his paws -- and his visual strengths are storytelling and, especially, design. A single image of Roast Beef and Ray's conscripts for their army (a hapless, ectomorphic cat with a leather aviator helmet and a little Black Flag logo tattoo; a leather-jacketed, mustachioed thug who calls himself "The Latino Health Crisis") gets across everything we need to know about them. The cover of "The Great Outdoor Fight" is a hilariously dead-on evocation of a vintage boys adventure hardcover, right down to its embossed type, and the endpapers feature immaculately pastiched GOF posters from 1924, 1943, 1957 and 1969. You don't even have to look at the text to tell what year they're from.

His dialogue is enormously quotable, like "The Big Lebowski"-level quotable. ("I ain't Frederick H. Coca-Cola but I do know something about building a brand.") But it all works to build the slower, deeper comedy that comes from "Achewood's" characters -- Onstad inhabits his characters so fully that he used to write blogs as a bunch of them. Roast Beef, in fact, also writes a print zine, "Man Why You Even Got to Do a Thing."

"The Great Outdoor Fight" even works as an example of the thing it's parodying. The GOF is a childhood fantasy of awesomeness, a battle royal to end all battles royal, the ultimate There Can Be Only One -- and it's also sort of awesome. It conflates masculine glory and macho clichés and pro-wrestling burlesques of macho clichés until it's impossible to tell which is which. Its traditions are both sacred and ludicrous, just like real traditions: The army captains who emerge by the second night are presented with a feast of turkey, brandy and NoDoz, which they can either eat themselves or give to their men, but not both. There's a terrifically twisted version of the inevitable scene in which our heroes are sizing up their opponents' weaknesses: "It turns out Ron's wife has extreme problems with credit-card debt," Beef notes. "It causes him great stress and his trapezius muscles are knotted all to hell." (Beef gets one of Ray's minions to summon the unlucky, tense fighter: "Tell him Son of Rodney is about to sell his wife a 29-Minute Ab Minder.")

As preposterous and aware of its own tropes as it is, the GOF ends up stumbling onto actual emotional depth and momentum anyway -- there's real suspense over how it's going to turn out. (Even Beef and Ray's friends back home get so excited about the fight that they come to blows themselves, just to get in on the joy of ass-kicking.) By the time the book's plot takes its last few grand, ridiculous swerves, the dramatic structure of the whole thing falls into place: It's a story about Ray looking for his father, finding him and finding it within himself to surpass him in the figurative and literal arena of masculinity. No other daily gag cartoonist right now is doing anything as ambitious and intricate; no daily gag cartoonist fighting sudoku and horoscopes and "Beetle Bailey" for its column inches would even have the opportunity.

Shares